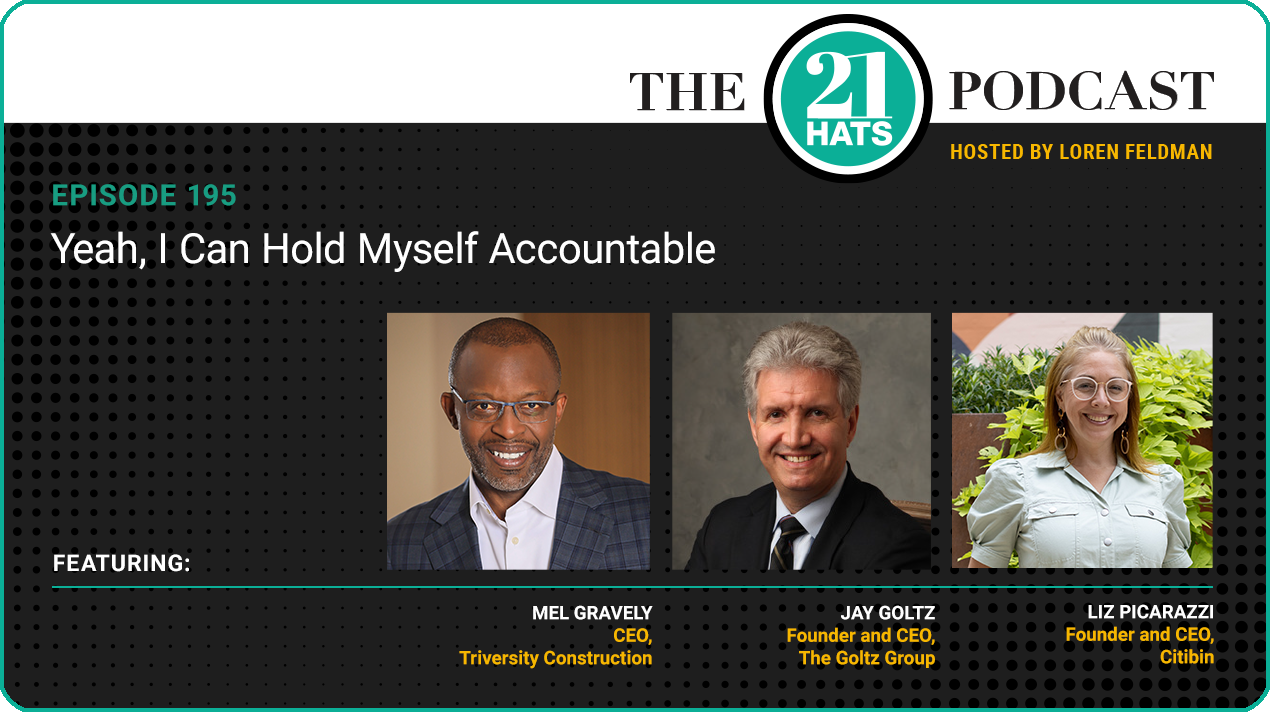

Yeah, I Can Hold Myself Accountable

Introduction:

This week, Mel Gravely tells Jay Goltz and Liz Picarazzi about his recently executed succession plan, including what’s worked and what could have gone better. The main thing that could have gone better, Mel says, is his purchase of another small business where he says he misdiagnosed the challenges the business is confronting: “I thought they just had a bad model and they weren’t managing it well. It was worse.” All of which leads to a discussion of the role that a board of advisors can play in helping an owner build a business. While Mel has said he wouldn’t run a lemonade stand without a board, Liz and Jay—like most business owners—have taken a different approach. The notion of having a board of advisors, Jay tells us, is something he struggles to get his head around. “I’ve been doing this for 45 years,” he says, “and I’ve never had anybody to answer to.” Plus: with the talk of tariffs getting louder, Liz updates us on her search for an alternative to manufacturing her trash enclosures in China. “We really have to have a Plan B,” she says. “We’d be stupid not to have a Plan B.”

— Loren Feldman

Guests:

Mel Gravely is CEO of Triversity Construction.

Jay Goltz is CEO of The Goltz Group.

Liz Picarazzi is CEO of Citibin.

Producer:

Jess Thoubboron is founder of Blank Word.

Full Episode Transcript:

Loren Feldman:

Welcome Jay, Mel, and Liz. It’s great to have you here. I want to start today by talking about succession. I recently highlighted a story from The New York Times in the Morning Report that painted a somewhat bleak picture of retirement for business owners. It focused on a particular owner, who apparently had sold his business and was now puttering around the house while his wife continued to work remotely as an executive. She had a team of employees. The story is told from the point of view of the woman who clearly isn’t thrilled that her husband is home all the time, offering lots of unsolicited advice about how she runs her Zoom meetings and manages her team. She starts to wonder what he must have been like as the boss of his own business.

It’s clear they lived lives on separate tracks. He ran his business. She worked her high-level job, while also raising the kids. There’s a poignant exchange where he says to her something like, “Wow, our grandkids are so bright and interesting.” And she responds, “You know, your own children were very bright and interesting, too.” [Laughter]

I don’t want to suggest that any of you are headed in that direction. But I think you might be able to relate to some of that or share some of those concerns. Mel, you recently went through a transition. It’s not the same. For one thing, you haven’t sold your business, you just stopped running it on a day-to-day basis. But having gone through this, I’m curious: How’s it going?

