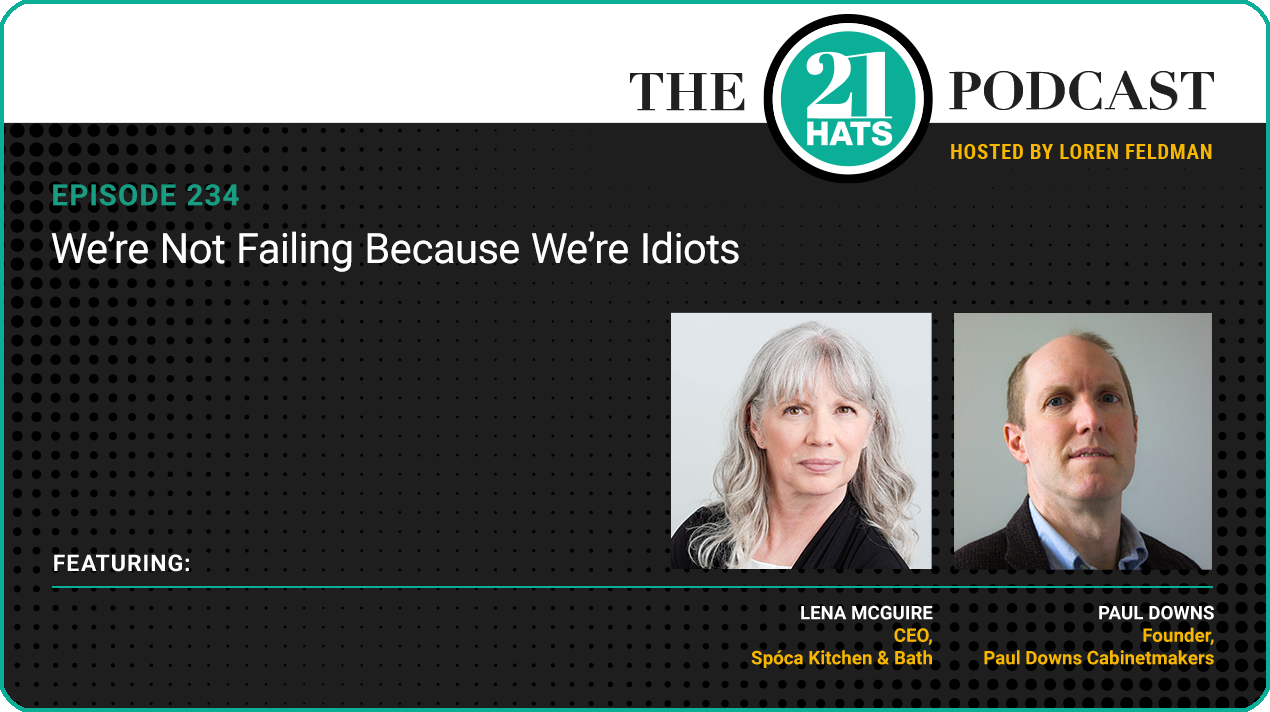

We’re Not Failing Because We’re Idiots

Introduction:

This week, Paul Downs tells Lena McGuire that, because his business has not picked up, he has had to lay off two employees. Paul explains how he chose which employees to let go, including to what extent he considered who has just had a kid and who just put a down payment on a house. We also talk about whether Paul should start experimenting with different ways to attract business or whether he should continue to do what’s worked in the past and try to ride it out. And then there’s this: Paul has managed to do what so many owners strive to do, which is to take himself out of the day-to-day operation of his business. But what does that mean when there’s very little business coming in? How should he be spending his time now? Plus: Lena and Paul respond to a small business subreddit post from a business owner who quit a comfortable job to pursue the idea he just couldn’t get out of his head. Now, he vacillates between thinking his business is going to be huge and thinking he’s made the dumbest mistake of his life, and he wants to know if anyone else has experienced that kind of doubt. I think we know the answer to that one.

— Loren Feldman

Guests:

Paul Downs is CEO of Paul Downs Cabinetmakers.

Lena McGuire is CEO of Spóca Kitchen & Bath.

Producer:

Jess Thoubboron is founder of Blank Word.

Full Episode Transcript:

Loren Feldman:

Welcome, Paul and Lena. It’s great to have you here. I want to start with you, Paul. Last time we spoke, you told us that, after having your best year ever in 2024, your phone had kind of stopped ringing, and you were burning through your backlog and realizing that you were probably going to have to lay off some people. Did that, in fact, have to happen?

