Should I Open My Books to My Employees?

Introduction:

This week, we have something a little different—a remarkable conversation that focuses on the merits of open-book management. The conversation features six business owners—three of whom are open-book skeptics (you may recognize their names) and three of whom are true believers. It’s not a fight, it’s not an argument, it’s not even a debate. Instead, it’s a lively exchange—owner to owner—about management strategies, what works, and what doesn’t.

My guess is that this conversation may dissuade some listeners who were intrigued by the notion of opening their books. And I think that’s okay. Open-book isn’t for everybody. On the other hand, I suspect many listeners will have their interest confirmed, but if they choose to proceed, they will do so with their eyes open. Most important, I believe that even listeners who have no interest in opening their books will be fascinated by this intimate discussion of how six smart owners run their businesses.

First, some background: The father of open-book management is Jack Stack who led a group of factory workers who took over a Springfield, Missouri manufacturing plant some 40 years ago. Stack introduced the concept of revealing the company’s finances and training employees to understand them so that they can better understand what drives the business. The idea is to get employees more engaged.

All of this has certainly worked for Stack’s company, which is now known as SRC and where he is still CEO. SRC has become something of a mini-conglomerate, with dozens of businesses and more than $600 million in annual revenue. One of the businesses created by Stack and SRC is known as The Great Game of Business, which promotes open-book management and holds an annual conference, The Gathering of Games, which attracts hundreds of businesses from around the world.

The conversation you are about to listen to was hosted last year by The Great Game of Business and I think they deserve tremendous credit for allowing us to have such an honest and hype-free discussion. I’ve been looking for an opportunity to publish it, and this seems as good a time as any.

I started the conversation by asking each of the three skeptics why exactly they’re skeptical.

— Loren Feldman

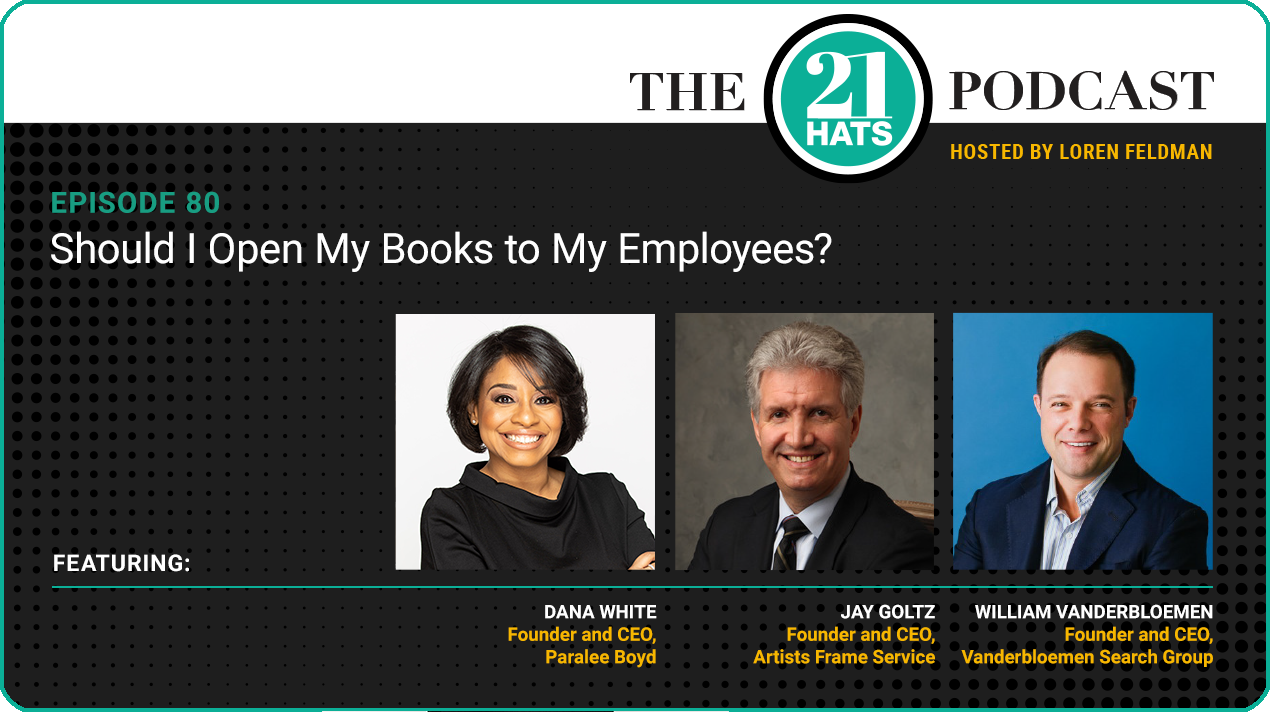

Guests:

Dana White is founder and CEO of Paralee Boyd hair salons.

Jay Goltz is founder and CEO of Artists Frame Service and Jayson Home.

William Vanderbloemen is founder and CEO of Vanderbloemen Search Group.

Michael Kiolbassa is CEO of Kiolbassa Smoked Meats.

Chris McKee is managing partner of Venturity.

Bob Schwartz is CEO of SuperSuds.

Producer:

Jess Thoubboron is founder of Blank Word Productions.

Full Episode Transcript:

Loren Feldman:

I want to start by asking each of our skeptics what their biggest concern is—what would really what’s keeping them from opening their books—because they’ve all thought about it a little bit. Dana, let me start with you. What’s your biggest concern?

Dana White:

So I have started, or I have tried, an open-book management system with my staff. At the time, pre-COVID, I had a staff of 19 people, and it has been successful with my operations manager. However, what I’ve learned in sharing it, I’ve learned that it’s not necessarily a fit for everyone, depending on the industry you’re in. When you look at your staff, the culture might be there with your team. But if you’re working with people who have some life challenges or aren’t there for the business mindset, it’s really hard to open up your balance sheet and your profit and loss and explain it. They’ll see it and say, “Oh, well, you’re making this. Why aren’t you paying me more?”

And no matter how many ways we try to explain it to them, we found that opening our books can cause some resentment and some questioning as to how we’re running the business. And even though we were open, we found that it didn’t really help the morale of the company. It was fine to do it amongst managers. But when it went to our day-to-day operations with people, it wound up not helping as much as we had hoped.