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, I would say, first of all, I pray my daughter, my sons, and my wife would not report that I was that as a parent when I was running the company, and hopefully I’m not that now. So I would have to say it’s going well, Loren. You know, it is a transition, but mainly an emotional one. You know, when I visit the office, no one asks me a question. No one seeks my opinion. It’s not that they don’t care what I think—well, maybe it is that they don’t care what I think. Well, maybe it is.

So that part’s different, from an emotional standpoint. I am working from my home now, but I’ve got so many things I’m interested in doing. And I still do help out with access for the company, and the CEO and I have a formal check-in cadence, and I still chair the board. So I’m still active there. But I’m on a number of other privately-held company boards and I’m active in the community. I’m writing again. So you know, it’s working out pretty well.

Loren Feldman:

You put a lot of thought into this. I know you planned it out. You talked to a lot of other people who’d been through it. Looking back on the way you managed the transition, are there things you got right? Are there things you got wrong? What would you highlight?

Mel Gravely:

Well, first, I highlight the fact that it’s May, so it’s been five months, right? So you know, July or August, it could all fall apart. I could be an emotional trainwreck. I could not resist my urges to go back in and take over. So it still could go bad. But with that said, I think the planning of not just the transition, but what I do with my time, was pretty important, so that I have less room to meddle, less room to worry, less room to get in the way.

I think the other part is being clear why you’re doing it, because it makes it easy for me not to look back. Because I’m very, very clear about why we did it, why we’re doing it now. We probably could have waited one more year, but I think we were in the ballpark of getting the right time frame. So what I would say: I could have spent more time on, been more thoughtful about, is when I purchased the other little company I bought last year, I probably should have given that a little bit more thought. But other than that, I think I’m pretty pleased so far.

Jay Goltz:

So give us some context. Who took over? Did you bring in him/her from the outside? What’s the story with who you left in charge?

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, the current president/CEO, and my business partner—he now owns 10 percent of the business—is a guy that’s been with me for about 11 and a half years, almost 12. It’ll be 12 in November. So we acted as partners for years, to be honest with you, Jay. And he’s a great guy. He’s a construction guy, and I’m not, so he brings a certain sensitivity to the business that I just don’t have. He’s gonna make the company more profitable, because he knows how, and I’ll be out of his way and stop spending money. But yes, he was with us for a long time.

Liz Picarazzi:

When did he get the 10 percent?

Mel Gravely:

He got the 10 percent—don’t hold me to the exact date—it wasn’t at transition. He got the 10 percent in 2020 or so… maybe ‘21. I really can’t remember, but he got it before he became CEO. He was actually offered some ownership prior to that that he declined at the time for personal reasons, but was glad to get it when he got it.

Jay Goltz:

So what’s the long-term? Because, you know, I’m eight years older than you are, but at some point, we’re gonna die. [Laughter] Do you have a long-term plan? Because my wife, her father died when he was a year younger than me. And she has brought up to me, like, “What if?” And I don’t have a great answer at this moment? I’m certainly working on it. But do you have a great answer?

Mel Gravely:

I don’t know if it’s great or not. Prior to me leaving as CEO, we had a two-pronged plan. One was an emergency plan: What would we do immediately? And then the other was: What will we do long-term? Keep in mind that this business, although privately owned, is stewarded by a fiduciary board of directors. So there are seven people who are in a position to protect the company as it moves forward. So if something were to happen to me, at least there are stewards of the business.

But now that I’ve transitioned to chairman of the board and majority owner, the plan is a little bit different. So the long-term plan? I don’t know. We’ve got a long-term framework. It starts with the board. My oldest son is on the board. His brother will join. His younger brother will join in June as an advisor to the board. So they’ll learn how to be fiduciary agents of a privately-held company. Maybe they’ll get the itch and want to join the company, but that’s not an expectation. So right now, if you said, “Mel, what’s your plan?” It is to own the business as a family forever and teach the familial successors in: How you motivate a management team and be good stewards of a family asset?

Jay Goltz:

So of the seven people, do any of them work in the company?

Mel Gravely:

Yes, they do. The board seats are held in proportion to ownership. So I control four seats. There’s another entity that owns 20 percent of the company. They have two seats. And my partner and now CEO holds his own seat. So he works for the business. I guess I kind of work for the business. Everyone else is outside of our company. So two of the five are employees.

Jay Goltz:

Your situation is 100 percent different than mine. I have no board. I understand it sounds like, for you, that works fine. And it makes sense.

Loren Feldman:

Let me ask, Mel, did you create that board? I know you bought the business. Did you inherit the board? Or did you create it?

Mel Gravely:

No, I created a board the first few months that I bought the company. There were only three people at the time, because there were three owners, and so everybody had a seat. And then as we transitioned ownership, and I wanted to expand the role of the board, we grew it. And so the board members are either selected or negotiated with the owners about who sits in those seats.

Loren Feldman:

What motivated you to start the board?

Mel Gravely:

Two reasons: One, I think I needed to be held accountable, because we all have those things we keep doing that are not that smart, but we just keep doing them. And so I needed some accountability there. And I don’t like it—actually, I dislike it. But it’s been very, very important. The second reason is, I don’t know how you go from generation-to-generation without the continuity that a board can provide for you. And so from that standpoint, if you really want a multi-generational business—

Loren Feldman:

And you were thinking about that way back when you first bought it?

Mel Gravely:

Oh, absolutely. Multigenerational was the reason I wanted to grow a company of scale. I think you know a little bit about what I’m out to prove, but yeah, at the very core of that is this has got to be multi-generational, and that, above all else, is important to me.

Loren Feldman:

You mentioned the business you bought last year and that you should maybe have put some more time into it. What was the motivation there? Did you buy this business as something that you expect to really focus on, now that you’ve kicked yourself upstairs from your main business?