Paul Downs:

Yes, it did. It was very distressing: distressing for me, even more distressing for those laid off. I laid off two out of 26, and one took a voluntary leave of absence. She had to help care for her parents overseas, and so she was happy to take a couple months off. But it’s terrible to have to disassemble a team that has been carefully put together and trained over the course of years, and now we’ve got to go back. I’ve been in business a long time, and I’m pretty clear on what number of people I need in the building to do what amount of work, and I just don’t see this heading in the right direction for us. I’m very worried that I may have to make more drastic cuts. So, there we are.

Loren Feldman:

Sorry to hear that.

Paul Downs:

Yeah, it sucks.

Loren Feldman:

You told us that your expectation was that these people did not see it coming and were going to be blindsided by it. Is that, in fact, what happened?

Paul Downs:

Yes. I mean, it’s not like I had said, “Hey, next week I’m laying everybody off.” I just got up in front of the whole company and gave them the numbers and said, “This is what has to happen so that the company itself can survive.” Were they blindsided? I think that one was, but he also has a side business that was starting to heat up, so he was not so bothered by it.

The other one may or may not have been. We had had some performance issues earlier in the year, and had sort of been like, “You know, you’d better straighten your game up.” So given that there were three people in his department, and it was a department that needed to be cut because we just don’t have enough work for it. I don’t think he was completely surprised. It doesn’t mean he was happy about it. He begged me to get rid of one of the other guys instead. And I was like, “No, I’m not doing that.”

But anyway, it’s a bad day for everybody involved. But, I mean, they qualify for unemployment, so I told them to go file for unemployment. And Jay’s warnings notwithstanding about the cost of unemployment—the long-term cost of unemployment is high—but the cost of inaction is much higher. I’ve learned the hard way that if you hang on too long to a cost structure that’s suited to a different level of business than you’re actually achieving, you’re gonna cause a lot more harm if the company runs out of cash because of that.

So, not my happiest day, but the rest of the company seemed to understand the need for it. I haven’t noticed any huge problems with morale or anything this week. And the sales staff is very clear on what they need to be doing, which is closing deals. But we’re only working with the people who show up. And I honestly can’t think of anything that we’ve done to poison the well. There have been other times when I was having a bad time and looked around and saw nobody else was, and it turned out it was something that I was doing. And I just don’t see it this time, because we’re basically doing all the same things that led us to success over the last 10 years. And last year, all these same plans and approaches to the market resulted in enormous success.

So what is it? What’s different? Well, I think we all know what’s different, and I feel that the confidence level in the economy is probably dropping fast. I’ve talked to a couple of other business owners, and they all feel the same thing. Nobody really knows what’s going to happen next, and that’s a bad thing for businesses that rely on people feeling good about spending money in order to succeed.

Loren Feldman:

Paul, have you just not attracted new work, or have you actually had people cancel projects or stop projects that they were close to signing up for?

Paul Downs:

There’s a number of projects that are sort of hanging out there, and that should always be true. It’s always true that you’ve got projects in all kinds of states of stasis, that we have a lot of clients who are sitting on opportunities for pretty long periods of time before they pull the trigger. But there’s a healthy mix, and there’s an unhealthy mix. And at the moment, the projects that we’ve got hanging out there are all, at root, funded by the federal government, and that makes me extremely nervous.

And we have not seen as many projects that were sort of in the control of just a person and their money—not so many of those on the books at the moment. And then we had one pretty substantial project that was going to go to Canada. We hadn’t sold it, but they were making all the noises. And then Trump pulled out his tariff things, and they did a complete 180 and said, “No, sorry, given the uncertainty, we’re going to find a Canadian company to do this.”

Loren Feldman:

Wait, do you think it was economics, or do you think they were angry with the U.S. and wanted to support a Canadian business?

Paul Downs:

Probably both. So, that’s where I’m at right now. And since our last conversation, we did close one reasonably-sized deal, so we went from complete disaster territory to just bad territory. But I don’t feel a lot of momentum going through February, and we’ve got work at the moment through more or less the end of March. So I’ve got about six weeks to get something going.

Lena McGuire:

And at that point, you have to reevaluate if the numbers are working for you?

Paul Downs:

Oh, I’ll be reevaluating before then, because you’ve got to slow down. You can’t be carrying the costs of the $6 million-a-year factory to the point where you run out of work. I just can’t do that. And it’s just, it’s just terrible. I wouldn’t want to get rid of any of my people. They’re all good. And then if they go somewhere, how easy is it going to be to get them back? It’s a situation I’ve been in before, and I try to tell myself it’s not quite as bad as the worst situation I’ve been in, but it’s not great. And I’m not feeling great about it.

Loren Feldman:

Paul, how did the other employees react to your having to do layoffs?

Paul Downs:

Well, as I said, I have not had any pushback. I think that that’s one of the things that, over the years, the way I’ve managed the company is to try to keep people always informed about what I think is going on with the business. And I keep enough data about what’s normal to be able to see when we deviate from that, and I keep the company informed of that. And so I think that, when presented with the facts, they were just like, “Well, that’s what it is.”