Loren Feldman:

I suspect that’s a concern that a lot of people who come to this share. William, how about you? What’s your biggest concern?

William Vanderbloemen:

Well, maybe I just have a fear of the unknown, Loren. There are a lot of smart people who do open-book, and they seem to be doing really well. You’ve got good speakers today. So I don’t know that I have the answer for everyone. But I think that right now I have the best answer for our situation. Some of that may be baggage that I’m carrying from having worked in a form of open-book in my prior life.

In my prior career, I was actually senior pastor of fairly good-sized churches. And in the type of church that we were, everything was open-book, including the compensation of every pastor to a congregational vote. Every year, every line item, how much on books, how much on vacation, how much time. And while it sounds like a transparent thing that “the stockholders should get to vote on,” it made it very hard to keep people engaged. Where we were supposed to be a cause-based business, you’d find people being envious. And you’d like to think that pastors don’t act that way, but they do. And not only was it open-book for our company, but it was open-book for the world. Everything was on the internet, so it was pretty shocking to work in that system. And so maybe I’m just dealing with scar tissue from what I felt to be overly transparent.

Loren Feldman:

Well, it’s not like you’re just imagining these concerns. You have some experience in this area. Give us an example of what went wrong.

William Vanderbloemen:

When we’d try and hire people, they could see—”Well, why are you paying the older guy, who’s been here longer but isn’t doing nearly as much as I am, more than what I’m getting?” So the decision-making had to be driven by the dollar. And as now in my current career as an owner, I make decisions for the good of the business that don’t always make sense for the immediate P&L. And if everyone in my company is looking at everything on the P&L, and saying, “Why in the world are we doing that? That doesn’t make sense.” Now, I’ve got a bunch of people who are acting like owners when they’re not.

The freshest example: We do searches for all kinds of faith-based teams, so we help churches find their pastors. That’s one of the things we do. Recently, there was a pastor—he’s about 35 years old, four small kids. He’d just given a sermon on being the Good Samaritan, helping the guy on the side of the road. A couple of nights later, he’s driving down the side of the road and sees a car pulled over. He stops to help them, is trying to repair their car, gets hit by a truck. He ends up dying. It’s a tiny little church. They would never be able to afford help finding a new pastor, and they’re decimated. And I said, “We’re doing this search, and we’re not charging a nickel.” And if everything were open-book, I guarantee you, I’d have somebody saying, “But what about the P&L?” It’s those kinds of—as an owner—the ability to still make highly agile decisions.

The currency of our company is our cause. It’s why people come to work here. It’s why they’re engaged. It’s why they say it’s a fun place to be, a meaningful, significant place to be. Not all businesses are based on a cause for a higher good. Totally understand that. But for us, I read through all of the advantages of open-book: higher employee engagement, more fun in the office, more frontline with customers. All of that for us goes back to our cause and not to our dollar bottom line. So maybe it’s baggage from my past. Maybe it’s that we’re cause-based and not so dollars-based. But for us right now, it’s just not the decision I want to make.

Loren Feldman:

I think part of what I’m hearing from you, William, is you’re doing okay with what you’re doing. Opening the books seems like a big, risky adventure that you don’t have a compelling reason to try right now.

William Vanderbloemen:

And Loren, I should say, it also seems like a one-way street.

Loren Feldman:

Meaning…

William Vanderbloemen:

There’s no going back once you open them, unless you want to start over with your staff. And it’s interesting, I was reading, preparing for this: One of the big, competitive advantages of open-book is that you’re going to be forced to keep your books so well that when investors want to come and look at your company as a potential purchase, they’re gonna say, “Oh, everything’s kept so well. And that’s usually the big stop on purchases.” Well, that’s fine and well. But investors may not want to buy an open-book company. And I don’t know how they undo that once they buy it.

Loren Feldman:

Jay Goltz, you’ve known Jack Stack for years. You’ve actually sent people to The Gathering of Games. You’ve given this real thought, but you’ve never been able to pull the trigger—or gotten to the point where you wanted to pull the trigger, I should say. Tell us what stopped you.

Jay Goltz:

Oh, I did send three people down there, and I have an unusual business in that I’ve got everything from 40 factory workers who make $15, $16, $17 an hour. I have managers making $60,000, $80,000, $100,000 a year. I’ve got sales people making $50,000. So I’ve got a big range of salaries and job responsibilities. I don’t need my employees to act like owners. My employees are responsible. I almost never find them doing anything that I wouldn’t be doing. I have employees who are fully engaged. They look out for the best interests of the company. And they’re really solid “work with” kind of employees, so I don’t have an issue with that.

But I have played around with the open-book theories, because it does make sense on many levels, and I’m sure it works very well for many companies. But the problem I had with it is—2008, let’s talk about. My industry: All of my businesses are home-furnishing-related. We took a 30 percent hit and my guys went down to The Gathering of Games probably right after that, or a few years after that. And they came back and said, “Half the people there said they hadn’t shown a profit for five years. And there was no sharing of any money.”

How demoralizing. And I had been living through that myself. I decided I was going to start doing a bonus plan based upon profits. I used to just give it per year: You got 25 bucks a year. If you were there 20 years, you got a $500 bonus. If you were there two years, you got $50. So I abandoned that and went to some sort of my own half-assed game of figuring out profits and handing it out. And every year, I dreaded going to the last meeting of the year and going, “Listen, guys, we really didn’t make the money we thought we were gonna make. We can’t give you a bonus this year,” and I dreaded it. And then finally a few years ago, I decided to go back to my old method. And I have to tell you, it was this huge albatross off of me. They get their bonus at the end of the year based on how long they’ve been there. Everybody’s happy.

I’ve just decided—at the moment, and I’m still open to it, unless someone can convince me otherwise—that there are three things: You can either not do it. Okay, it’s working fine. I could do it badly. That would be worse than anything. Or I could do it in the best possible way, and I haven’t figured out how to get the metrics to work for that. And William, I’m right there with every single thing you said, including making decisions. If I want to buy new trucks because I don’t want my trucks to be driving around the city of Chicago all rusted out, the employees will go, “Wait a second. That truck was perfectly good. We could have driven that for another year.” I didn’t get into business to answer to what everybody thinks they should be doing in the business.

I don’t really want to leave myself open to having 110 people telling me, “Oh, no, you shouldn’t have spent money on that.”