Mel Gravely:

Actually, I bought it because I always loved this business. I was hoping that I could convince Triversity—the company that I was exiting to—over time, to see the value in it and add it to its portfolio of companies that it owns. And so that was the motivation, right? They were not buying in. And so I decided to buy it myself, and convince them over time that it was a good idea.

Loren Feldman:

It’s a construction-related business?

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, it’s facilities management. So it’s the grunt work. Plus, you know, little patches of drywall all the way down to mowing grass and moving snow and cleaning out gutters and cleaning windows. It’s the ultimate execution business. But good companies during even bad times, they’re going to maintain their facilities well. And so to me, it was an offset to the economic kind of trends that construction can lead itself into. But it is a tough business. And the company I bought, I misdiagnosed their challenges. And now I’m in a situation where, now I understand the challenges, and they’re tough ones.

Jay Goltz:

How many employees are there all together?

Mel Gravely:

In Triversity or the new company?

Jay Goltz:

No, everything under your purview.

Mel Gravely:

150 people, maybe, total.

Loren Feldman:

And the new company, are you managing it on a day-to-day basis?

Mel Gravely:

No, there’s a president in place. If I had five years, he’d be great. But I don’t have five years. And he’s got to giddy-up a little faster. He’s bright. He knows this business super well. So I would have to say he’s managing the day-to-day. But I’m very involved, Loren. I’m very involved. And I’m not used to being very involved. So it’s a challenge.

Loren Feldman:

Can you give us a sense of what the main challenges are? Why is it a tough business?

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, the fundamentals are, this company, when I bought it, had one customer. So that, to me, is not a problem, because they had an amazing customer—a very large customer for this kind of business. And we were performing very well for them. So I was confident that our ability to perform was going to be a base for us to grow this business. What I misdiagnosed, I thought they had a management problem. They had a structural contractual problem with the customer that is just… We were actually paying the customer to show up every day. And the team just didn’t know it. I had never seen negative gross margin before, literally never seen negative gross margin. And when I saw it, I just knew it was a mistake.

So that’s the biggest challenge. The good news is that it’s a great customer. We’re working through new contract terms, new bill rates, that will put it back to profitability. But you know, when you dig a hole as deep as we dug it, it just makes it a challenge. The second thing about this business, it is very cash intensive. When you do business with big customers, 90 days are good terms. And so you’re paying weekly, because that’s the kind of employees you have, and you’re getting paid in 120 days. So the cash that it can consume is significant. So you add the cash that it consumes to lack of profitability, and it becomes very difficult.

Jay Goltz:

Wait, wait. See, this is what’s interesting about this podcast. We’re very different. Everything you’ve been saying up till now, it’s like, “Yeah, that ain’t me.” I mean, we’re on opposite ends of the spectrum. You’ve got a bunch of partners; I have no partners. You’ve got one customer; I’ve got 40,000 customers. You finally hit on something. Okay, I got my arms on this one. What’s with 120 days? Why do you have to wait 120? And what if you say to them, “You need to start paying quicker”? Why do you have to live with 120-day payment terms?

Mel Gravely:

That’s a great question. You don’t have to, but you do have to if you do business with them.

Jay Goltz:

So you think, this particular customer, if you say, “We can no longer finance this at 120,” Do you think they’ll find someone else that will do it for 120 days?

Mel Gravely:

I guarantee it.

Jay Goltz:

Wow.

Mel Gravely:

Now here’s the nice thing. If you’re smart, though, and you’re profitable, you just build a carry into your business model. But you’ve got to build the carry into your business model. And if you don’t, then you’re going to be really hurting. Triversity, the construction company, does business with the same customer. We’ve never had a problem with the 120 days. We have some problems with our subs that can’t wait that long. But we’ve never had a problem with 120 days, because we’ve built it into our business model.

Loren Feldman:

Are you looking for other customers?

Mel Gravely:

No. Well, here’s why. I’ve got to make sure that I can cash-flow a new customer. The worst thing I could do today is get a new customer. The customer would have to pay me upfront, and at scale, those are hard to come by. When we get this model straight, though, I’m confident. The customer and I are very clear about this. We can get back to 120 days. We can continue to deliver at the A-plus level that we’ve been delivering. And then we can start to add customers.

Jay Goltz:

You say you have negative gross margins. I assume you’ve got to charge more, right?

Mel Gravely:

Oh, absolutely.

Jay Goltz:

Okay, so my question is: Are they going to find someone else if you raise your prices where they need to be? Are they going to find someone else who’s going to go ahead and do it cheaper because they don’t know the difference? Is that a question mark?

Mel Gravely:

It’s not a question for me at all, because we’ve been very clear: Please do find someone else that could do it at this price, and they can have it. You know, when you get super clear about it, the customer gets super clear, too. And they’ve been great. Because what I said is, “I’m going to show you everything, all the costs. And you tell me that you’re paying for what you’re getting.” Now, they never admitted, “We’re not paying for something that we’re getting.” What they did say is, “We’re willing to talk to you about the pay, to raise the rates.” So they’ve been great about it, to be honest with you. But it’s not their job to make sure I’m profitable. They want me to be profitable. It’s not their job.

Jay Goltz:

So, the interesting business question to me is, the people that you bought this from—I’m gonna guess they didn’t have the proper accounting people in place to recognize that they were doing it at a negative gross profit. Is that true?

Mel Gravely:

That is correct.

Jay Goltz:

It comes down to accounting.