And there’s two things you can do when you’re in trouble: You can try to get everybody to feel a little bit of pain, or you can concentrate the pain on a couple of people and get rid of them. And the people who remain much prefer that you got rid of a few people rather than, say, cutting everybody’s pay or hours. So, that’s just human nature.

Loren Feldman:

Are you sure about that?

Paul Downs:

Absolutely.

Loren Feldman:

Because I’ve heard a lot of examples of companies where employees have come forward and said, “This is a tough time. We want to try to protect as many people as we can. We’re willing to take pay cuts to save jobs.”

Paul Downs:

I’ve never had anybody volunteer to do that, although I have done it, and when I did it, it was accepted. I didn’t have as many defections as I thought I would, but people are very unhappy about it. And what they’re mostly interested in is when we can restore the pay levels. But that doesn’t actually solve the fundamental problem, which is, you’ve got a machine that’s just gobbling the work too fast—faster than it’s coming in. Because if you keep everybody around, even if you paid them nothing, eventually you’d run out of work. I mean, you’d run out of work pretty quick. So there has to be a balance between what’s coming in the door and what your capacity is. And yeah, I mean, that’s really what it comes down to.

We have a product that requires human hands in a certain quantity. And if we have X amount of work, we have X amount of hands. And if you have half X, you’ve really got to have half X hands. So we need to maintain a backlog in order to actually operate. You can’t be, “Hey, sell it today, build it tomorrow.” It just doesn’t work that way. There has to be probably at least a six-week backlog to actually operate the company. And if it goes below that, it’s very, very bad.

So the good news is that I’ve got the data that tells me what I think is likely to happen. I’m not being blindsided by this on the day-to-day level—like, okay, I’m blindsided on the, “Wow, I can’t believe that six months ago, I was telling people to go away if they weren’t willing to pay our highest prices we could think of.” But you know, okay, I know what changed. And so now it’s just a new normal, and I have to do what I have to do.

Loren Feldman:

Lena, are you looking forward to having employees?

Lena McGuire:

Absolutely not. This is scary, but I know it’s necessary. So these are learning experiences. I’m interested to figure out: How do you determine which people and which method? Like you said you could spread it across all the people, or just cut a couple. And I definitely agree with what he says about cutting one or two people and keeping that morale up, and also keeping the business going, the machinery of the business going.

But as far as, which of those people are you going to let go, Paul, did you have any idea that somebody wanted to take a leave of absence, that somebody else had a side gig going on so it wasn’t going to be as detrimental to them? Or was that something you discovered after you had made your decision who it was that you were gonna cut?

Paul Downs:

No, I take it into account. I mean, I knew that the guy with the side gig had the side gig. He told me that when he was hired, and I was like, “Great.” It didn’t bother me. He also has a business building and maintaining guitars, which is a tough business in itself, but he’s got enough work lined up that he was having trouble doing it, because he was working for me, that it was a fairly painless landing for him.

Now, I’m always pretty aware of the situations of my employees. And this guy, a couple of weeks ago, had just put down a down payment on a house, and so that was something that was in my mind. But it turned out—I talked to him last week—that the house just absolutely failed inspection, so he backed out of the deal, and that made it easier for me to be like, “Okay, you’re on the list.”

The other guy, I’m not as familiar with the ins and outs of his financial situation, but his wife is working, and he’s never really seemed to be in a situation where he needed every penny. But now, once we’re through with those two, it becomes a lot less obvious who to do next, because I am aware of their situations. I do know who just bought a house and who just had a kid and who did this and who did that. That absolutely enters into my thinking about, “Okay, how likely am I to choose this person, or to choose that person?” But we’re at a point now where all the decisions are bad. There’s no easy way to get through this. But I think it is important that a boss understands what people’s situations are.

Lena McGuire:

And how are you mitigating it so that you’re not losing sleep at night knowing that you made the best choice you can? That’s something I worry about, because as the owner, you have awesome responsibility.

Paul Downs:

I’m sorry, the phrase “not losing sleep at night,”—if that scares you, you should never own a business. [Laughter]

Lena McGuire:

No, I know it’s going to happen, but how do you mitigate it so that you can actually balance that out? Because, like I said, the responsibility of being a business owner, you have all these people. If you hire an employee, you have responsibilities. And a lot of it, you take it personally, I think. How are you doing it so that you can say, “Okay, this is good. It’s business, not personal”? But you know these employees.

Paul Downs:

Well, a lot of it comes down to having numbers to back up your decisions. And so I could demonstrate very clearly to the company that: Here’s where we were, and this is what we did, and this is what happened. And here’s where we are now, and this is what we have to do.