Loren Feldman:

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. We’ve got three people now on the hook to answer a lot of questions. Michael Kiolbassa, let me start with you. There’s so much to cover—and feel free to go anywhere you want to go—but I would ask you to start with this question: How do you deal with the transparency issue? I know this was a concern of yours early on—that if people looked at what the numbers really were, that they would run out the door and find a job somewhere else. How have you dealt with people knowing what the real numbers are inside the business?

Michael Kiolbassa:

Well, thank you, Loren, for asking me to be on this. And listening to Dana and William and Jay talk, I’m nodding my head in agreement more than I thought. It’s a risky deal. And really, the reason we opened our books was, we were growing our business. We’re a sausage manufacturer. It was 2013, we had just launched this program called Values-Based Leadership, which is a leadership development program that really puts your mission and your vision and your core values at the center of everything you do.

And we’re starting to grow really fast. We’d been growing around 15 percent a year, and we started growing 25 percent a year. And that may not sound like a big difference, but it really stretched all of our systems and processes. And I had two conversations going on in our business—and we were profitable, don’t get me wrong. We were making money. But when you’re growing 25 percent a year, you need to be making the margin necessary to finance that growth. And if you don’t, you’re going to have to leverage your balance sheet to finance that growth.

So I had two conversations going on with my senior managers at this time. One was, “Hey, Michael, we need to start building a new plant to keep up with our growth.” And the one going on in my head was, “Hey, we need to start building cash.” And I had to bridge that gap somehow, and so I reached out to Verne Harnish—some of you all may know Verne—and he led me to The Great Game of Business, and we opened up our books.

It was a very scary moment for me. I mean, transparency is not easy. But I felt like it was the right thing to do, and I really needed to teach people how the business made money and why cash flow—forget profit—is so important. And in the moment, I opened up the books, we had at the time 150 employees. I brought in the top 30 managers including my senior team, and I said, “Okay, here’s reality, guys. This is what we’re making. This is how much cash we’re generating every year. And it’s not enough to keep up with our growth. We’ve got to figure out how to do this.” And I went from being a boss who was acting like I was letting them make decisions—but I was really making them all—to giving them the information and becoming a coach to allow them to allow them to learn how the business makes money and generates cash.

That was seven or eight years ago. We’d gone through a lot of peaks and valleys during that period. Opening up your books is not a panacea. It’s a commitment. But we’ve grown the business 5X over the last eight years, but I guess the most important part of that is we’ve grown the bottom line about 10X. And so that wouldn’t have happened if I didn’t have the alignment within my organization over how we make money and generate cash. It’s been a very powerful program for us.

I add, William, to your point: I think we’re a little bit unique in The Great Game of Business community. I don’t know that we’re totally unique, but I think that having the values-based culture and the foundation of that really accelerated the adoption of The Great Game principles without having a lot of the drama associated with it. We do not share individual salaries. We are beginning to share the balance sheet and teach the balance sheet to our team members. That’s a very complex element of this. We’ve been doing that for about a year now, and so you do have to explain dividends and distributions and things like that.

Loren Feldman:

Michael, do you feel like you have people looking over your shoulder? Do they challenge you on—like Jay’s example—buying a truck, or something like that?

Michael Kiolbassa:

Well, I would say they challenge me in a good way. I’ll tell you a quick story. This was about a year after we adopted The Great Game of Business. We had an HR person who had come to me and said, “I need help.” And I said, “Do you want help above you or below you?” And she said, “No, I’d rather have someone come in above me to help.” And so I went out on a search to find somebody. I found a very capable person to help. And I brought it to my senior team, and we had vetted this person out. We were getting ready to pull the trigger on bringing her on, and I said to my senior team, “Tell me what the guys on the floor are saying about this, bringing in so-and-so. And my VP of engineering said, “Do you really want to know?” And I said, “Yeah, I really want to know.” And he said, “The guys in the maintenance room want to know why we’re adding overhead when we’re not making our budget number yet.” I said, “Wow, that’s pretty good. Pretty good question. It sounds like my father.”

Anyway, we pulled back on it. We did not hire. And we lost the person who had come to me and said she needed some help. But we managed through it, and it was a very positive and powerful experience. Because it told me that the guys on—at least in the maintenance room—really understood how important it is to generate EBITDA and cash flow.

Jay Goltz:

I have to say, what you’ve described is not necessarily open-book management. The fact that the guys in the machine room decided that you shouldn’t hire the—what? Maybe you would have gotten sued for not keeping track. Maybe you haven’t seen the rest of that movie yet. Maybe you think you came out ahead, but maybe you really did need an HR person. What you’ve just told me is you have delegated running the company to the guys in the machine room. And then I don’t see what that has to do with open-book management. They told you don’t spend the money on something that they really don’t have the facilities to understand—what the HR person really does—and the lawsuits, and the legal responsibilities on all of that. So that’s not helping me with saying, “Oh, this is a good idea.”

Michael Kiolbassa:

Well, I appreciate it, Jay. But really, what it did is it challenged our own systems and processes for bringing on additional headcount. It challenged me to think about the HR role and what we really needed. Over my history, I’ve been very quick to bring in people, and they just challenged it. I actually give them a lot of credit for challenging me.

A friend of mine, who is one of the most successful business people I’ve ever been around, said—and I believe in this—“The secret to being successful is surrounding yourself with really smart people. And then tell them where you want to go, and then get out of the way.” And so, I do not consider myself the smartest guy in the room in our company by any stretch of the imagination.

Jay Goltz:

Did the people in the machine room ask you what the responsibilities of that job were, so they understood what they were nixing? Did they say to you, “Explain to us why you think you need to”—did they go through that conversation with you?

Michael Kiolbassa:

Well, we explained that the reason we were hiring is that one HR person felt overwhelmed, and they needed help. And their response was, “Well, let’s get rid of her and go find somebody that can take her job.”

Jay Goltz:

Did you do that?

Michael Kiolbassa:

That’s what we ended up doing, rather than adding a headcount.

Loren Feldman:

Chris McKee, I want to bring you into this. You have an accounting firm. You have accountants who, presumably, without open-book management, had a pretty good feel for how the company was going. How did the transparency change things for you with an accounting firm?

Chris McKee:

I’ll say, a lot of the things that the other folks have said really resonate. I actually became aware of The Great Game of Business probably five years before we implemented it. And I was thinking to myself, “Yeah, that can’t work for us.”