Mel Gravely:

It does. And an idiot that would buy it without believing the pro forma because this company did not have the model change. I’m gonna try to keep it short. This company did not have financials when I bought it. It didn’t even have employees when I bought it. The two owners prior to me were loaning employees to this business and charging the business 10 percent margin for the cost of carrying those people. So they had no purview into what it was actually costing the company to do this because they didn’t care. Because they were both getting 10 percent on all their employees. Where they did care was, they couldn’t seem to cash flow. That’s why I misdiagnosed. I thought they just had a bad model and they weren’t managing it well. It was worse. They had a bad model. They weren’t managing it well. And they had no idea what it cost to deliver the service.

Loren Feldman:

Are your friends at Triversity who decided to pass on this purchase aware of your challenges with it?

Mel Gravely:

They’re not only aware, they have shown up like the troops that they are. The people who have figured this all out are my very talented CFO and controller at Triversity. The human resources at Triversity are now the human resources in this little company. They are showing up to save my bacon. The CEO is kind of like, “Dude, could you get this over with? Because we’ve got work to do.”

Jay Goltz:

You know what’s funny about this whole story is, like I said, every single thing I ticked off that you were going through, “Yeah, that’s not me. That’s not me. That’s not me.” And now? “Boy, that’s me.” I’m having the exact same issues with accounting, with figuring out: Wait, I’ve got four businesses. We’ve been allocating expenses to them. And oops, that’s wrong. And I’m in the same spot you are with the accounting thing, which gets to: I’ve never met a company that’s super successful because they’ve got great accounting. Though I’ve met lots of them that failed because of bad accounting. So, accounting is critical. That’s the moral of the story for today. Accounting is critical.

Mel Gravely:

Well, I think accounting and finance—and they’re different in my mind, at least. You know, accounting is making sure I’m allocating costs correctly. The finance is around strategy and projection, and it drives what we buy and all of that.

Jay Goltz:

Yeah, absolutely.

Loren Feldman:

Liz you’re a ways away from needing to think about succession issues. But does this conversation get you thinking about it at all?

Liz Picarazzi:

Yes, it does, in that, when I retire, I think I probably will retire, but I’ll have some sort of limited business interests. I’ve often thought, if I sold my business, then I would have some years of angel investing, partly because it just would be really interesting to me to be a part of that. But hearing Mel’s tale, I would be very cautious to take on a challenge like that. Because it kind of sounds like the opposite of retirement—sorry, Mel—to be honest. [Laughter]

With succession, I haven’t done a lot of thinking about it. My daughter is 18. She’s going to college in the fall. She knows that if she wants to be involved in the business, she can. Like many 18 year olds, I don’t think she’s going to be interested in that for a while. So in terms of familial succession, that’s something I think about. But also, I’ve got incredible employees. And I have no idea how exactly I would structure it, but if I had a way without going the whole ESOP complicated route to enable my employees to run the business, to own part of the business, I would be interested. Whenever I hear here on the podcast, or I went out to Fort Worth for 21 Hats, and I hear about ESOPs, I just kind of close my ears at this point, because it all just seems so complicated.

But that’s kind of what I have in mind. If I did have an offer to sell the business, that seems like it would make a lot of sense, particularly if it would free Frank and me up to do a lot of things we love to do. I love to travel. I love gardening. I think that may sound crazy that I would really want to give up my business to pursue gardening and travel. But the truth of the matter is, I think I probably would. If I could have a lot of cash in the bank from selling my business, and I could just pursue hobbies, like home renovation and traveling, I would.

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, Jay mentioned that he doesn’t have a board. You don’t either, Liz?

Liz Picarazzi:

I do not.

Mel Gravely:

But Jay, you almost said it with a sense of pride.

Jay Goltz:

I’d have to think about whether it’s a sense of pride. I mean, I hear what you’re saying. That’s a lot to process. And I’d have to figure out who would be on the board. And certainly, listen, as you know, I spent a lot of time looking at ESOPs over the last couple of years and have come to understand that one of the things that I should be thinking about is having a board. And who would it be? And how involved would they be, given that no one has any equity in the business? Though, in your case, you had no choice. That goes with the whole thing. So I just have to think of the word.

Loren Feldman:

Wait, why do you say Mel had no choice?

Jay Goltz:

Well, he had people that own stakes in the business.

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, but I could drag them around like I own them, because I own 70 percent of the company. So, no, I didn’t have to do a board.

Jay Goltz:

But it was more natural because they have stakes in the business, so it makes more sense that they’d be on a board. In my case, I guess it’s on my to-do list—not guess—it is on my to-do list. Because I do need some people here who can help give some direction or whatever for the day that becomes necessary. I guess it’s not that I say it with pride. It’s so unfamiliar to me that I really have to get my head around it. I’ve been doing this for 45 years and never had anybody to answer to.

And also, when you said you need someone to hold you accountable, I laughed to myself, because whenever I would join a business group, they’d go, “Well, it’s good because you can be held accountable.” I always say to myself, “Yeah, I can hold myself accountable.” I don’t need to be in Vistage to have a group of guys holding me accountable.

So that’s just the world I’ve been in, though I can’t argue with the fact it’s good. Listen, I have one of my kids here. He’s holding me accountable every day. He’s bringing up stuff that I should have been paying more attention to, and he’s absolutely right. So I am getting some of the accountability thing. So it’s just unfamiliar territory to me, and I’m having to get my head around it, with the knowledge that I do need to do that. That’s just something I have to work on. But again, just totally unfamiliar. And you have to think about it. And so this is all very interesting.

Mel Gravely:

Liz, what are your thoughts on the board thing?