And it’s not like we’ve never been in this situation before. Last year, we did $6 million. This year, let’s say $3.5 million. Well, I was at $3.5 million in 2013 or whatever it was. And so I’m quite familiar with how many people are required to do that work and what it looks like. So if the decision is the only decision, it’s easier to make your peace with it.

Lena McGuire:

That makes a lot of sense. So what we have here is, you have years of experience. You’ve been in these situations. It’s almost cyclical, where I’m new with this. I haven’t made any hires. So, obviously, I haven’t had to fire anybody, let anybody go, or make any changes like that.

Paul Downs:

Well, I think that one of the things that points out is the value of just keeping records, even from day one, when you start, of keeping records about certain things that a lot of people don’t keep any records about. For instance, I track every call that comes in the business. So I have some idea of how many a normal year consists of—what’s the relationship between the number of people calling and the sales?

And having done that for a long time now, I have a very good sense of: Okay, this is what’s likely to happen, given these conditions, these starting conditions. It all starts with us, with people picking up the phone or sending us an email and saying, “Hey, I’m interested in buying a table.” And if you have X number—last year, we had about 1,275 of those—great. That yielded this. And now, at this point, I’m looking at maybe two thirds of that, and so, that’s likely to yield this. And I have to then match all my costs to whatever’s happening there.

Now, one other thing that makes it easier for me to make a decision—it doesn’t help me sleep at night—of course, I immediately stopped paying myself. So now, this year, I’m likely to make $0, because that’s just what has to happen. Now, I will say one other thing about leadership, which is that one of the things that people look for in leaders is, first of all, are they rational? Second of all, are they confident? And so that even if you’re making a tough decision, if it’s a rational decision, and you’re like: I’m confident this is the right way to go. This is the best way to go. This is what we have to do. And if anybody’s got any other ideas, lay them on me.

But just being confident as you get up to have these discussions helps everybody else accept it, because most people are wired to trust their boss. And if a boss is smart, they create an environment that enhances that trust. And I’ve always done that by being well-informed as to the state of the business, sharing that with everybody, and being credible about it.

So at the beginning of last year, I was looking at the trends, and I said, “Hey, everybody, we’re about to have a great year. We need to hire some people.” We did. It worked out great. So then when you get back up and you say, “Hey everybody, things have gone to hell,” and we need to go the opposite direction, you have some credibility. And so how you relate to your workers to enhance credibility is something that you can’t suddenly start doing at the moment of crisis. You have to do it all the time so that you have credibility. And that’s part of what makes me able to have a certain measure of peace with my decisions.

Loren Feldman:

Paul, do you think maybe you risk some of that credibility if you start taking into account the personal situations of your employees? I mean, it seems like a really tricky calculation. You’re deciding someone has a particular circumstance that you’re concerned about, whether it’s buying a house or a sick relative or whatever it is, versus performance in the office. And if it’s perceived that you’re favoring one over the other, and the rest of the employees recognize that, is that something you worry about?

Paul Downs:

No, although when you put it the way you just put it, it’s probably something to worry about. And the other times I’ve had to do layoffs, it was like a wipeout. That was in 2008 where I had to lay off half the company one day. And performance in the office obviously is going to have something to do with it, but I don’t have any weak performers right now. So, I don’t know the answer to whether it’s more palatable when you realize the boss is taking into account those secondary things, or whether it’s just about: Are you the best on the shop floor, best here, best there?

We don’t really run an environment where people are competing with each other to be the best of whatever, and in a lot of cases, it’s not even possible to measure that contribution. But I’m going to consider that. For instance, if my best performer was a billionaire or something, and was just working for chuckles, it would be stupid to not take both of those things into account when thinking about it. If you lose your best person, who’s your second best person? Who could step in? Could we perform the functions? But the way I have the company staffed right now, everybody who’s here is capable of doing their job. So, then it comes down to secondary things.

Loren Feldman:

This is, I think, a challenge that smaller businesses have that big companies don’t. I’ve worked at some big companies that went through layoffs where the bosses had no idea about the personal situations of their employees. You know, they just did what they felt was right for the business. But when you work in a smaller group and you get to know people, how could you not take into account some of the things you learn?

Paul Downs:

Well, I think that that’s the plus and minus of running a small business. I enjoy knowing my employees. I enjoy every day I’m with them. They’re good people, and I like to have an environment where, when I walk in, everybody’s sort of glad to see each other. Then we’re getting work done.

