Man, I’m Glad We Didn’t Do an ESOP

Introduction:

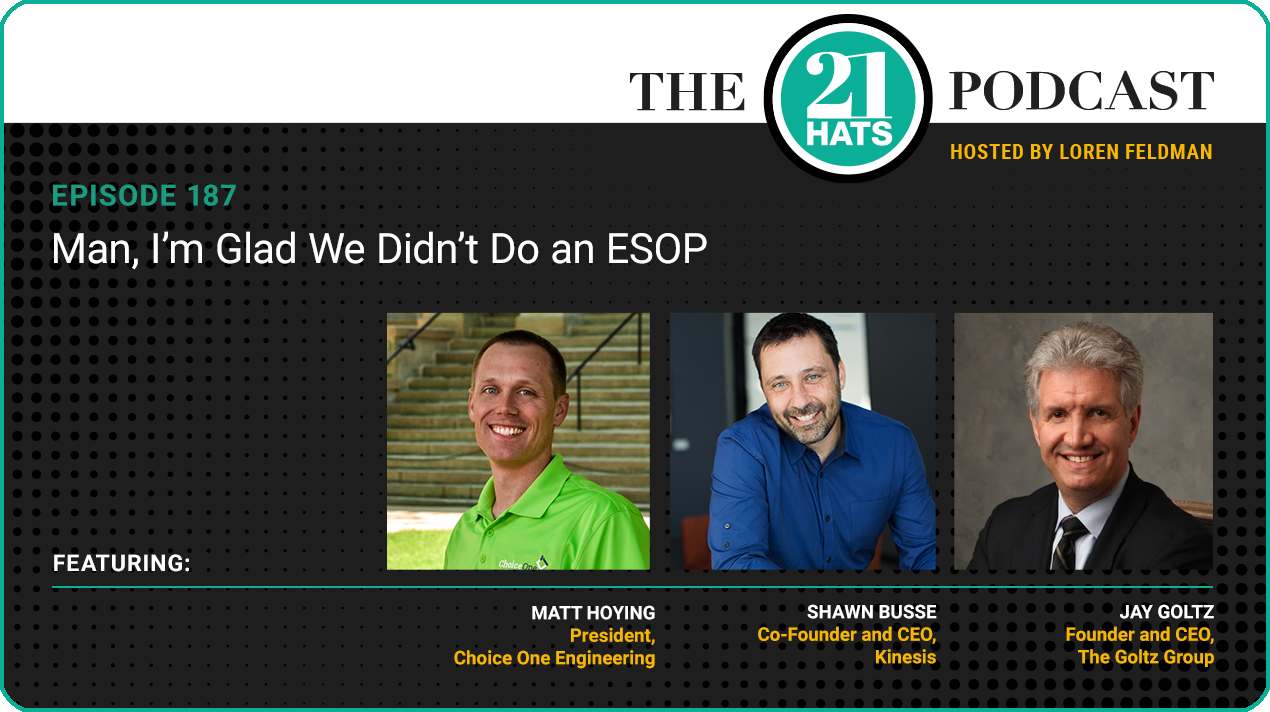

This week, Matt Hoying, president of Choice One Engineering, explains to Shawn Busse and Jay Goltz how he created a DIY employee-ownership plan for his firm. Some 10 years ago, Matt’s predecessor as president tasked him with selecting an ownership structure that would engage employees and help Choice One be as successful as possible. That sent Matt on a mission of discovery in which he researched the pluses and minuses of every structure he could find—including employee stock ownership plans—before ultimately creating his own structure. Matt’s plan doesn’t enjoy the tax advantages of an ESOP, but it’s open even to part-timers, and it requires employees who want to be owners to make a financial investment in the business. In other words, they aren’t given ownership; they have to buy into it. Shawn and Jay quiz Matt on the choices he made and how the plan has worked out.

— Loren Feldman

Guests:

Matt Hoying is president of Choice One Engineering.

Shawn Busse is CEO of Kinesis.

Jay Goltz is CEO of The Goltz Group.

Producer:

Jess Thoubboron is founder of Blank Word.

Full Episode Transcript:

Loren Feldman:

Welcome Shawn, Jay, and our special guest, Matt Hoying. It’s great to have you here, Matt.

Matt Hoying:

Great to be here. Loren. Thank you.

Loren Feldman:

Maybe you could start by telling us what Choice One Engineering does and then giving us a quick overview of how employee ownership works at Choice One.

Matt Hoying:

Choice One Engineering is a professional services company, specifically, civil engineering, surveying, landscape architecture services. We work with public municipalities, as well as private developers, in Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana, primarily.

We have at Choice One an open employee-ownership structure, where generally if you’ve been here for three full calendar years, you have the opportunity to buy into the ownership. We have an internal board of directors that approves that and sets the amount of shares that can be sold. But if you’ve been here for three years, our hope is that you exhibit those characteristics that we’re looking for, as fellow owners. And we have share levels and share structures that we can get into that each employee can buy up to that amount of ownership. And currently, 40 of our 79 employees are owners.

Loren Feldman:

And it’s 100-percent employee owned?

Matt Hoying:

Correct. You must be an employee of Choice One if you want to be an owner.

Jay Goltz:

Wait, tell us how it all started. Where did the founders go? How did that whole thing happen?