Loren Feldman:

Why? What were you thinking?

Chris McKee:

Like Michael, I was worried that they would be shocked at how little money we were making. And we were doing fine financially, but we were mostly marginally profitable. And there was a lot of opportunity for improvement there. We felt as we grew as an organization, most of what we were trying to do to improve profitability and improve performance was to run around and tell people, “Well, you need to do this, you need to do that.” And that was just becoming not at all scalable, and it wasn’t having an impact. And for us, our gross margin and profitability didn’t really change in those years leading up to implementing The Great Game of Business.

So I finally—it was kind of after trying everything else, we went with opening the books completely, and The Great Game of Business. We brought in a coach and took our team through their process, and it helped a ton with educating people and preparing them for being aware of: What does profit really mean? Some of the things that Michael talked about: What are these dividends? And we have found that they, after going through that process, really understand that we’ve got to be profitable as a company, to invest in the future and to protect their jobs. It actually brought them a real comfort level—at least I think, I’m not going to speak for my team—in knowing that we were profitable and that they could have an impact on that profitability.

And I just haven’t seen a lot of the issues. I feel like I do have 40 people running the company now, where they’re really having an impact on the things that they do every day. How can we be more efficient and effective—efficient with our processes, and therefore, leading to more profitability, and effective, in terms of creating a better experience for our clients, and therefore retaining our clients and helping us grow as a company?

Those are some of the things that kind of came out of it for me, but I resisted for a long time for some of those same reasons. Once I kind of got past that, it was a, “We’ve tried everything else.” And since then, it really has made a huge impact on—similar to what Michael talked about—on profitability. I don’t feel like I’ve got 40 bosses. I feel like I’ve got 45 fellow leaders really helping me run the company, and it’s just been a huge weight off of our shoulders from that perspective.

Loren Feldman:

Do your people know what everybody makes?

Chris McKee:

No, we don’t reveal salaries. They know broadly. We have categories of salaries, like the COGS salaries that are related to client delivery, and then sales and marketing salaries, G&A salaries, so very broad categories. And frankly, we are a little mindful when we’re adding G&A salaries about the transparency of that, and it really causes us to ask ourselves, “If I were an average employee in this organization, how would this appear to me?” I think it makes us think about it more mindfully, and make better decisions and also explain those decisions to the team, and give them a context for those decisions that we’re making.

So far, in three years, I think it’s been very collaborative. I think we’ve had some decision points in the company where having that sort of thought process and even some of those conversations has held us a little more accountable to some of the decisions that we’re making and some we move forward with and some we pull back with, like Michael talked about. And I think that’s even brought more credibility to the open book process for us, is that process of really listening to the team.

Jay Goltz:

How much does the average person make that works for you there?

Chris McKee:

That’s a great question. It’s obviously going to be more than in your situation,

Jay Goltz:

Like multiple times more. Is it $80,000?

Chris McKee:

I don’t know if it’s quite that high. I think it’s probably more in the 60’s, but sure, it’s going to be a little bit more. And hey, look, I’m gonna say we have an advantage in that we are an accounting firm. People have some financial literacy. But some of my folks are on the call, so they’re gonna probably be upset from me telling the story on them.

But just before we showed them the P&L, we asked the team, “How much money do you think we’re making, top line and bottom line—revenue, and then how much of that is making it to the bottom line, like net income?” And my team is accountants, and they’re very conversant with financials. And at the time, we were a roughly $4.5 million dollar company, and we had probably 35 folks, and we had guesses anywhere from revenue of $500,000 to $50 million and net income of $250,000 to $25 million. There was a thought that I was potentially making maybe $25 million a year, and so even for accountants, opening the books really gave them much more of a perspective. They see clients’ financials every day, but everyone thought that 50 percent of revenue was dropping to the bottom line, whether it was $500,000 or $15 million. So I think the education process has got to occur regardless, and I think people are capable of learning processes.

Loren Feldman:

Chris, that’s a great point. Jack Stack always talks about how, when people say to him, “I don’t want people in the company to know how much we’re making,” he says, “Believe me, they already assume you’re making way more than you really are.” And if that was true at an accounting firm, you can imagine it being true elsewhere.

Bob’s Schwartz, I want to get to you and SuperSuds. You have a particularly interesting situation. You have a Wall Street background. You bought a chain of laundromats. It’s not an obvious target for open-book management, I don’t think. You have multiple locations, employees who aren’t paid a lot of money. What attracted you to it?

Bob Schwartz:

Thanks for including our company in this. I really appreciate it. The background, real quick, was a Wall Street background, years ago. I came from a financial background. I understood numbers. I was the deal guy, an investment banker. But what I learned out of frustration and ignorance was, there’s a big difference between investing in a business and operating a business. And at the end of the day, after 20-some years of different stuff, I got frustrated with the operating side. I didn’t consider myself a great operator, a great manager necessarily. I thought I was a pretty good deal person. But like I said, there’s a big difference.

And so, I think a couple things that I wanted to bring out to everybody here was, one: I think open-book management is just one piece of it. Sharing the numbers is just a piece of The Great Game. You could say it’s the foundation, but there’s so much more to it than just sharing numbers. You know, there’s the engagement. There are other components to The Great Game, in addition to just sharing numbers—from huddles, people trust you, our employees trust each other. It’s not easy. It’s not a panacea. It takes a lot of hard work. But our performance has been remarkable since we’ve done this, and you don’t have to share their salaries. Like Chris has said, you can create open-book any way you want to meet the needs of the company. So you don’t have to share what you make personally, but you’re still getting the same effect. You’re getting buy-in, you’re getting trust, you’re getting alignment.

Loren Feldman:

Let me stop you there. Don’t your employees have some sense of how much money you’re taking out of the business, if the books are open?

Bob Schwartz:

Yeah, they have some sense, but as a result, there’s a level of trust I believe that they have with what we’re doing. At the end of the day, people want to be part of a team. They want to be included. They want to be heard. They want to be felt. And at the end of the day, they’re not pointing fingers at the owner and saying, “Oh, look at him.” They may have been, prior to doing this. But now that we’ve opened it up… My CFO knows, basically, obviously, what I make, but you don’t have to bring it down to the hourly wage person what I’m bringing home to get the same effect of open-book management. I don’t think that makes sense.