And the opposite, that sort of soulless corporation—you know, we just treat people as numbers—that’s not how I want to live my life. So, I could run my business that way. I just choose not to, because I think that the person-to-person connections you get, even if they’re somewhat—I don’t want to say tainted, but—tainted by the power imbalance of somebody hires and somebody works for somebody else, and I have all the power in my hands to hire or fire or do whatever I feel like, that should not, in my mind, prevent me from having a decent human-to-human relationship with my employees. And I know that other people feel differently, but that’s how I want to have my life run.

Loren Feldman:

You told us that you’re basically doing all the same stuff this year that you did last year, when it all worked really well. Are you considering trying anything different now? Are you looking for other ways to drum up business?

Paul Downs:

No. I’ve always felt that if you suddenly try to shift your business into a different model, you’re quite likely to fail. Because anything that we could do differently than what we do, somebody’s already doing it, and they’re doing a better job, and they’ve got the marketing. And so me trying to do that as a short-term solution just seems quite likely to fail. When COVID came along, we sort of had a demonstration of that. Everybody was like, “Oh, we need sneeze guards. We need this or that.”

Loren Feldman:

The pandemic pivot.

Paul Downs:

The pandemic pivot or home office or any number of things. And I was like: We’re just going to get our brains beat out trying to compete with people who are set up to do that, because we’re not. And we don’t have the cost structure to deliver something different to the marketplace at a price that would beat what’s on Amazon.

And so I feel that we are in a very niche business that doesn’t have a deep set of market competitors who can do what we can do. And my suspicion has always been: Just ride it out, because every time these waves of difficulty come by, you lose even more competitors. And the piece of equipment we make—a big conference table—is not going away. People are going to need them. They’re going to need them 10 years from now. And so that if we survive this difficulty, and we’re the last guy standing, two years from now, we’ll be in even better shape. That’s been my approach for decades now, and I haven’t seen anything that made me think that that was wrong.

Loren Feldman:

What about not changing your business model, not changing your main function, but changing the way you try to attract business—different marketing initiatives, going after some different markets, but with the same product?

Paul Downs:

Well, we’ve been kind of trying to do that for years now, and the root of it is, Google is by far the most efficient way to connect someone like us with someone who wants to buy that there has ever been. And every other marketing channel that we participate in is mostly driven at the beginning by a Google search. Somebody finds us, and then we may turn them into a more reliable client, but it’s just driven by Google searches. And I don’t think that we’re gonna suddenly become the kings of TikTok or Instagram or anything, although I’m trying to post on Instagram a little more often and doing some LinkedIn stuff.

But I just think that we’ve got this thing that has been quite successful, and I have doubts about whether you could ramp up anything quickly that would be anywhere near as good, so I don’t really want to spend a ton of time doing something that keeps me from just keeping my eye on the ball of the operations we have here now. And that may sound like a very stupid thing to do. Everybody’s like, “Well, you could just be doing this, you could be doing that.” I’ve thought about all that, and I just don’t believe that we can make a quick pivot into other markets and other products.

Loren Feldman:

Are you spending more money on Google AdWords?

Paul Downs:

No.

Loren Feldman:

If that’s your best channel, why not?

Paul Downs:

I don’t think it makes much difference anyway, honestly. The only reason we give Google money for AdWords is just to give them some money. [Laughter]

Loren Feldman:

You’re looking out for Google.

Paul Downs:

I am looking out for Google, because Google’s been delivering for me for 23 years now. So, I think that they want money. We give them money. But the stats we keep on where calls come from suggest that the money is a waste. If you just considered: Okay, I spent this, and I got these number of calls, that seems like a waste of money. But if the larger project is to keep throwing things into the volcano to make sure the Volcano God is happy with you, then I’m happy to spend that money.

But I don’t feel like increasing it, because we don’t see much correlation between the number of clicks we get on any given day and who calls us. It’s almost entirely driven by organic traffic. So my theory is that Google, for all the things they say about there being no connection between organic results and paid results, I just don’t believe that. And I’d rather give them some money and make sure that I’m checking that box. It’s not a huge amount of money. It’s about 3,000 bucks a month at the moment, but it’s something. I feel like that’s worth throwing into the volcano to keep the Volcano God happy.

Lena McGuire:

They just keep changing the rules, too. With Google’s AI, the organic searches are coming below the AI information at the top. So people are reading what the summary is, and then they may not even go to the actual links to take you to an actual website.

Paul Downs:

All right, so anybody got Google pulled up?

Loren Feldman:

No.

Lena McGuire:

No, I can.

Paul Downs:

Okay, do this and then type in, “Who is the best custom boardroom table maker in America?” And I would be curious to see what the answer is. Like, if I do it from my IP address, I’m not sure what we’ll see. You’ve gotta use the word “custom.” And I could be thoroughly embarrassed here in the next 10 seconds.