Matt Hoying:

Great question, Jay. There were five founders originally at Choice One, and they all were original owners. They had a philosophy in place of: They didn’t want any one owner to own more than 50 percent of the company. So at the time, the president of the company owned 45 percent. And their structure was also an open-ownership structure. I would say it more closely would resemble a key-employee retention structure, where new owners were invited to become owners. They also had to buy into the company, but they were invited to be owners. There was no real clarity or structure around who got invited or when they got invited.

And we currently have three of those five founders still as members of Choice One, so they’re still part owners. Two of them work daily in the business. One of them, the original president of Choice One, is in the process of selling out as he’s reducing his involvement in the company.

Jay Goltz:

So when you say “selling out,” the question is, how does that work? Let’s say he still owns 45 percent. Does he get a check for 45 percent of the appraised value of the business, or how does that work?

Matt Hoying:

We do a yearly valuation. And anyone that would sell or buy shares, we sell them—that transaction’s at that yearly valuation. And we created a step-down, sell-out plan with him that he is selling so many every year. And we’ll write him a check for that number of shares every year.

Jay Goltz:

And he obviously has to pay tax on that money, right?

Matt Hoying:

Correct.

Jay Goltz:

And do you know—and I have no idea—is this what happens at accounting firms, law firms, medical practices? Isn’t this similar? Is this what happens in those kinds of places?

Matt Hoying:

My loose understanding is, yes, it’s similar to that. I have not found one of those places yet that’s been quite as fully inclusive in the ownership. There may be certain principals that are asked. We’ll sell our shares to a certain group of people, but not every employee has the option, whether they’re part-time or full-time, to buy in, which is what our current structure is set up as.

And we have a number of unissued shares. Currently, of our 1,000 available shares that Choice One can sell, we’ve issued 612. So Tony, the original president of Choice One, doesn’t have to sell a share for a new owner to buy a share, if that makes sense.

Shawn Busse:

So you can issue new shares. Are you buying them back through the company? When you said, “we buy them back,” can you clarify that a little bit?

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, the company buys them back, and we essentially just retire that share. So, for example, we just went through this process here at the beginning of the year. Tony sold eight shares back. We’ve retired those eight. But that allows us to sell eight additional shares.

We’re currently limited at that 1,000 number, because that was set up in the original code regulations of the company when they founded Choice One. So every share that he sells back, or anyone sells back, gets retired. And we now have that many more that we can sell to new owners.

Shawn Busse:

When I met you, Matt, I don’t know exactly the size of the firm, but I want to say it was 40 or 50 people. And now you’re twice that size, give or take. So I assume one share is worth considerably more now than it was back then. So, A) is that true? And then, B) does that create any tension, in terms of the cost of buying in?

Matt Hoying:

Yes, it’s true. Our share value has continued to increase. We do a composite, over five years, share values. So we try to smooth out the peaks and valleys. We tried to set a lot of things up in the structure so that it wouldn’t encourage someone to try to game the system, so to speak: “This year looks like a really great year, I’m going to sell out. And then next year when the economy’s looking down or whatever, I may buy-in,” kind of thing. So share value has continued to increase gradually. When I say gradually, 12 to 15 percent a year, year over year.

And then, you asked if that causes tension on people buying in. Yes, it has and does. We’ve done one share split already. Back at the end of 2019, when the price to buy in just seemed unattainable, there’s a kind of a fine line there of: What’s that number? What can someone afford? And what makes sense to ask them to pay to buy in and not?

We’re financially transparent. We have a bonus structure set up through that. And we’ve kind of loosely said that it takes three years, once you’ve been here three years, to buy in. If all you did is save your bonuses over those three years, we want that to be enough to be able to buy a share. There’s no exact science to that. But that’s just kind of loosely what we’ve held internally, as our board of directors, as: What’s that number that’s going to tell us it’s time to split these shares again so they become attainable for people?

Shawn Busse:

Are you comfortable telling us what that number is in dollars?

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, the last time we split them it was when the share price went above $30,000. So we split it. Our philosophy is: We want there to be skin in the game. We want you to have to buy in, and we want there to be some pain, so to speak, of buying in. Part of our hope with this structure is, it’s going to encourage behavior change.

That was one of the things, when I looked at this structure, in changing the structure, I didn’t like about an ESOP. And I’m by no means an ESOP expert, but the thing that I didn’t resonate with the ESOP plan was you just kind of earned ownership for being an employee there. I didn’t feel like that was gonna really encourage behavior change. Where that relates to this conversation is we want to split it at a number that’s not going to make the new price $30,000 and now it’s $15,000. We still want to make that new price something that is enough skin in the game that it’s going to still encourage that behavior change.

Loren Feldman:

Matt, let me stop you there. You just referred to the changes that you made. Your system has evolved through the years. It’s not the same as it was when you first joined the business. Can you take us through that process a little bit? I know you’re president of the company now. You worked your way up. What was the system like when you started at the business? And then how did you come to make those changes?

Matt Hoying:

I started full time in 2007 and was asked to become an owner in 2009. I had no idea why they were asking me. I mean, I was very appreciative of the fact that they were, but there was nothing in writing anywhere that said, ‘This is what you need to do as an employee to become an owner.” And when I was asked to become an owner, there were actually employees who had been here longer than I had that weren’t owners.

And I can specifically remember the place the former president and I went for lunch when he made the offer. And I remember asking him, “What’s this employee going to think about me being an owner, and they’re not an owner?” And, at that time, I was, what, 24? [Laughter] I think I’m still pretty naive today, but I was especially naive then.

Jay Goltz:

Let’s just be clear. He’s also not your father-in-law, right? [Laughter]

Matt Hoying:

Correct. That’s correct.