Loren Feldman:

And why do you think opening the books improved the performance of the company? What difference did it make?

Bob Schwartz:

I’ll give you simple examples. I mean, we have somewhere between 25 and 30 stores, depending upon what we’re doing, or selling, or building. It’s a big CapEx business. Utilities are a big component of it. So we have all these locations, all these stores. And it sounds crazy, but just at the very simple level, our store staff or store team members are responsible for the P&L at each store, and a big driver of that is utilities. So prior to this, the doors were left open, water—I mean, it just goes on and on. The utility costs were through the roof. And then we started saying, “Okay, here’s the deal. Here’s our P&L, this store. Bonuses are tied to profitability.” All of a sudden, it’s like the light switch comes on, and it’s amazing what people will do to tighten down the hatches and to drive profit. I mean, it’s just human nature. I don’t know how else to say it. They’re shutting off running water valves, they’re closing the doors, they’re not running the AC all the time. It goes on and on and on. And you know, after three or four years, it really adds up.

Loren Feldman:

Bob, you’re, as you said, a deal guy. You bought SuperSuds with the idea that you would probably flip it. I wonder if you would address William’s concern about what it would mean if you were looking to sell the business at some point, having gone down the open-book road.

Bob Schwartz:

Yeah, that’s a good question. That was one of my problems, is I got into business, and I enjoy running it now, but I didn’t at first. But now I’m like, “Okay, how do I get out of this thing? And what’s my exit strategy?”

Everybody’s different. Everybody’s personal story is different. In my case, I’ve made the decision that I want to continue to operate the business. My plan is to create an ESOP out of it. We’ll be the first in the entire industry to do it, as far as I know. So there’s a way for me to exit to an ESOP, which I was not even aware of until I got into this whole The Great Game thing. So it’s created an exit strategy for me that I was not aware of.

At the end of the day, if you’re going to sell it to a financial buyer, they care about what your profit or loss is, what kind of return you’re getting. And if it’s open-book, and it’s driving numbers, all the better, I think. They’re gonna buy what you’re selling, and if you’re selling an open-book, that’s fine. Now, you don’t have to create an open-book. Like, Jay, if you’re happy running the business the way you’re running it… I mean, for me, it was a personal decision to create a better operating structure at the end of the day. That’s my decision. I just needed a better way to operate my business.

Jay Goltz:

I mean, some of what I’ve heard is, “We had bad management. We had employees that weren’t doing what they were supposed to be doing. We have managers that had no clue how much money we were making—and that this fixed all that.” Okay, well, to me, that’s a false choice. There’s good management. There’s bad management. There’s The Great Game of Business, which is a form of good management. I don’t know that one needs to jump to The Great Game of Business to start practicing good management.

Bob, in your case, why is the air conditioning on? And why is the faucet on? And why is the door wide open? To me, that’s management. Like, why did it take having to put The Great Game of Business to have a manager who knows to shut the door, turn off the air conditioning, and turn off the water and the other thousand things that managers are supposed to be doing? I’ve found that you can get people to act like responsible managers without doing this, and that there’s some downsides to doing this. At the moment—and I’m still open to it, believe it or not—I look at some of the downsides, and I say to myself, “It’s just not worth all the energy.”

I would just look at someone with a $10 million business and say, “If somebody is pulling $600,000 out of the business, how do you either hide that in the financials—if you’re truly open-book—and they see management and they see that number?” Someone’s gonna go, “Oh, that’s okay. He deserves 600 grand. He put all the risk into it. He’s been working at it for 30 years. And when he loses money…” I just don’t know that I want to open myself up to having to explain why the owner of a business should be making a return on investment and what it should be.

Dana White:

Even though we don’t practice open-book management with the entire staff, everybody on my staff knows what everybody makes. We have that open-book. And they know because I’m young and the business is young, Dana’s not pulling out anything. But I believe when the time comes, and it’s time for me to draw a salary from my business, I know not to disclose that. Just like I know not to pull up to the salon in the Cadillac. You pull up in the Pontiac.

And that’s having a culture. But I just think it’s interesting how there’s open-book management, but we don’t really talk about what everybody makes, versus we tried to practice it. It really hurt the business, as far as how people interact with each other. But everybody knows what everybody makes. Just an interesting flip on it.

Chris McKee:

I’d like to jump in and address Jay’s point about bad management versus good management. Look, we have mostly the same people who we had before we implemented The Great Game of Business. Going open-book management, whether it’s through The Great Game of Business or some other methodology, has made them better managers, better leaders, better team members, because now they can see a lot more how the business all fits together and works, and how they can have an impact. And quite frankly, they’re better at servicing our clients as well, because the things that our team has learned in learning how our business works teaches them how to talk with our clients about how their businesses work, because we do the accounting for our clients. For us, we’ve got all the same people. This has really helped us educate them and take them to the next level. They were already really smart, effective people, but it’s an additional tool that’s helped them grow.

Bob Schwartz:

Yeah, Chris, I would second that. By this education of the financials, we’ve created some managers who have become really good, who maybe weren’t as financially sophisticated as they were prior, to the point now we’re creating some other vertical businesses within SuperSuds—unrelated stuff—that they’re going to manage, which they honestly probably weren’t prepared to do five years ago. I mean, look at how many businesses SRC has. What are they, 50 or 60?

Jay Goltz:

You know, the point is, there’s a big bandwidth. I’m doing some of that. I’m probably doing half of what The Great Game of Business is about.

Loren Feldman:

Wait a second, Jay.

Jay Goltz:

A third? A quarter? Some part. I’m not suggesting keep everyone in the dark. It’s when it gets down to tying their compensation to how the company’s doing. So my question is, and maybe some of you don’t have businesses that ever have bad times, for those of you that have had periods where the company just didn’t make money for two, three, four, or five years, do you feel it added a different level of stress to yourself or to your employees?

Loren Feldman:

Michael, maybe you could address this. To what extent do your employees profit more when the company does better and how big an issue is it if the company has a tough time?

Michael Kiolbassa:

Well, they’ve got a direct line of sight to whether the company is doing well or not, which kind of demystifies the whole process. I want to jump back to something that maybe, I think William brought it up, or maybe it was Jay. We’re a branded sausage business, and so when you’re building a brand, you’re making investments—not necessarily translating into profits right away. Whether it’s going into a new market, whether it’s introducing a new product line, whether it’s beginning a relationship with a new customer, I mean, that takes investment. And for years, we had a real disconnect in our business, because we were bonusing off of Ebitda.