Lena McGuire:

We have sponsored, sponsored, sponsored. Okay, so we have Chagrin Valley Custom Furniture comes up as the first sponsored. Sunshine Furniture is the second sponsored. Paul Downs Cabinetmakers is the third sponsored, and the first organic is Paul Downs Cabinetmakers.

Paul Downs:

Good. And I feel fine about AI. I mean, clearly, if it’s Chagrin Valley, they’re biasing the results for a local search to you. I’m presuming Chagrin Valley is somewhere near you.

Lena McGuire:

Yeah, so this doesn’t have one of those AI things at the top. This just comes up as the ads, so let me just put in custom boardroom table.

Loren Feldman:

Yeah, I didn’t get the AI either, and I got different results, but equally good for you.

Paul Downs:

Well, that’s good. I mean, that’s what I believe in, right? You know, that’s what I’m staking my business on—that process that you just did is still gonna deliver for me.

Lena McGuire:

You are not coming up first under “custom boardroom table.”

Paul Downs:

Who is?

Lena McGuire:

Casey Custom Hardwoods, and then customconferencetables.com.

Paul Downs:

Oh, that is me.

Lena McGuire:

That’s you? Okay. And then Greg Pilotti Furnituremakers.

Paul Downs:

Oh, Greg used to work for me.

Lena McGuire:

Stoneline Designs. Yeah, that’s the second organic one, yeah.

Paul Downs:

All right, so as long as customconferencetables.com is up there somewhere.

Lena McGuire:

Yeah, that’s the second organic one.

Paul Downs:

So, I think that I’m going with Google. And my feeling is the problem is not anything I’m doing, anything Google’s doing. I think it’s people are starting to feel very unsettled about what’s going to happen in this economy. That’s my theory.

Loren Feldman:

All right. Well, I just put the same question into ChatGPT, and it responded, “Selecting the best custom boardroom conference tablemaker in America depends on your specific needs, design purposes, and budget. Here are some reputable companies known for their exceptional craftsmanship and custom designs.” Number one: Paul Downs Cabinetmakers.

Paul Downs:

Great. So we worked very, very hard to make sure that we’re always putting in fresh content, and that we have good SEO. And one thing that’s been sort of in the back of my mind is: How were the LLMs trained about this, so that when people start using them more as just a basic search engine, are we going to score well? Sounds like, yeah. I mean, if there was some way for me to pay ChatGPT money for advertising, I would do it in a heartbeat, but I’m not aware that they have anything like that yet.

Loren Feldman:

I’ve been told that the things that improve your SEO with Google are likely to improve your results on ChatGPT and the other LLMs as well.

Paul Downs:

Yeah, it wouldn’t surprise me.

Loren Feldman:

So it makes sense, given that you have the history that you do, that you would show up well on the AI LLMs.

Paul Downs:

Well, I’m glad to hear it worked. And for those of you listening out there: No, this was not a setup. It was not fake. [Laughter] I sprung it on him, risking that it would turn out there would be somebody there, and I wouldn’t be in the results at all.

Loren Feldman:

Paul, I think our listeners would be very happy if they were to hear that this got you some business.

Paul Downs:

We’ll see. [Laughter]

Loren Feldman:

I wouldn’t worry. Let’s go on to something else. Unfortunately, it’s not too much cheerier, but I want to get your reactions—especially yours, Lena—to a recent post on the small business subreddit. It comes from a somewhat distraught business owner who wrote, “So, yeah, I quit my high paying job to build my own startup. No co-founder, no big savings, just an idea I couldn’t get out of my head. I had a comfortable life, but every day, I felt like I was wasting time working on someone else’s dream. Now I wake up stressed, I go to bed stressed, and my brain never stops. Some days I feel like a genius. Other days I wonder if I just made the dumbest decision in my life. It’s a constant cycle of this is going to be huge, and what if I fail and have to crawl back to a job? Money’s running out faster than I thought, of course, and I’m realizing that building something people actually want is way harder than just building something cool. But at the same time, there’s this weird excitement in the chaos. Even if I fail, at least I took the shot, right? If you’ve done this before, how do you stay sane? If you haven’t, would you ever take the risk?” Lena, how do you respond to that? Because you’re kind of doing something similar.

Lena McGuire:

Yeah, welcome to owning a business. That’s exactly how you’re supposed to feel, and it doesn’t really go away. You just learn how to deal with it. So the ups and downs of owning a business and learning how to run a business, how to be a business owner, that’s all par for the course. I think you’re in good company. I think the reader has what it takes. It sounds like they’re doing what they need to do, and they’re having the same kinds of fears that every entrepreneur does. The key is to figure out what is your bottom line, as far as your finances. You don’t want to lose your house, you don’t want to lose your spouse, so you have to know, if it’s really not working, when do you go back to that job? Or do you take a side hustle?