Jay Goltz:

Yeah, let’s get out of the way, because frequently, that’s what they don’t tell you until you figure it out later.

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, completely unrelated.

Shawn Busse:

It’s like one of those movies where there’s the chosen one.

Matt Hoying:

Shawn, you kind of joke about that, but that was how the structure was set up as, “Hey, there are certain key employees that we don’t want to lose, and this is a way to encourage them to remain committed to Choice One.” And that was something I didn’t understand at the time. And as it got explained to me, that model made sense. And then it made sense of what their plan for my future at Choice One was. So it was very much a tap-you-on-the-shorter invite, kind of open-ownership structure. You still had to be an employee.

There’s a lot of the concepts today that I took from that structure, because I really liked the way they set it up. But in truth—I’m gonna fast forward now to 2014—Choice One went through a pretty transformational year in 2014, where we really sat down and looked at what kind of things are keeping us from being the company we want to be. We have a purpose of providing fulfilling lives for a lifetime. And a lot of what we do runs through that filter. I mean, everything that we do runs through that filter, but we looked at it and said, “What’s not allowing that?”

And two of the things we honed in on are, we talked about wanting a company of people who think, act, and feel like owners. Well, we weren’t fully financially transparent. We were transparent from the standpoint of, if I asked a question, or if anybody asked a question, the president or anyone else would have happily explained it to them. But there was no education around it. There was no, “I don’t know what to ask.”

So we went through in 2014 and created our financial transparency model. And with that, myself and the former president, Tony, had the conversation of, “Well, what else is there?” And I said, “If we want people to think, act, and feel like owners, my opinion is, I think they actually need to be able to be owners.” You know, we can’t just expect that opening the books is going to be everything that we need to change that behavior and get them engaged at that level.

So he, at the time, understood the financials much better than I did. He took on the financial transparency model and said, “I’m gonna set this up.” He gave me the reins to create an ownership structure, to modify the ownership structure in a way that resonated more with what we wanted to be as a company, who we wanted to be as a company. But also, 2014 was really when we announced to the company that Matt would take over for Tony as president. The plan was, that was going to happen in 2021. That actually all moved up.

But Tony looked at it and said, “You know, this ownership structure is going to be something that affects the future Choice One for a long time. Why don’t you focus on this? Because I won’t be around for as long as you will to realize the benefits or the pains of this ownership structure.” So in 2014, I’m 29. I have an engineering degree. I didn’t take a single business class in college.

Jay Goltz:

You didn’t miss much. Trust me. [Laughter] Wait, I have to ask you this question. So what happened when you were 24? Were there not 10 other people who were there for 10 years who said, “What’s going on here? They took the kid and they made him a partner?” Did you get any pushback? You were 24 years old. Weren’t there 30-some-year-olds who were there for 10 years doing the work, who were pissed off about it?

Matt Hoying:

So when I got offered ownership, I was the ninth owner, and we had 20 employees at the time. So at the time, there were only two other people who had been there significantly longer than I had. But because of the previous structure—for anyone who was aware and had some observation skills, which I don’t think I had at that time—you could see the people who were owners were key people in key positions in the organization—either key departments that we wanted to grow and become key people, or currently were key people.

So there were really only about one or two people at the time who probably, in my mind, could have looked at that and said, “Wait, why? Why Matt and not me?” And to this day, I mean, that was something that really stuck with me and why, in 2014 when I was creating this plan, one of the first things that had to happen was clarity around who and how and why you became an owner, and what that process was. It certainly worked out for me, but I didn’t like that there wasn’t a lot of clarity for myself or anyone else.

Loren Feldman:

You were given the assignment of figuring out an ownership structure with very little background in business. How did you approach it? What did you do to prepare yourself? And then how did you proceed?

Matt Hoying:

A lot of my story here at Choice One, I’m very fortunate from the founders and the leaders of the company here who provided me the support and encouragement to go out and do things that I probably wasn’t really ready for—in my mind yet, anyway. But one of the things is, we had a board of advisors, an outside board of advisors, and the president at the time, Tony, invited me into those meetings and said, “Matt, these are three highly intelligent, experienced people. Ask them any questions you have.” And I just started through them and through other contacts that I knew that our business had.

I started asking people: What’s your ownership structure look like? How would you go out and approach it if you were me? I started getting books thrown at me—you know, names of books—and I started getting references, like, “Why don’t you go talk to these people?”

At the NCEO, they had a book that kind of highlighted a lot of different types of ownership structures. I remember reading that one and getting through it, and my head just spinning and saying, “Okay, I don’t understand any of this, I don’t think. So I really need to find somebody who has each one of these types of structures.” Some of them I read and just said, “I don’t like this, This doesn’t make sense.” But the ESOP one kept coming back as prevalent, either through the books or people, other businesses that I knew. And so I started talking to more and more people in those companies.

I was a part of a Vistage group, a key executive Vistage group at the time. So I had a network there as well of people. I could say, “Hey, what’s your ownership structure look like?” So I had a lot of outside resources that I leaned on. I probably read more in that year than I’ve read any other year in my life—not that I’m overly proud about my reading. But that’s where it started, Loren. It’s just a lot of, “Hey, I don’t know anything about this topic. Let’s go find people who do,” whether that was authors or individuals.