Liz Picarazzi:

I’ve often thought of creating something informal. I mean, I’m 100 percent owner of the business. So I don’t have board seats that I need to give to investors. But I’ve thought of it less as a board of directors, and more as a board of advisors. And a few years ago, I thought about trying to convene a group, like physically or even by Zoom, all together, maybe quarterly. And I gave up on the idea because I felt like that was sometimes too much to ask of people. And that what I’m really looking for is to get advice from people, that I should just seek out the subject matter experts in areas that I want to move into.

So let’s say I wanted to get into more municipal contracting, or I wanted to get into higher ed, or I wanted to work with more multifamily developers. These are all areas where I’ve made good inroads into those markets. But if I could have advisors that would say, “Hey, you might try this, this and this, you may call this person,” that would be incredibly useful for me. And if it were the right board of advisors, I think people get something out of that. People like to help people. And if they offer a strategy that ends up working for my business, that makes everybody feel good.

So I do have some interest, in that it’s been on my list for a long time. But I know recently, we were talking about really having a budget to take people out to lunch. And this may sound really simplistic, but I was thinking that budgets could be like, considerably less than having a board of advisors where I just take interesting people out to lunch that I think might be able to teach me something. That could be really useful.

I do get a lot out of EO, and it’s not really an accountability thing. There’s a piece of that. But a lot of it is being in a network for whatever question that comes up that you can ask the question in a huge group. In my case, EO New York has 200 members. And I’m most likely going to get an answer, and it’s going to be a good referral. So if we’re saying Board of Directors, no, that’s not something that’s in my near future. But board of advisors? I think I could be doing more on that. And doing it more in a dedicated way, where, say, I take one or two people out to lunch every month. And then I get to look forward to it, too, by having an interesting conversation in a nice restaurant.

Jay Goltz:

Or just having lunch, just being able to have lunch.

Liz Picarazzi:

Actually taking time to have lunch, yeah. But sometimes I’ve thought about it too. Like, I’ve spent really dumb money on Google AdWords over the years, which got me nowhere. A few years ago, I said, “I’m not going to spend a dime on Google AdWords or Facebook or any of those. And I’m going to take that entire budget and put it into having lunches and doing things with people that can actually make a difference in my business.” And so that’s sort of my approach to how I take in outside involvement and perspective.

Jay Goltz:

Let me put you on the spot then, and ask you—because we’ve had numerous meetings here, in Texas, on the phone, on the podcast. And I have given you, I’d just call it a hard time, on several issues. Which, off the top of my head, one: I have encouraged you to buy some warehouse, buy real estate. Two, I questioned whether you were paying yourself enough money, and your husband, so that your financials are truly accurate. Or are you subsidizing your business by not pulling enough out at what could be called a market rate? And three, about having inventory, which I think that you’re kind of on the same page. But on those first two? Am I wrong?

Liz Picarazzi:

So, Jay, you have made a difference. I’ll start with the second issue, getting paid. Yes, Frank and I were subsidizing the business for many years. And this year, we’re not. We basically doubled our salaries—bam, done!—and said, “If we can’t afford this, then we’re gonna have to really question this business.” So far, so good. We figured if we can’t afford to pay us the market rate that we are now getting paid, that we may do one of your favorite strategies, Jay, which is to raise prices again. But I don’t want to move ahead with that sort of price increase right now, because it’s likely going to need to happen if the tariffs are raised with China.

So that’s number two. On number one, investing in a warehouse, I love the idea of it. I already have a large SBA loan, and I don’t feel comfortable taking on more debt. I feel like our supply chain issue with having our own warehouse has partially been figured out, because we moved from a 3PL to our own space that we rent and that we’re not paying inflated rates on. Because it’s just like we rent it. It’s ours.

Jay Goltz:

The rent that you’re paying isn’t any more than you’d be paying if you owned the building? I mean, did you do an analysis to see if—

Liz Picarazzi:

I probably should do an analysis. But remember, I live in New York City, Jay. And there’s a lot of people that have the same idea about warehouses in and around New York City. And I’ve just found that, if you want to buy a warehouse, it’s still crazy expensive. It’s not something that I see myself taking debt on in order to get a position in. But ask me again in the future, I don’t mind discussing it.

Loren Feldman:

Jay, those are really good questions. I can’t help but point out, though, that it strikes me that they’re the kind of questions that a board would ask Liz. I think you’re kind of making the argument for having the board that you don’t have.

Jay Goltz:

No, I absolutely am. That’s why I was curious to see whether any of that sunk in, because if it didn’t, I’d say, “Well, these were pretty obvious things.” And she said it made a difference, okay. Because if not, there are some people—I don’t think Liz is like that. I know, I’m not like that. I absolutely listen to everybody’s input and think about: Okay, maybe they’ve got something.

There are some people who just don’t listen to any advice and just keep doing the same thing over and over and over. I’ve seen it when I was in Vistage. You go to meetings, a year later, you’d say, “Wait, wait, wait, we talked about this a year ago. I thought you were gonna—” And nothing changes. They just keep doing the same thing year after year, which is partially why I got out of Vistage. It just got frustrating. They acknowledged they were doing it wrong, but they just keep doing it for years.

Loren Feldman:

Mel, my sense is that the decisions that Jay and Liz have made about having a board are more common than the decision that you made. My sense is that a lot of people who choose to start their own business do so because they don’t want to have a boss, and they’re not looking to create one by starting a board. Is that your experience as well? Do you feel as though you’ve taken a slightly different path than most of the business owners you know?