Because when you start a business, I know for myself, personally, it was about two and a half to three years before I could take a paycheck, because every time you make a profit, you roll it right back into the business, basically, because you have to. So how you set up the business, I think is key. I went through a Score fast-track training that was invaluable. Most of the SBDC centers will have a course. It’s around $100 or $125, a five-day thing. And it teaches you the importance of having a BAIL team, which would be your banker, your accountant, your insurance agent, and your lawyer. That’s going to help you set up a stable foundation, which is where I made my mistake. I did the course twice, and I still only have a banker and insurance agent.

I’m just now going into my third year here, working with an accountant and a bookkeeper. I have an attorney, but reviewing contracts and actually having contracts that are consistent, that are boilerplate, that I could just use, that’s something that’s a work-in-progress. So, yeah, there’s a lot of things that you have to do. And getting a support group of people who are in your shoes, that I think is the most helpful thing you can do. Get that foundation set, and get in contact with other people. This podcast is a great place. You listen to other people, you realize they have the same issues that you do, and they have issues that you’ll face in the future, so you’ll be better prepared for them.

Loren Feldman:

Lena, in your first episode here, I think you told us that you and your husband sat down and decided how much money you wanted to put into the business. Was that also a decision of how much money you were willing to lose?

Lena McGuire:

Absolutely. In my mind, I view the money differently than my husband does. We both agree it’s a capital investment into the business, and the business is going to get us a better return than any other investment we could do. We both believe in the business. But I look at it as a loan from my family, that if I lose this money somehow, it’s going to hurt my family. But in reality, we have enough that we’re not allowing that much money to come out that it would hurt us. And if we lost all of it, it wouldn’t hurt us.

So these are hard conversations to have. You have to wrap your head around reality. What does the business need? And we’re not talking: I need a couple hundred dollars, I need a couple thousand dollars. I mean, I’m opening a showroom for a kitchen dealership. A hundred thousand dollars is a drop in the bucket, but that’s my initial investment. So you’ve got to do your cash flow statement for your personal, and then do the cash flow statement for the business, and see what those lowest month numbers are. And you’ve got to be able to cover the bills every single month.

Loren Feldman:

Are you committed to the idea that if you did, in fact, run through that money, you would shut down the business?

Lena McGuire:

I would have to make some hard choices. I don’t know that I would shut it down, but I would probably get a side gig going, work part-time, like I did in the beginning, to get my first studio space. I did do a part-time job about 20 hours a week for two and a half years until I could fund myself, and then I quit the part-time job. But if I had to go back, I would. You do what you have to do. Having a business is like having a baby. You have to take care of it and nurture it, and ptu the time and effort into it.

Loren Feldman:

You can’t shut down a baby, though.

Lena McGuire:

Yeah, true. But if you have adult children who are living with you, you can kick them out. [Laughter]

Loren Feldman:

Paul, you started your business a long time ago, but did you go through that kind of thought process?

Paul Downs:

Yeah, although I was 22, so the consequences of failure were pretty, pretty low. I think that, thinking back about, “How do you stop worrying?” part of it is: Are you making small gains along the way? Like this person started some business. We have no idea what the product is or what it should be doing, but when you can start to get people paying you for your thing—who aren’t related to you—then that starts to be a confidence booster.

But there has to be a trajectory to it. You’re never going to be all that good at what you do the day you open. You’re going to have to practice. And so hopefully what you’re seeing is some clients signing up that give you the opportunity to do the thing you wanted to do and get better at it. And as you go along for longer and longer periods of time, that confidence becomes more internalized.

Like, okay, I’m going through a pretty bad year this year, but I could point to other years and other projects, and I can say, “Listen, we actually know how to do what we’re doing. We’re not failing because we’re idiots. We’re failing for a different reason.” But at the very beginning, you just don’t know whether you’re going to fail or not. So I don’t think there’s any way to avoid going through that process of self doubt—unless you’re completely deluded. But you’re going to doubt, and what you need to do is be looking for reasons to not doubt.

The reasons to doubt are always going to be pounding on your door. People are going to tell you it’s never going to work, and you can see your own money disappearing, and whatever. You don’t need to drum up any reasons to worry about things. What you need to do is look for the things that can give you some confidence that you’re on the right path. And if none of those are appearing, then, yeah, you’re on your way to failing.

So it’s not an easy place to be. I don’t think that most people are wired to really succeed as entrepreneurs because of this thing, which is: It’s really, really hard to keep your head in the game when times are tough. So, good luck to that person.