And every conversation or every book I read, I would take notes, and there’d be something: “I like this,” or “I don’t like that.” And I had a notebook full of just different pages: “Model this in our structure, don’t model that. This is a great idea. This is a terrible idea.” And I kept coming back to the president of Choice One and saying, “What do you think?” Because he obviously helped create a structure. I kept going back to the board of advisors and saying, “This is what I’m thinking today,” and it went from, “You should be a sole owner company,” to, “You should be an ESOP,” and about anything and everything in between.

And I can still remember, one of the things about the ESOP that I think I understood at the time, was the tax advantage to the owner selling out, the owner looking to transition. I don’t believe that tax advantage was going to be either there at all or as significant, given that there wasn’t an owner who owned the majority of the company. But I felt a responsibility to those owners who had been there longer than me who either were going to be selling out or selling out sooner than I planned to, to make sure that I wasn’t creating a system that was going to be unfair to them. And I kept trying to solve that tax piece. Like, how do I do this with a tax advantage for these guys?

And one of my lunch meetings with a network friend through the Vistage group looked at me and said, “Matt, How many decisions do you guys make at Choice One that are solely based on taxes?” And I said, “I don’t think any.” He said, “So then why are you making taxes such a big deal here?” And that was one of the light bulbs that I remembered saying, “Okay, I can have some freedom to move beyond this piece.”

Now, the plan still had to be approved by all of the current owners. So they were also going to have to be okay with it. But that was the time, that was that light bulb that said, “Okay, I really can just look at Choice One, look at what we want to do, where I want to go with Choice One, and set a structure up that satisfies that purpose of Choice One.”

Jay Goltz:

Okay, so as someone who has spent a lot of time looking into ESOPs, it seems to me that the issue is—there’s no question, I don’t think, that there is a tax advantage to ESOPs, but just correct me if I’m wrong. The reason why you gave up the tax advantage is because, A) you liked the fact that they have to pay money to get into it, which an ESOP isn’t that. You liked the fact that not everybody is going to be invited into it. I assume you liked the fact that you don’t have the government in your place every day, telling you what to do, because there are tons of regulations with ESOPs, because it’s a government-sponsored tax plan. So you don’t have any of that now, I assume, right? Is that true?

Matt Hoying:

That’s correct, Jay. And I mean, you hit the big topics there. But that last one is one of the ones that I look back on and say, “Man, I’m glad we didn’t do an ESOP,” because we’ve changed our plan a couple of times since 2014. You know, not having the control to be able to internally, within our own ownership group, decide what’s best for our structure, was something I just couldn’t get past. Like, I’m gonna have the government telling me what I can and cannot do with our business? That just never resonated with me.

Jay Goltz:

To be fair to the government, I understand why they do what they do. It’s just like a 401(k) plan; they don’t want somebody to be able to take this and manipulate it for the benefit of a few people. So I totally respect that the government’s got their hands in it. Your plan is far more running the business in the most efficient and effective way. And by doing an ESOP, you lose some of the tools to do that. So I totally understand why it was worth giving up the tax advantages for that.

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, and I looked at it as, there are pros and cons, and ours isn’t a perfect system by any means. But what was the way that we could best ensure the future of Choice One? And when I say the future of Choice One, I mean Choice One in the way we want Choice One to be. Could Choice One exist as an ESOP? Yes, absolutely. But there are lots of things we do that an ESOP wouldn’t necessarily encourage or support.

Jay Goltz:

The whole idea of an ESOP [is] you can’t discriminate, which means if you’ve got someone who works for you that turns out to be mediocre, you’ve got to treat them like everyone else. Whereas in another way you can structure it, you can take care of the people who are taking care of the business. I mean, it’s not discrimination. It’s a matter of: I’m going to reward the people that deserve to be rewarded, and the other people I’m not going to worry about. An ESOP is very much regulated that everyone has to be treated the same. And that does tie your hands.

Shawn Busse:

Kind of in defense of ESOPs, I think we’re using a lot of terms like “the government’s in your business.” From what I’ve heard from people who run ESOPs, that’s not the case that the government is up in your business. It’s like my experience has been with managing a 401(k), which is, it’s just very compliance-heavy. And so you’re spending a lot of energy meeting compliance.

And then, also, I think the more important part is you don’t have the ability to be creative, in terms of how you shape and structure things as you learn things down the road, which is what I’m hearing from you, Matt. It’s like, you did something you thought would be right, and then you realized, “Oh, gosh, we’ve got to change it a little bit. And we’ve got to change it a little more, and we’ve got to change it more.” And that’s where I think the ESOP is frustrating, potentially. It’s the lack of creativity that you can have with it.

Jay Goltz:

Well, you just said, it’s a lot of compliance. Many people would define that as having the government in your business.

Shawn Busse:

Eh, I mean, there’s a difference between filling out forms and submitting things—which is how the 401(k) is for me—and literally the government’s looking over your shoulder, which is true in some industries, in some regulated places.

Loren Feldman:

Right, it’s not like they’re reviewing your plans. It’s rules and regulations that you have to follow. Matt, when you were talking about what this would mean for the future of the business, I think you may have been referring to another aspect of ESOPs, which is that you can’t really control what a future generation of owners will do. They would have the option—and maybe even the fiduciary responsibility—to sell the business at some point. Was that a concern?

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, that was probably the last piece of it that really turned me off to the ESOP, was that we wanted to be able to say: We want to operate Choice One as we feel best for Choice One. And if that means continue on forever, or if that means someday, do we sell—I don’t ever see that in the future that I’m involved in Choice One—but my concern was that if a very enticing offer financially was on the table and we were an ESOP, that we would have to consider that. And we like the ability to take those emails or phone calls that come in way too often and just say, “Thanks, but no, thanks.”