What I was trying to do is really build brand value, which has two different dynamics, and it really caused a lot of stress in the organization, and it wasn’t an easy conversation. I had to spend a lot of time coaching people on the importance of the brand value. But we have made—with the addition of a really great CFO who’s come in and helped as we’ve grown the business—we’ve been able to really gel around EBITDA and get to a performance standard for a brand. We just got through paying almost a million dollars out in bonuses to our team members for the past six months. And I cannot tell you the excitement. They knew what was coming because they saw the financials every month, but you can’t imagine the excitement.

And going back to Bob’s comment around trust, the transparency of The Great Game of Business—and The Great Game of Business is simply an operating system that uses open-book management as part of thr tool. That’s very important to understand. It’s an operating system that we recommitted to actually back in 2017. And since we’ve recommitted to it, it’s been an amazing, amazing journey. But the transparency of The Great Game of Business magnified the trust in our organization, which unleashed creativity in every area of our business, created much more creativity that me or even my whole senior team could unleash. And that, to me, is the secret sauce that makes businesses successful: the creativity.

Loren Feldman:

To the point of your employees challenging your decisions, you had a tough decision last year where you walked away from a very big client of yours, which might have been a tough decision to explain. Can you tell us about that?

Michael Kiolbassa:

Talk about a gut-wrenching decision. We just spent about $4 million adding capacity to our business. We added a new production line and increased our capacity about 50 percent. Right after we did that, our third biggest customer came to us and said, “Hey, that branded product that you make that we sell, we want to convert it to a private label product once you make it.” And I said, “We really don’t do private label.” And the buyer said, “Well, if you don’t do it, I’m going to get somebody else to do it.” So I had to go to our team. “What do you want to do here? Let’s talk about this, because, again, I’m not the smartest guy in the room here. I want to get everybody involved in this.”

We quickly understood that although this guy was our third biggest customer and had 20 percent of our business, it was our lowest gross profit margin customer. And we really didn’t need to replace the top line dollars associated with this. We had to replace the gross profit associated with this. And so that became a much different conversation over how we could replace the gross profit associated with this, and it made the conversation and the decision much easier for us to make. As a result of that, we still walked away. We had to replace that business, but it was an educated—we call it “holding hands” in our business. It was a chance for us to hold hands on a strategy to actually become more profitable than we would have had we maybe not framed the conversation in terms of gross profit.

Jay Goltz:

So how many people were in that meeting that you discussed that with? The whole company?

Michael Kiolbassa:

No, no, no. Probably, initially, it was the top seven team members I call my “senior team.” But then we took that conversation down to our mid-level managers, which are about five people, and explained it to them and got their input. And they all agreed, “Let’s go chase after their lost gross profit.”

Jay Goltz:

I do the exact same thing. That’s what I’m struggling with. That’s what any good company would do. They talk to their key people and have a conversation. I don’t know what that has to do with having The Great Game of Business down to the guy in the loading dock. Any good company would have that conversation. So I don’t think this is all or nothing. I don’t think this is The Great Game of Business, or you don’t tell anybody anything. I think there’s somewhere in between. I just want to ask you the million dollar bonus: What percentage of profit was that?

Michael Kiolbassa:

It was about 15 percent.

Jay Goltz:

Okay.

Chris McKee:

And Jay, you have those conversations, but when you’ve opened the books and really educated them about the business—I think, is part of Michael’s point—the conversation was a different conversation because they understood the business a little bit better. Rather than, “Well, gosh, we just need to keep every customer at all costs.” If they don’t really have that perspective on the financials, the feedback that you get is not as informed because they just don’t have the context. And I think that’s where I think it’s part of Michael’s point, is you just get better decisioning all the way down to the loading dock. It’s not just about asking them, it’s about giving them the tools to actually help you.

Loren Feldman:

I wanted to go back to you, William. When you gave the example of the church that you wanted to help out without charging them because their pastor had died being a good samaritan, I have a hard time believing that your employees would struggle with that. I think—I know—you’ve hired people who are looking for a larger cause. I think they probably would have been okay with that. So I don’t think that’s the real reason you’ve shied away from doing this. I’m curious if you’re hearing anything here that’s making you think about it at all?

William Vanderbloemen:

Yeah, so Loren, we’re all in sales here, right? Everyone on this call? So I picked the easiest example.

Loren Feldman:

Okay.

William Vanderbloemen:

But the underlying principle is the same. It was a question I’d like to raise with Michael’s example. It’s a fascinating decision you had to go through, Michael. Props to you for getting through it, and it makes me want to go buy your sausage over at H-E-B—unless they were the customer.

Michael Kiolbassa:

They were not the customer.

William Vanderbloemen:

So props to you. So a two-layered question. One’s actually just selfish. I’m curious to know, of that senior leadership table that you have, Michael—you’re a family-run business—were any of those people related to you in any way?

Michael Kiolbassa:

No, none of them were related.

William Vanderbloemen:

Okay, that clears a lot up, because we work with a lot of families. We’re a family business. So where does that come into everybody knowing what’s going on? And that’s a whole different onion to peel.

To me, I’m really not the smartest guy on this call. I am truly a recovering pastor who’s just trying to figure out how to run a business. And what has served me well over the years are some gut-level decisions that really didn’t make sense at the time. And to me—that sounds like a non-data-driven reason to not be open-book—but I’ve got a friend who is a pastor of a very large church. And he was talking about his compensation and retirement, and he said to me, “William, I don’t think they pay me to preach anymore.” And I said, “What do you mean, Mark?” And he said, “Preaching’s fine. I like doing it. It’s kind of for free, but where I earn my salary, I get paid to make about four decisions a year that no one else wants to make.”

And you can be as open as you want, but sometimes the owner makes a call that’s going to go against the grain of what everyone else thinks or believes. Now, maybe you’re in a purely data-driven business. Maybe you’re more mature as a business. I mean, Michael, your business has been around a long time. Way to go for being open, what, almost 70 years, or a little more? That’s a long time, so you’ve got a lot of data. We’re young. Things shift. Things change.

We had to decide, during the pandemic: What are we going to do? Churches and schools have been closed. That’s put a little bit of a damper on our business. So we’ve had to make some pretty hard decisions, some of which we’ve done very similarly to what I’ve heard the panelists that are pro-open-book do. But at the end of the day, the decision is with the people who have the name on the door.