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, I would have to say that the majority of business owners don’t have a board. And if what Jay took away from my comments is that it is all about accountability, then I’ve done a horrible job of talking about boards and board importance. In my mind, there’s no difference from a structured board of advisors and a structured board of directors, except the fiduciary responsibility. I bet we don’t vote more than four times a year on anything on that board. So it is almost always advisory.

Loren, one day I’d love to—and maybe you guys have already done this—just take a single-topic day on: What do they look like? And what value do they bring? Because every question that Jay asked Liz are things that boards can work through, but they work through them with a deep level of context, because they meet every quarter. They understand the business. They understand the business owner. They understand their personal situation. So when they give advice, it is contextualized over time, so that they would have known about debt and about Liz’s belief, and how much she wants and how much she doesn’t. It’s just such contextualized advice, that if you said there’s one thing that’s magic—and I think I’ve said this on this podcast before—having at least a board of advisors that meets quarterly is just transformational for the leadership. I just can’t express how much it changes and how much it adds to leadership.

Jay Goltz:

I fully accept that. Here’s the issue I’ve had: Where do you find these people to be on the board?

Mel Gravely:

You know, I’ve got to count. I’m probably on four boards of advisors, maybe three, of companies that are pretty small. And the way I got on those boards is, in some of these groups I’m in, you get to meet people. You have a meal with them. You have a drink with them. They like you, you like them. You talk more about business. You like the way they think. And you ask them, and they either say yes or no.

But you’re inviting them to a party that you take seriously, whether it’s a fiduciary board or advisory board. And if I were doing it, I’d start small. I’d have three. I wouldn’t want to have two. I’d want to have three. And I make them promises. We’re going to meet quarterly. We’re going to send you a packet of information before. We’re going to value your time, whether it’s virtual or in person. And I’m asking you for an annual renewal of commitment. And to me, if a person is taking it that seriously, and I like them, and I like their business, or I’m interested in their business, you shouldn’t have trouble finding people to participate on your board. That’s been my experience.

Liz Picarazzi:

And Mel, do you pay your board members?

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, we do pay our board members. We need to relook at that, by the way. We’ve not changed it in a long time. Every board of advisors I’m on is also paid. But Liz, when I say paid, some of these are very, very small. You know, a couple hundred bucks a meeting. They’re not significant. But I wouldn’t worry about the money. I would start with maybe they don’t get any compensation. And that’ll really test whether they’re interested, right? But we do pay our board members. Our stipend is $20,000 a year for our board members. And we wanted it to be enough to show we were serious, but none of these people are there because of the money. Because we’ve forgotten to pay them before and never got a phone call.

Loren Feldman:

Liz, you mentioned before the tariffs in China, and I want to dive into that a little bit. We talked about it a few months ago. I brought it up back then because Donald Trump was talking about his plans to increase the tariffs that he had imposed as President, if he is reelected as president. And in that conversation, you mentioned that Joe Biden could raise tariffs too, which at the time I didn’t think was much of a possibility. But he has since been talking about doing that as well. So both candidates for president are talking about this. I’m wondering how that’s hitting you and what your thoughts are at this point.

Liz Picarazzi:

It is probably my top preoccupation, to be honest. When Trump announced that he would impose a 60-percent tariff in January, we had already been kind of thinking that we needed to worry about that, just because of U.S. politics and what some of the polling numbers are showing. But like you said, in that podcast [episode] when we discussed it, maybe we didn’t really think that Biden would do that. Well, on a campaign in Pennsylvania on April 15th or so, he said that he was likely going to triple tariffs. The timeline on that—

Jay Goltz:

What does that mean? What are the tariffs now? What’s it starting at?

Liz Picarazzi:

So when I first started manufacturing in China, my tariff was 3 percent. Then, under the Trump tariffs, in 2020, went to 18 percent. Then it went down in 2021 to 11 percent. It’s been, since then, 11 percent. And then they’re talking about increasing it, tripling it. So it could go between 25 and 30 percent.

The last time the tariffs were put into effect, it was in like 30 to 45 days after they were announced. With these tariffs, apparently they are going to be going through Congressional review, which did not happen with the Trump tariffs. But I basically need to prepare for either a tariff under Trump or under Biden. And we’ve gotten the wheels in motion after the Trump declaration in January. We had been talking about Vietnam. We’re now working with our contract manufacturer in Shanghai that also has a Vietnam office. And we’ve got samples being made of a couple of our products in Vietnam.

And then Frank and I are going over there in two weeks to meet the factory, to check out the samples, to kind of get the lay of the land and have that as a Plan B. We really have to have a Plan B. We’d be stupid not to have a Plan B. And you know, I’ve got a lot of opinions about this, because I do think that these tariffs with China disproportionately affect consumers and small businesses. So some huge corporation, whether it be 5 percent or 25 percent, it’s kind of like an inconvenience or a nuisance. It’s not a showstopper. For a small business, it’s a showstopper.

Don’t forget, tariffs are taxes. If your personal taxes went from 3 percent to 18 percent to 11 percent and 25 percent in the span of just five years, how would you be able to run your household? I mean, it’s hard for me to run my business with that sort of volatility in the tariffs. So it’s really problematic.

And the other thing is, it’s not just about the money. It’s actually about my entire supply chain. So I’ve been over there in China now for seven years, and it’s taken me a long time to set up my supply chain, end to end. But there are a couple of points in this supply chain that I really wanted to highlight, and one of them is the engineering work that is being combined with production, all in the same factory, all with the same team, is incredibly beneficial to me. If I were to try to do that in the U.S., my costs would be incredibly insane. For me to have to move over to Vietnam and not know if I’m having the same level of engineering and production support, that change is a huge cost to my business and to my time and to my sanity.