Jay Goltz:

Or just hang up.

Matt Hoying:

Right.

Shawn Busse:

He’s from Ohio, Jay. They’re a lot nicer there than you. [Laughter]

Loren Feldman:

Matt, if you did get an offer you wanted to take tomorrow, could you take it? There is a way to sell the business?

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, so in our structure, the president has full authority for every business decision. The internal board of directors, which is made up of a group of the owners, their responsibilities are to approve new ownership, approve the buy-sell transactions of shares, and to elect the president of the company. If we did want to sell, I, as president, could entertain that. I would have to bring that offer to the board of directors and say, “Hey, we have this offer. Here’s the reason I think it’s the right thing to pursue.” And they, as the board, could approve the sale of Choice One.

Jay Goltz:

So you’re not 24 anymore. You’re what, 39 now?

Matt Hoying:

Yup.

Jay Goltz:

And I have to ask, you must have been gifted at something at 24, and maybe at the time you didn’t recognize. Looking back, there must have been a reason why he took you to lunch and made you this offer and had this plan for you. So looking back, what was your skill-set that made you stand out so much that the guy saw you as the heir apparent? Because that’s pretty much what happened. Not not at 29, not at 32, but at 24, which is pretty remarkable. So tell us, what is your gift? [Laughter]

Matt Hoying:

Jay, I’m gonna say what I think it may have been, and it goes back to when I was in high school. I realized that I wanted to help people. So I have a personal vision statement of creating a positive impact on others so we can enjoy life together. And everything I’ve done, whether that’s been in high school sports, or tutoring, or whatever, has been around wanting to enjoy life with people and helping them be successful, sometimes at the expense of my own success. And fortunately, I had a high school math teacher who guided me to not go get a business degree and be one of many trying to make it in the business world. And he recommended I do engineering, because he thought I could handle math and science, and get into project management, which is really people management, and be able to do what I really love doing.

So I think it starts with a realization early on in my life that that’s where I really got my own personal fulfillment from. But I’ve had people along the way who have guided me—my parents, this math teacher, college professors, and then even the people here at Choice One—who encouraged me to continue asking those questions. I was always that person who: I’m going to put my head down, I’m going to do my job as well as I can, and I’m always going to ask what else can I do? What can I do to help?

Hey, I enjoyed being an engineer, but I always had higher aspirations of getting out of engineering, and managing people and helping the employees be successful. So just kind of inherently by that, it requires me to ask questions: “Hey, how can I help you?” For me to feel fulfilled, I need to know how I can help other people. And so I was asking those kinds of questions. And I think that that’s what led—

Jay Goltz:

So, if we had Tony on the show and we asked him, do you think he would give that similar answer?

Matt Hoying:

I think so.

Jay Goltz:

I buy it. I think that makes perfect sense.

Loren Feldman:

Matt, I think you said it was 2014 when you and the founder, Tony, and the president at the time decided to kind of reassess things. Was the business profitable at that point?

Matt Hoying:

Yeah. Even through the ‘08-‘09 timeframe. We’ve always been profitable. It wasn’t anything like that. It was just that continuous strive to want to get better, to learn and improve, continuous improvement. What can we get better? “How can we make Choice One better this year than we were last year?” is really what triggered his thinking of, “Hey, we want to get into this financial transparency model.”

He got turned on to the Great Game of Business. Ownership Thinking by Brad Hams was a book that we read. We’ve always had that mindset. And that comes from Tony, but you know, continuous learning, continuous improvement, continuous absorbing of information, running it through Choice One’s filter to see what would make sense or not make sense and then developing the plan for us. And so yeah, we were profitable then and have been ever since.

Shawn Busse:

How do those time periods compare, Matt? Because I’ve talked to a lot of owners who think that: If I incentivize people with money, they’ll work harder, and we will be more profitable, and they’ll behave in a different way. So I’m curious, what’s been your experience, in terms of changing—I mean, it did sound like half the company was a quote-unquote owner when you took over. So it already had that in its DNA. But how is the profitability compared between those two eras?

Matt Hoying:

Almost the exact same, from a percentage standpoint. Our percentage profitability was in the high 20s, low 30s, then, and we’re still in that same range today.

Shawn Busse:

How about from an equity standpoint? Because a lot of times, you’ll have companies where the people who are the owners realize a lot more benefit than kind of the worker bees. Do you feel like that’s changed? Or do you feel like that’s always been in the DNA as well?

Matt Hoying:

That’s kind of always been consistent in the DNA. One of the things that did change in 2014 is we did put more clarity around it. We used to have a very subjective bonus mindset of, “Hey, this person puts a lot of hours in. They should get a bigger bonus”—not necessarily, “Are they being more productive?” And so we put some parameters around: Here’s numbers. We said a 15-percent return on investment was our goal for ownership. If we achieve that, then that’s when our bonus structure kicks in, and then there’ll be some additional return.

But we really set it up as: Hey, we know there are going to be employees that choose not to buy in. That’s their choice. If people want to invest their money in other places or spend it in other places, that’s their prerogative. They can be an employee of Choice One and not be an owner. So, we didn’t want that to get out of balance to where, “Hey, if I really want to financially be successful, I’ve got to be an owner.” But we also needed to make sure that ownership return on investment would make sense to invest. You know, if you’re getting a 5 percent return on investment for Choice One, but I can put it in the stock market and get 8, then financially, that doesn’t make sense, right?