Lena McGuire:

Yeah, there is an exercise you can do that I learned from coaching. It’s a reflection exercise. So if you sit down once a month or once a quarter and you write down all of your accomplishments, like maybe I am no longer getting jobs from my family. I had three new clients, and these people are not people I knew. Or I got phone calls, or I completed something quicker than I thought, or I made extra profit on something.

So you just write down your accomplishments, because it is so easy to focus on, “I didn’t do this. I didn’t accomplish that.” But if you look back and see that you did—like Paul was saying—you have these small steps forward, you get that confidence. And it makes it much easier to keep moving forward, because it gives you the strength to see that, “Yes, I can do this. I have done this. Look, I have evidence in the past.”

Loren Feldman:

Lena, I think you also told us previously that last year was not as good for you as you’d hoped. Your top line revenues fell short of your goal, but you were able to maintain your margins and you still managed to make money. Did that happen by design, or was there some serendipity to that?

Lena McGuire:

Losing the business was not by design, but maintaining the margins was. So, the reason I lost business, or revenue not coming in, was because I had not done any marketing. I was flying high on a high-growth period where I had more work than I could do, and I just didn’t see the need to market. But what I was working on while I was doing all this was maintaining the margins.

So every time I had a new project coming in, I was looking at those line items and doing a post mortem on the projects I’d completed to make sure that the numbers were aligning, so the actuals versus the projected were in line. And I was very good at keeping that margin that I need to run my business. So even though I had about a 35-percent decrease in revenue, my earnings were exactly the same as the year before. And that gave me the confidence to say, “Okay, I did something right. I just need to do the thing that I didn’t do right, which was the marketing.” So now I’m working on the marketing, but I’m still maintaining those margins and still watching them like a hawk to make sure that every business, every project that I do, is going to come in and make money for me, and not be a loser.

Loren Feldman:

By managing that, you’re increasing your runway and giving you more time to keep going and get your footing.

Lena McGuire:

Yeah, and I’m also watching that cash flow so that when the dip months come in, which for me are between November and March—I live in the Central New York area, where it’s snowing, and people aren’t anxious to remodel their kitchens and cook outside like they are in the summer. So we typically have a little bit of a slump in the winter season.

I don’t have as much revenue coming in, but the bills are still the same. I still want to take a paycheck. So having enough in the reserves to cover all the bills and your paycheck without the revenue coming in is key. And that’s where, when they say cash is king, to me, that’s pretty much what it means. Can you cover your lowest points without begging?

Loren Feldman:

All right, well, last thing, Paul, I’m curious: Aside from generously spending your time with us here, what do you anticipate you personally doing over the next week as you deal with this?

Paul Downs:

Well, that’s one of the things that’s toughest for me to deal with, which is that I’ve got people doing most of the operational roles that there are in the company. And so it’s not like I could suddenly shoulder aside one of my sales people and do a better job. They’re good at it, and so I’m just kind of waiting it out. See what happens: how many people call us, what happens to them. We’re being a little less picky about jobs we work on. We’ll give anybody a price for anything at this point. And a year ago, it was not that. We were being more choosy about only concentrating on projects that looked like they had a high chance of success.

But aside from just watching and waiting, there’s not any huge change in the things that I can do every day. I just have to have some faith that we’re going to get through this one way or another. And that’s the flip side of what people are talking about when you grow the business and you’re trying to get yourself out of the operational roles and just be more the leader and the boss. That’s great, until a day like today, when you’re just like, “Okay, I can’t do anything differently, other than watch the company try to perform.” And it is mentally tough. You know, I’ve got this feeling in my stomach every night when I go home that just feels like a ball of pain in there, and I just have to tough it out. And so, no easy answer to that one.

Loren Feldman:

I can imagine that being really frustrating. I mean, obviously, as you said, it’s a great thing to be able to pull yourself out of the day-to-day and have your business be able to operate without you. But sitting there, not being able to dive in and do something at a time like this, I can imagine why you have that ball of pain.

Paul Downs:

I’m also very cognizant that I don’t want to hover around my people and just let my nervousness fall all over them. I think that’s a bad thing for leaders to do, that people need to feel that the one in charge has some guts and some courage and can be the calmest one in the room. It makes it easier for everybody else to perform. And so that’s been my approach so far.

I’ve been through a lot of crises in the business. I just basically feel like people want to feel like you’re not panicking. And so if the boss looks like they’re panicking, everybody will panic. If the boss looks like they’re dealing with it, then everybody can keep their eye on what they need to do.

Loren Feldman:

Well, listen, it’s easy to talk about your business when things are going great, and happily, sometimes we get to do that. But I really appreciate both of you talking about what it’s like—especially you, Paul, right now, when you’re going through it. My thanks to Paul Downs and Lena McGuire. I really appreciate both of you sharing.

Paul Downs:

Glad to be here.

Lena McGuire:

Happy to help.