So I’m very happy with the situation that I have with China right now. And maybe I’m a sample size of one, but I really like my factory. And I really like it that I have innovated my product line and I have expanded my business through this relationship with the factory that works really well for me. So that’s another thing I find offensive, besides just the schizophrenia in the tariffs, is that there’s a relationship here that has been formed between an American small business and a factory that happens to be in China that provides me the level of engineering and manufacturing services that, unfortunately, I was not able to get in the United States when I was here for three years in three different states: New York, Pennsylvania, Connecticut. I manufactured in all three states, and I wasn’t able to get what I needed in a profitable way. And also, there was a lot of frustration.

You and I’ve discussed on this podcast before, I never felt like American factories were hungry for my business. When I put out RFPs, I needed to literally chase them to get a response, to get a quote for what I needed. I’ve never encountered that in China. They’re hungry for my business. We work very well together. So these tariffs not only disrupt my financials, but it really disrupts my relationship that’s taken me seven years to build.

Jay Goltz:

I have to add, though, that some of this is just math. I mean, let’s say the worst-case scenario happened, and the tariff was 60 percent higher. That doesn’t mean you need to charge 60 percent more. If you marked up the stuff 20 percent more, it would cover the tariff. And it is a level playing field. Everyone else has the same problem. So everybody that you’re competing with is going to have the same problem. Just because it goes up 60 percent, that doesn’t mean that your sales price is going up 60 percent. So that’s what’s happened in America for the last 50 years with buying stuff from overseas. People are taking longer markups now because the stuff got so cheap. Well, in this case, it’s the other way around. And you could take less of a markup, but because it costs more, the gross profit dollars are exactly the same. So part of this is just pricing strategy.

Liz Picarazzi:

Right, but increasing prices by 24 percent with a city—I’m working a lot with municipalities now that it already feels like this might be too expensive—could make them decide, “You know what? We’re not going to move forward with this trash-containerization program.” Or, you know, developers of multifamily buildings: “You know what? Maybe this isn’t an amenity that we want to include in this anymore.” I mean, let’s not forget, my product is actually like 90 percent made of aluminum itself, which is being tariffed. So it’s not like I’m working with plastic or something. I’m actually manufacturing in the very material that is being taxed—not the most. At least I’m not in steel. I’m blessed. I’m in aluminum. But it would be very drastic.

Jay Goltz:

Yeah, trust me. I’m not saying it’s not a problem.

Loren Feldman:

Liz, Jay was making the point that there’s a level playing field and that the tariffs affect everybody making trash enclosures. But are you suggesting that there’s another alternative for your customers, that they just don’t have to buy trash enclosures?

Liz Picarazzi:

Yes, that might be the decision of: This is an innovation. This is something in the city that we want to do or something in this property we’re developing. It’s maybe viewed as somewhat discretionary and not something totally necessary. I haven’t presented any sort of price increases like that to my customers, but I’m pretty sure that they would notice that there was a 25-percent increase. Let’s say, I gave people a quote this year. The selling-time cycle is long for a lot of my customers. So if I give them a proposal this year for $10,000, and next year, I give them a proposal for $12,500, they’re going to notice that.

Jay Goltz:

They’re also going to know that tariffs have been raised by 60 percent. And you tell them, “Listen, unfortunately”—

Loren Feldman:

Jay, you keep saying 60 percent.

Jay Goltz:

I’m just using her number. That’s what she said.

Loren Feldman:

But not raising it 60 percent. Putting a 60-percent tariff on it.

Jay Goltz:

You mean, there’s already a tariff on it. Right.

Liz Picarazzi:

Right now, I have 11 percent. So I’d go from 11 percent to 60 percent. I have to push back on this. You can’t solve with your pricing math, Jay, on this. To go from 11 percent to 60 percent in the course of 60 days, which is about to happen if Trump wins. Because the last time he imposed tariffs, it didn’t go through Congress. It was an executive action that took effect within 30 to 45 days. My tariff rate went from 3 percent to 18 percent overnight.

Mel Gravely:

Liz, I’m with you on that. I don’t think you can—I think you’re dead on. It just feels this is the second time I’ve been on a podcast [episode] with you. And I can feel the emotion behind this. And so here’s my invitation. My invitation is: You’re already working on a Plan B. And, you know, there’s some emotional parts of working through what you’ve got in front of you: the relational pieces of it, how hard you’ve worked to get the supply chain intact. So I would like you to acknowledge that there’s some emotion to this, because spending more time on the emotion of it than you’re spending on the solution of it is probably not productive. It may be healthy. But I don’t know that it’s productive.

Liz Picarazzi:

I mean yeah, I may be really emotional about it. But I have like an eight-point action plan, Mel, to be honest.

Mel Gravely:

And I heard that too. I heard that too.

Liz Picarazzi:

I mean, even finding the very best lawyer to help me with an exception case this time around… The last time I did an exception I filed it by myself, which was really stupid. Of course, it was declined. I’m literally going to find the one that had the best results with exception cases when the tariffs were increased in 2018. And that’s going to be my lawyer. Like, I just started that hunt this week, because I don’t want just any old lawyer who says, “Oh, I can handle international trade cases.” I want people who did commerce, tariff law with China, and that’s where I’m gonna go with.

Jay Goltz:

I’m certainly not suggesting this is a simple solution. I’m just suggesting in the worst-case scenario, if you had to raise it because everyone else was raising it, that that’s better than losing money. And I don’t know, I’m guessing what your markup is, so I’m not even sure it’d be that severe. But that is worth doing the penciling, too, to just say, “Okay, what if?” Just to see, but I’m just suggesting. It’s not great, but it’s not like you’ve got to raise your prices 60 percent. It’s an option if you have no other options. And I certainly respect and appreciate you like the supplier and you want to stick with them. So this is complicated. And it does sound like you’re working on all pieces of it as you should be. So I just think pricing is one of the pieces.