Shawn Busse:

Yeah, so it sounds like, what I’m hearing is, profits are pretty consistent after the change and going to transparent, open-book management. Seems like satisfaction in the company is very similar. In your mind, what’s changed for the good in making these moves?

Matt Hoying:

So it’s the things that are hard to measure, right? It’s the things that are to say, “Hey, would all of these employees be just as engaged if we didn’t have this structure?” From an employee age, we have a very young company. So I mentioned that 40 of our 79 employees are owners. Well, there are only eight of them who could be owners. So we have that many who just haven’t been here for three years yet.

So it’s an enticing plan, knowing that, “Hey, in three years, I can become an owner.” It’s helped from a recruiting standpoint. It helps from a retention standpoint. And it helps people see—because we do a lot of education around it—here’s how my individual impact returns some actual investment to me. So, the whole what’s-in-it-for-me mindset, we’ve got an ability to draw a direct line there for them. And so now, if we do a good job of hiring, and we’re hiring humble, hungry, smart people who want to be motivated and become better employees for themselves and for the company, there’s encouragement for them to do that. Because there’s either a return today or a future return, when they get to that point.

Loren Feldman:

Matt, were you affected by the great resignation and the labor shortage?

Matt Hoying:

We were affected only in the sense of, it was hard to hire people. We did not lose anybody. We didn’t have any turnover. We didn’t have anyone retiring at that point. But we had some key hires who we were hoping to find much sooner than what we did, who were in that mid- to upper-level experience range. It just took a while to find those people because either the companies that had them were really holding on to them, because they understood that, or there just weren’t that many of them remaining in the workforce.

Loren Feldman:

Did you have to raise your pay as a result?

Matt Hoying:

We did not. We have a philosophy—though the one thing in our financial transparency model that we don’t share is individual salaries—we are going to pay national average, as a base wage. And then our goal with our bonus structure is that you’re going to be in the 75 to 90 percent [range] on those same national surveys, from a total comp standpoint. So it’s an in-it-together collaborative setup there.

Shawn Busse:

Oh, okay, so your salaries then are lower than—well, you said 50 percent. But then, once you add in the profit share, it’s 75 to 90, right? Am I hearing that right?

Matt Hoying:

Yeah.

Shawn Busse:

Okay, so you are asking people, to some degree, to take a little bit of a buy-in, even from the very get-go. Right?

Matt Hoying:

Yeah. So from the very get-go, we’re saying, “Hey, we know you could go get—pick a number—$5,000 more at a competitor,” maybe. We need to be competitive, or we wouldn’t get anybody, but we can then lay out to say, “Here’s what that $5,000 will look like for you at this competitor. They’re gonna give you $2,000 in bonus, and we’re gonna give you $15,000, assuming you help us be successful.”

Jay Goltz:

Help me with this. Here’s my hypothesis as to why they put you in charge. Correct me if I’m wrong. [Laughter] No, I think this makes—just tell me if this is possible. They were all hardcore engineers who were working there. And you, even though you didn’t get a business degree, think like a business person. You’re asking questions, you’re looking for the best ways of doing things, you’re trying to work collaboratively.

Those are all not the same words that go with being a hardcore engineer. So they recognized that you were bringing more modern thinking to the business, and you were thinking like a business person. And up until then, they were really just operating like engineers. Is it possible that’s the reason why you rose to the position you’re in?

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, Jay, I think that’s very possible. I mean, to me, asking questions, showing that interest, and wanting to learn—people who do that, you have some confidence that they’re always going to want to keep doing that and keep improving things. And so—

Jay Goltz:

That’s called a business person. That’s not an engineer.

Loren Feldman:

Do you know of any other companies that have adopted a plan similar or the same as what you guys are doing?

Matt Hoying:

-I know of some companies that I’ve met with that have wanted to talk to me about our structure and that have put in place some aspects of it. I don’t know of any other company that does full, open ownership to any employee. Like, a part-time employee at Choice One can buy in and become an owner.

Jay Goltz:

What about the receptionist who’s been there for 10 years?

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, so we’re a professional engineering surveying company. By the licensing board in the state of Ohio, more than 50 percent of our shares need to be owned by licensed engineers or surveyors. So we have shared level amounts, where a full-time licensed surveyor engineer, landscape architect can own 20 shares. A full-time non-licensed employee can own 10. And then a part-time employee can own six. So anybody who fits any of those categories—so the receptionist, the administrative assistant who’s been here for 13 years—can own 10 shares as a full-time, non-licensed employee.

Jay Goltz:

Do you think that’s the defining difference between your plan and a typical engineering firm?

Matt Hoying:

I think that that’s one. I think that’s one of the pieces, is that everybody across the board—no matter what role they play—can have that sense of pride in ownership. So we’ve got owners across the board in every position in the company wanting to do the best that they can do, because they understand what that means for the success of the company.

Jay Goltz:

I know at most accounting firms—law firms for sure—there are partners, and most people become partners if they’re there a while. In engineering firms, is that the case? Or is it frequently owned by one person and they all work there?

Matt Hoying:

I would say there’s a good mix of both. More of them that I personally know are more in that, “Hey, we’ve got a handful of partners, a small percentage of partners.” The ones that are sole-owned tend to be the 20-and-less-employee-sized firms.