And Loren, I’m just not getting more convinced. If anything, I’m more convinced of my position. I think what I’m learning is open-book doesn’t have to be telling everybody what everybody makes. That’s a big deal. But what I’m also learning is the things I’m hearing—which are super good practices in the companies using open-book—are things we’re doing anyway. But we’re driving our conversations by our values.

I do have people who have worked their fingers to the bone during a time when we’ve been down in business. And for me to say, “We’re going to take on a search,” which is a big, tall order—we sell big widgets, not little ones—”and nobody’s going to make anything but you still need to work just as hard.” Like, that’s just not going to go well, even if it’s the Good Samaritan getting killed. Now, I did pick the easiest decision, so valid call on me. But whether it’s that decision or another, there are, through the history of our company, a number of times where we’ve done the thing that’s counterintuitive, and it’s been our best decision.

Loren Feldman:

I hear you.

Jay Goltz:

Did you see the question here? “I’d be interested to hear the panel’s take on sharing specific financial performance metrics versus totally open-book management. Can you get the benefit without the downside?” I believe so. That’s kind of my whole point.

William Vanderbloemen:

I totally agree.

Jay Goltz:

I can’t think of one time in 42 years where I had my key people sit around a table, they gave me their opinion, and I said, “Thanks for the input, but here’s what we’re doing. It’s my business.” I totally am doing all that stuff. It’s the connecting it to income that I choke on, because I think that’s where it just adds a whole new layer of potential problems that I don’t want to accept.

Loren Feldman:

Chris McKee, you not only have a window into your own business, but you’re an accountant and you talk to lots of other businesses. Maybe you could deal with that question that Jay just read off the screen.

Chris McKee:

Yeah, we had considered just opening the books, and in fact, for a number of years, considered just opening it down to gross margin. And that is our critical number in The Great Game of Business parlance, which is what our bonus is based off of. And I think that’s something that’s very doable, so you could open up down to a certain level. Gross margin for us is sort of the thing that everyone has the ability to impact the most in all the little decisions they make every day. And that’s really the piece that’s changed the most for us.

I would say it’s a process that everybody’s got to go through when they’re implementing open-book management, however they decide to do it. And that piece of it has been really impactful. We decided to go in and open all the way down to the bottom line, because we really wanted people to understand the context in which we were operating and why it was important, perhaps, to generate more gross margin, beyond the theory that there’s a lot of other bills that you’ve got to pay. But I don’t think it’s an absolute requirement.

I’d say the only difference when we used to just open the books down to gross margin, we were bonusing people off the gross margin that they were generating. We were organized in little teams and we were bonusing based on gross margin by team. And we were finding some teams that were doing great, and some teams that were doing not so great. And in the end, it didn’t move the needle for the company at all. We were paying out bonuses to people who were already doing well and not to people who needed help and that kind of thing. Moving into The Great Game of Business methodology sort of pulled that all together, and we all began working together much more as a team.

But I do think there could be situations where you open the books down to a certain point and you design your bonus structure to create movement around that number. You don’t have to necessarily open all the way to the bottom line and show owner’s compensation. And if that’s a big piece of the heartburn, I think there is an opportunity to consider that.

William Vanderbloemen:

If you’re a sole-owned business, and you show all the way down to your bottom line, how do you not show owner’s compensation?

Chris McKee 1:01:07

Yeah, no, I agree. I agree. But you know, I think there’s an education process, again, that goes on with that money doesn’t all just sort of go into my pocket, if you will. And we do have several other owners within the company, but I’m still the majority owner. But they understand. We’ve educated them. We have to finance receivables. I don’t get to just take all that money out every day, at the end of the day, and write myself a big check. There are cash flow demands of the business. And maybe my team understands that a little better, because they are accountants—or it was easier for them to figure out. But I know by going through that education process, they understand why a business needs to show a profit at the end of the day. And sometimes it’s a substantial profit, because there are going to be times, difficult times, where you’ve got to be able to dig into that profit as well.

William Vanderbloemen:

That’s super well said, Chris. One of the things that my wife and I have talked about a number of times, and we’ve talked with a lot of other entrepreneurs. And one thing that keeps coming up is, if we were a publicly traded company, and we had a, call it a small number—100,000 shares out there with 500 owners—and there was a rock bottom line that was getting split among shareholders, I don’t think employees would have a problem with that. But when it’s one shareholder, they do.

And that’s what I keep hearing over and over, whether it’s with a $1 billion business or a $10 million: If there is only one stockholder, and you’re running the business at healthy margins that would be appealing to somebody like Bob, if he were coming to do a deal—well, I’m not going to buy that business, if they’re only making 1 percent a year. But I’m assuming healthy margins and one owner, I don’t know how every business can say open-book is good categorically. And I think it might be great for—gosh, Bob is thinking about ESOP. This makes total sense. I mean, wow, that’s perfect. For us, and where we are in our life as a company, it just doesn’t.

Jay Goltz:

Here’s the question: open-book management. Everyone’s given their opinion. I’d like to know officially from someone who works for The Great Game of Business. Open-book management, to me, has always meant open-book management—all the numbers are out there. And now I’m told, “Well, no, not necessarily.” So which is it? Is it the employees? Is it the owner’s salary? Or is it not? Because I could take an $800,000 salary and leave $100,000 profit and go, “Yeah, we’re barely making money.” So I’d like a clarification on that.

Loren Feldman:

Jay, I think I can answer that. No one has ever said—associated with The Great Game of Business—that salaries have to be included. Chris McKee, am I right about that?

Chris McKee 1:03:59

We don’t. If somebody from The Great Game of Business does want to jump in and sort of verify: It’s tailored to every company’s needs. You go through an implementation process, and you and the team help design how open book management is going to work for your company.

Donna Petiford 1:04:39

We have a saying: “Adapt versus adopt The Great Game of Business.”

Jay Goltz:

Nice, yes.

Loren Feldman:

Thank you, Donna. Bob Schwartz, I wanted to ask you maybe to address a point William made earlier about what it’s like doing this through a down period. I don’t actually know for sure, but I’m guessing this has been a tough year for a chain of laundromats. I assume you had to be closed for a while. What has it been like for you with your employees?