Mel Gravely:

I just wonder, do you have the energy-slash-capacity to take another run at the United States?

Liz Picarazzi:

I am willing to do it. And interestingly, I only made that decision yesterday. Because I feel like if I don’t look into it, I will really not have done my homework. The last time I did this investigation was three years ago, and I came up with it was going to be about 67 percent more to reshore my work to the United States, which was bad enough. But the piece that I can’t get over is that I want a partner to be hungry for my business. I have not found any manufacturers in the U.S. that want my business.

Loren Feldman:

Liz, you were a smaller business back then. Especially if the tariffs come into play and do increase, you would be looking to spend more money with an American manufacturer if you did reshore. Do you think it’s possible that you might get better service at that higher price, with more business?

Liz Picarazzi:

Yeah, I think it’s definitely possible, and I am going to look into it. There were a couple of manufacturers in the tri-state area that I found that I thought, “Well, I could work with them.” But the price was just still too high to deal with, at that point. I can kind of go back to them. But a lot of it goes back to, you know, this sounds ridiculous, but I feel like I have this—not loyalty—but I like the energy. And I love being an entrepreneur, working with a factory that can literally turn around an idea into a prototype in 48 hours. And it’s happened over and over with my factory. I don’t know if I’m going to find that here. That was part of the reason I moved it over there.

Jay Goltz:

I deal with it with buying picture-frame molding. The reality is, even if you had to pay a 60-percent tariff on the Chinese price, it still might be cheaper than buying in America. I buy mostly from Italy and Spain, but when you look at some of the prices of whatever. You go to the store, and you buy a garbage can, you think, “Wow, it’s only X dollars.” This stuff is super cheap coming from China. So even with the tariffs on there, it still might be cheaper to pay the tariffs than try to get it made—well, you should try to get it made in America. But it still might be cheaper than getting it in America. That’s just the harsh reality.

Liz Picarazzi:

Yep. Well, I mean, that’s the math that I’m going to do.

Mel Gravely:

Well, I encourage you to try it. And the only reason I say that is, first, I think it might be a quality of life improvement to have a U.S. base. But there’s a manufacturer in this country that will be a wonderful partner to you. I don’t know where they are, but our country is big enough that I bet there is. And it may be like changing your doctor. You know, the last one, you loved them, but they retired. And now you’ve got to find a new one. But you’ve got to orient them enough to understand what you like and how you are and what your background is. There’s got to be a manufacturer in this country that would love to work with you. Now, the question about price is different.

Loren Feldman:

Liz, you have plans to go to Vietnam, right?

Liz Picarazzi:

Yes, we are going in two weeks. We’re going to go for about a week. We have samples that have already been made. And we’re going to be checking them out. And if all goes according to plan, then we’re going to do a small- to medium-sized production run in Vietnam while maintaining production in China, and then kind of figure out: What are the proportions? So this may be a little bit about balancing risk—balancing risk between China and Vietnam.

Because there’s also a risk in having all production in one place. And so as much as I say, “I like my Chinese factory,” for these years that I’ve been there, it’s actually been sort of risky that I don’t really have a Plan B. And that’s partly what doing some work in the U.S. was about. It was diversifying that risk.

Jay Goltz:

When they talk about tariffs, is it just China? Or are they possibly going to stick it on Vietnam, too?

Liz Picarazzi:

Well, there’s tariffs on everything that comes in. So if I were to bring it in from Vietnam, it would still be 3 to 3.5 percent. But, you know, it wouldn’t be at 25 percent.

Jay Goltz:

I have to say, just anecdotally, going to Nordstrom looking at where the clothes are made, I have to tell you, it was like all China a few years ago. And I have noticed now there’s lots of Vietnam, lots of Pakistan. It does seem to be other places that are manufacturing stuff that’s getting into the American market instead of just China. I think plenty of companies are trying to do what you’re trying to do, and succeeding.

Mel Gravely:

Here’s what’s absolutely certain: Our relationship with China is not going to get better over the next decade or two. And I don’t know what that means to our businesses, but the crystal ball says we’re headed to a bad place with China.

Loren Feldman:

Mel, do you buy anything from China for your construction business?

Mel Gravely:

Yeah, of course we do, but I’m buying it through others to get there. And so we don’t tend to have big challenges there, and we will pass all of it through. So we don’t have the same volatility. We will pass 100 percent of the cost through, and if customers don’t want to build it because their steel costs too much, then they won’t build it. It’ll be okay. So I’m not speaking from a guy who gets impacted by it. I’m just saying, if you just look at our relations with China, they’re not improving as a nation. So you’ve gotta have a Plan B.

Jay Goltz:

You don’t need a crystal ball then. I had a couple of vendors in China. They’re done. We’re not buying from them. They just stopped producing picture-frame molding. So we’re pretty much done with buying from China. It just shut off one day. So I think there’s plenty of businesses out there that used to get stuff from China that aren’t anymore.

Loren Feldman:

Liz, have a great trip to Vietnam. We will be very eager to hear what happens there, what you think, how it goes. In the meantime, my thanks to Jay Goltz, Mel Gravely, Liz Picarazzi—and to our sponsor, the Great Game of Business, which helps businesses use an open-book management system to build healthier companies. You can learn more at greatgame.com. Thanks, everybody.