Shawn Busse:

So what’s interesting, Matt, is—at least what I have seen historically with professional services —it’s sort of like the haves and the have-nots. You know, it’s like there’s a small group that’s the partner group, and they really get a lot of benefit. And then there’s everybody else. And those organizations seem to have higher turnover and sort of a greater sense of like two different tribes within the company. That seems to be changing, I’ve noticed. I’m starting to see marketers being promoted to partner, for example, in engineering firms, which would have never happened 10 years ago. It seems like you’re way ahead of the curve and pushing way harder on it than everybody else is.

Loren Feldman:

Matt, is there anything, looking back, that didn’t work out the way you hoped it would, or that you wish you had done differently?

Matt Hoying:

There are several things that we’ve changed in our plan. In 2014, we created this plan, rolled it out. Some of the things that were part of the plan at that time were the president and the CPO could own a percentage of shares, and every other employee was on a maximum number of share level. So, as new owners bought in, their value diluted. But as president, mine wouldn’t, because I could then also buy more shares. We’ve since got rid of that and said, “Hey, if it’s right for everyone else to be on the maximum number of shares, it’s right for the president and our chief production officer to be on a maximum number of shares as well.”

So those share levels, when the plan was created, were set that the president could own 20 percent of the company, the CPO could own 15 percent of the company. And between the two of us, we both only own 35 percent. So if we weren’t leading the company in the right direction, it’s not an unbelievable ask to think that they could remove us from our positions. But it did become apparent to me that: That’s not going to sit right. That didn’t sit right that I could remain at 20 percent while someone who owned 20 shares, or was 5 percent, now owns four and a half percent—and in five years, will only own four. You know, their percentage keeps going down. That was something that we changed.

We also had some allowance for additional shares for what, at the time, we called vice presidents of our other offices. At the time, we had three offices. And fortunately, none of the people who we had labeled in those positions had owned those additional shares when we corrected this. But we ended up closing one of our offices, not because that person wasn’t putting a ton of effort in and doing their best. The market wasn’t what we thought it was maybe going to be. And that kind of made us realize: We shouldn’t use this ownership structure to compensate you for your role that you’re doing every day in the business. We should do that through salary and bonuses. We should do that through your compensation. So we were able to take that out of the plan.

And now, those people don’t have the ability to own additional shares, because they happen to have a skill-set that allows them to communicate better and relate better. Those people in those titles were our business development people, more or less, where they were the ones going out meeting clients, knocking on doors, doing cold-calling, that kind of thing. And when we closed that office—not because of anything Ryan was doing wrong—that was the wake-up call that said: Yeah, we would have taken those shares back. We would have bought those shares back from him. And he couldn’t have done anything differently to be successful. You know, he did everything we asked him to do. And so, that was one thing that we said, “We really shouldn’t use the structure to compensate people for their daily role in the company. We need to do that through compensation, wages, and bonuses.”

Jay Goltz:

Do you have your own parking space?

Matt Hoying:

I do not. [Laughter]

Jay Goltz:

Excellent. Do you have your own bathroom?

Matt Hoying:

Nope.

Jay Goltz:

All right, you’re just a regular guy. Good for you.

Shawn Busse:

Matt, I’m kind of curious about the compensation piece, especially with the two factors of bonus and dividends for share ownership. This is a tension I’ve observed with companies where there becomes more and more owners, is the willingness to pay and invest in things that are not related to driving immediate revenue goes down. So, what I mean by that is, things like innovation, marketing, culture, new-product creation, etc. I’m curious how you manage that, how you keep the company focused on not just the near-term, which is being profitable, but also how do you plan for the future and changing things and creating innovation and focusing on non-billable activities?

Jay Goltz:

Excellent question.

Matt Hoying:

Shawn, honestly, for me, personally, I’m very financially conservative—a lot of people would call me frugal—in my own personal finances. So in an interesting way, I actually feel like I owe it to the ownership group and to Choice One to not be that financially conservative with the company. Because I don’t want to hold their returns back. I don’t want to hold the success of Choice One back because we’re not investing in innovation in those things.

However, I work for an engineering company, right? We have a lot of analytically-minded people who like to see a straight line between cost and return on investment. And so, I spend a lot more time convincing myself, “How am I going to sell this to the group?” Whereas, personally, I could just make a gut decision and say, “This just feels right. Let’s do it.” But I spend a lot more time trying to get that story clarified so that when I let the company know that, “Hey, we’re going to make this investment,” I’ve got the reason that I can lay out for them: This is why I think it’s the right investment. Fortunately, I haven’t made any extremely wrong choices yet. So I’ve built some trust and some leniency from them.

Jay Goltz:

You’ve got some equity.

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, and like I said, it is my nature to be more financially conservative. So I think that that gives them some ease as well. Because, again, I’m working with a bunch of analytical people who also tend to be pretty financially conservative.

Shawn Busse:

Do you worry that that cultivates a culture of: You need a 100-percent win rate? Like, any risk-taking has got to be successful? Because no good risk-taking is 100-percent successful. So I’m curious how you manage that.

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, that certainly builds in. I’m fortunate right now I have a great outside board of advisors group that I’ve intentionally built with people who I know are going to push me in that. And there are several times that they’ll just look at me and say, “Matt, stop thinking about it so much. You’ve just got to do it. You’ve got the finances to afford to lose on one of these. You’re actually holding yourself back by not investing and by not making that decision quicker.” And so I’ve got that kind of in my ear, as well as them saying, “Just take the risk.”