Bob Schwartz:

Yeah, I was gonna address that. You know, when times are tough is when you want to be doing this at the end of the day. Come March, we were sweating it, because we’re in five different states, and every state had a different view as to what’s considered an essential business. And so fortunately, we were considered essential, which means we stayed open. But what happened to us—and I didn’t bring it up—I had many employees come to me and say, “Do we need to take a pay cut? I’m willing to take a pay cut. Defer my bonus.” Okay, that would never have happened. Never have happened. It would always have been me making a tough decision. And now the tables are turned, because people generally understand how we operate, and they have a level of trust that we’re going to do the right thing by them. And they want to stay in this in the long-term. Can you do it without The Great Game? I’m sure you can. It’s just, it was a better operating system for me, to run it this way. And especially when times are tough, you want to be transparent to people. They’ll come to the right decision, I believe, at the end of the day, if you’re open with them.

Loren Feldman:

Michael, does it work for you in tough times?

Michael Kiolbassa:

Yeah, I mean, when we walked away from that 20 percent of our business volume, after we’d just added 50 percent capacity, we were able to really engage everybody throughout the organization on: Wow do we reduce costs to get through this? We didn’t replace that gross profit right away. It took time. What Bob says is exactly, exactly right.

And I don’t want to sound like this is the only way to make it work. I mean, it sounds like Jay and William have great operating systems, that they can produce the same impact. It’s just, it works for our culture. It works for the way I want to run the business. We have aspirations, Bob, as well as you do, for an ESOP down the road, so it’s setting us up for that option. I don’t want anyone to walk away thinking that this is the only way to do it. There’s a hell of a lot of successful companies that don’t do open-book management, but for our culture, for the way I want to run the business, it’s really been very, very effective for us.

Loren Feldman:

Dana?

Dana White:

You know, you can create a great culture. You can have all of that. But I think, as a business owner, you have to also know your staff, and you have to know what they’re dealing with. My staff doesn’t want to look at the P&L and figure out—or not even figure out, but be told—how they’re contributing to it or how not. They want to know: How much are you paying me? When am I getting it? And is there a bonus? How much is that that you’re giving me? That’s it.

During COVID, I would be in these Zooms, and everybody’s like, “Oh, we’re doing a dueling Piano Bar happy hour for our staff.” And it’s not that I work with bad people, but I understand the issues that are facing the women who I’m working with. Single mother of three kids: she’s like, “Okay, like, so does this mean I’m not getting my check on Friday so I can pay for this? Or what does this mean?” I’m not working with people who want to be business owners. And so I’m listening to everybody and just thinking, “Wow, I just come from a very different culture.”

Loren Feldman:

That’s a great comment, Dana. Let me take that to Bob. Bob, you don’t operate a hair salon, but I suspect your employees—before open-book—were not thinking about what it would be like to be a business owner, either. Could you address Dana’s concerns?

Bob Schwartz:

Yeah, it’s a process. I mean, what we found is it’s a process. It takes time. Adoption is not easy. It takes work. What we’ve done is, we share all the numbers. We share the company P&L. People don’t know that Mary makes this, and Sally makes this, and yada yada yada. You don’t get into that minutiae. We do share the P&Ls every month, every quarter, but what really matters to employees at the stores is, like you said, “What am I getting paid? Can I get paid? And what is my bonus?”

You can create a scoreboard. In our case, every store has a very simple scoreboard that we’ve worked with GGOB to develop that matters to us. And it’s basically six or seven items. That’s what they’re looking at every day. It drives the number. But it’s not into the minutiae, the P&L. It’s very simple. But again, it’s the line of sight that ultimately drives the bottom line of the company. And they share in that bonus, simple as that.

Dana White:

We had our key performance indicators for our staff, and we give them bonuses based on that. But we found that when we shared the balance sheet and the profit & loss with anybody that wasn’t a manager, the mindset wasn’t, “Wow, I want to make this better.” It’s: “Why aren’t you giving me more?” They just were not connecting. The culture at Paralee Boyd is these women are extremely committed to healthy and quality hair care for women who have been overlooked—being committed to timeliness, being committed to healthy hair care.

Michael Kiolbassa:

Dana, this is really important to me. You mentioned the socio-economic—

Dana White:

Mm, the cultural.

Michael Kiolbassa:

We talk about the great divide, the haves and have-nots. This is my personal opinion. You’re free to agree or disagree, but in my opinion, the free enterprise system is the most powerful engine for social justice the world has ever seen. The Horatio Alger stories, from the immigrants coming over to this country and starting with nothing and creating something because of their entrepreneurial resourcefulness. This is what made this country great, and I think we are at risk of losing that, because we’re unwilling to grab the narrative on the power of the free market to lift people up. And part of that is our unwillingness to be transparent about how business operates and why profit is necessary and really teach.

When we opened up the books—and keep in mind, for over half of my workforce, their primary language is Spanish. And when we opened up the books and we started teaching them about—okay, I’ll never forget. We did our first open-book budget, and I got to the bottom line. And I said, “Okay, guys, what do you want to do with this money? What do we want to do with this money?” I mean, clearly we’re in a business that if I take everything out every year, we’re not going to be around very long. So we had to reinvest this money, and they started talking about these items that we needed to invest in, whether it was equipment or whatever. And I said, “Wait a second, I forgot to tell you something. I said 40 percent of that”—this is several years ago—”goes to the government in taxes.”

And they couldn’t believe that 40 percent of that money that they were working very hard to get was going to go to the government. And I’m not trying to make a political statement here. I really think that you bring up a really powerful element of why it’s important for us—if we don’t adopt The Great Game of Business, and there’s lots of different ways—we at least need to initiate a conversation around the importance of the free market in this world, and especially in this country, because I think we are in danger of losing the narrative here.

Loren Feldman:

Guys, I hate to do it. But I think I have to end this conversation. My thanks to Dana White of Paralee Boyd, Jay Goltz of Artists Frame Service and Jayson Home, William Vanderbloemen of Vanderbloemen Search Group, Michael Kiolbassa of Kiolbassa Smoked Meats, Chris McKee of Venturity, and Bob Schwartz of SuperSuds. I do think we may have changed some lives today. I think people learned some things here—either by convincing some people to give this a shot or by convincing them to run in the other direction, which is a service as well. We all know it’s not right for everyone. Thank you all for taking the time today. I really appreciate it.