And no doubt, Shawn, there are things that probably we could invest in, we could take some innovation and creativity with and take that leap that we haven’t, that may have paid off. But I’m also fortunate to be in a space where, industry-wide, from a civil engineering standpoint, we’re a pretty low innovation group. So even a slight risk keeps us ahead of the competition.

Shawn Busse:

Okay, I loved your answer there, like how you get pushed yourself. How do you create that within your company, knowing that someday—I know, you’re still young—you’re gonna leave? How do you foster at least some risk-taking in a very conservative industry?

Matt Hoying:

We’ve kind of identified the people on our team here who are those brainstormers, those people who are just dreamers, if you will.

Shawn Busse:

Mini-Matts?

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, I mean, in a way. We really like a lot of what Patrick Lencioni does, and we really latched on to his Working Genius Assessment. I’m kind of known at Choice One as the weirdo, because I’m a “W” and an “I.” I’m a wonder and an inventor. And so, I’m that dreamer. I know who else and the rest of the company knows who else is in that group.

And so we get those groups together on a regular basis and say, “Okay, guys, what are we missing? What can we do?” AI is a big topic everywhere right now, so we’ve put a group of those people together to say, “We need you to stay on top of this for us.” I found people who had that interest who aren’t as driven by the details. And so, they don’t immediately stop something because they can’t see the return on investment. They keep pushing through, saying, “Yeah, let’s test this out.”

Loren Feldman:

Matt, we’re going to have to wrap up, but I want to ask you, based on your own experience and also on your conversations with other owners who have expressed an interest in what you’re doing, have you come to any conclusions about what types of businesses your kind of DIY employee-ownership model would work for, and what types of businesses it would not work for?

Matt Hoying:

I don’t know if it’s the types of businesses as much, Loren, as the cultures within those businesses, because I know manufacturing companies that have cultures that I think this could work really well for. It’s those cultures of continuous improvement, continuous growth, continuous development. When they focus on people development and wanting the employees to be better, and the employees themselves buy into that—which, to me, is a sign that that’s truly part of their culture then and not just something on the wall—it’s when the employees want to continue to develop and make the company better because of pride, satisfaction, fulfillment, whatever that may be, that’s where I think a model like this works. Whenever you can have an open ownership, and you don’t have one owner questioning, “Why is this other person an owner?”

You know that they’re going to do their part in their own role to make the company as successful as possible. That’s where this works. If you’ve got an environment where there’s a lot of disparity, and the culture is, let’s say, a hierarchy-type culture, where I don’t trust that that person on the front line cares as much about the company as I do, I don’t think this ownership structure is right in that environment.

Loren Feldman:

Jay, what do you take away from this?

Jay Goltz:

Well, A) I think if you wrote a book, it would be called, Running an Engineering Firm Like a Business, because I think that’s what you’ve done. I think it’s worked well for you, because you’ve a bunch of professionals who are engineers. I don’t know that it would work in a typical manufacturing company, where you’ve got some people making $20 an hour. I mean, I don’t know. For me, personally, it doesn’t really apply to my kind of company, but I totally can see where it’s worked well for you.

Loren Feldman:

Why is that, Jay?

Jay Goltz:

Because I’ve got 130 employees, some of which are $20-an-hour employees. It’s just different, for lots of reasons. You’ve got a bunch of college-educated professional engineers who have a different mindset than somebody who makes $20 an hour. I’m not saying it wouldn’t work. I’m just going: It’s not necessarily gonna. As Matt just said, it’s different.

Shawn Busse:

Do you have any problem with, say, non-engineers understanding this? Or, you know, administrative folks?

Matt Hoying:

No. We have field surveyors that have a high school education level, and one of my favorite stories of this employee ownership taking effect, actually, comes from one of those guys going above and beyond, because they were an owner.

Jay Goltz:

What’s that person’s salary?

Matt Hoying:

Well, now they’re above $20. At the time, they were below $20 an hour. That’s a position that starts around $17 an hour for us.

Jay Goltz:

And do some of those buy in?

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, all of them that are eligible have.

Jay Goltz:

I’m surprised that they had the money. If they’re making $20 an hour, they’re putting food on the table. I’m surprised that they had the income to be able to come up with the 10, 20, $30,000 to buy in.

Shawn Busse:

The cost of living is a lot lower in rural Ohio, too. Is that fair?

Matt Hoying:

That’s a fair statement. I think it comes down a lot to the education we do on, “Here’s what this means.” It’s an investment.

Loren Feldman:

Do people borrow money to pay for entry?

Matt Hoying:

Not from the company, but there are people who I do know who have loans from banks, or from family.

Jay Goltz:

Wow. I got the family. I’m surprised at banks.

Shawn Busse:

I mean, the returns are amazing. And you’ve got, what? 20 years of those kinds of returns or more?

Jay Goltz:

Just to be clear, when you say the bank lent them money, I have to believe they had some collateral to back up the loan. Yes?

Matt Hoying:

The bank that Choice One banks with has offered zero-collateral loans to them.

Jay Goltz:

Oh, okay.

Shawn Busse:

Wow. That is incredible!

Jay Goltz:

That makes sense. They know your company. You should always mention that. That’s valuable and interesting.

Matt Hoying:

Yeah, that’s one of the reasons we bank with them. They’re a local bank and do things like that.

Shawn Busse:

That’s so cool.

Loren Feldman:

All right, my thanks to Matt Hoying, Shawn Busse, and Jay Goltz—and to our sponsor, the Great Game of Business, which helps businesses use an open-book management system to build healthier companies. You can learn more at greatgame.com. Thanks, everybody.