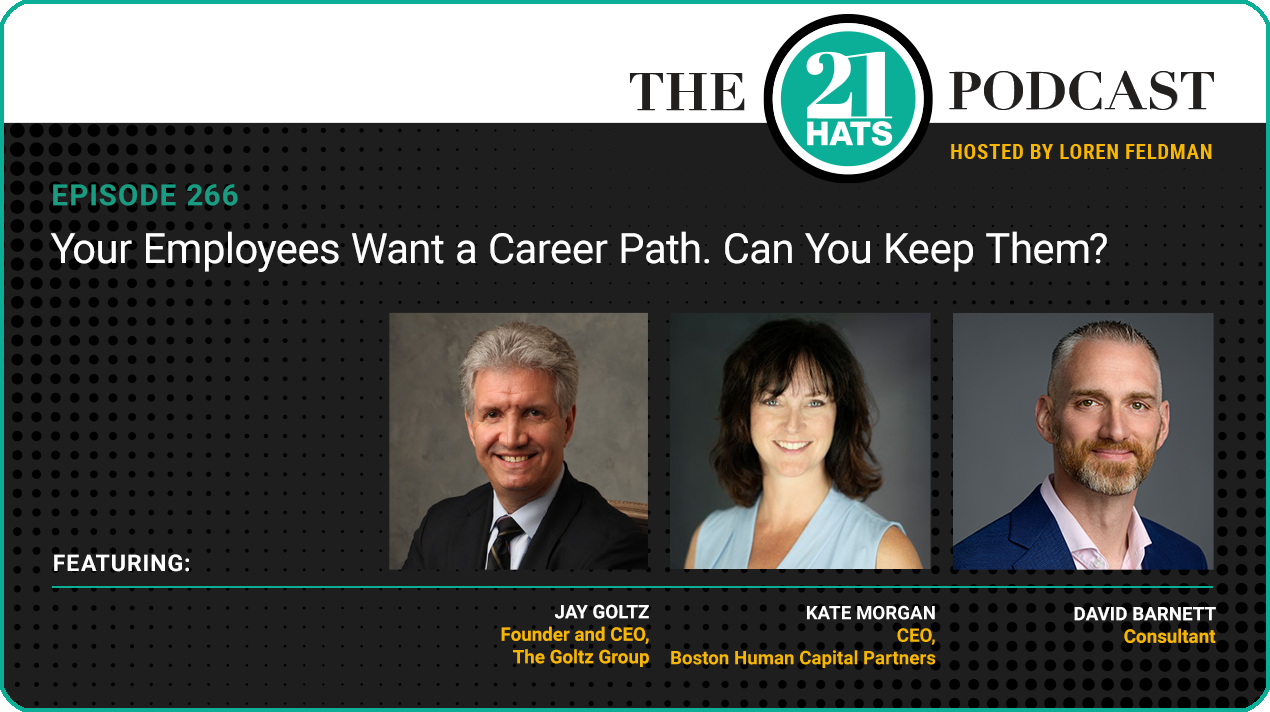

Your Employees Want a Career Path. Can You Keep Them?

Introduction:

This week, David C. Barnett, Jay Goltz, and Kate Morgan wrestle with one of the trickiest challenges for business owners: how to give employees room to grow without losing sight of the company’s mission. David points out that every business is on its way to obsolescence unless it deliberately evolves—and one way to do that, he says, is by letting employees experiment and try new things. That approach, Jay says, is exactly what led to his building a furniture business. Plus: Kate and Jay agree that while many aspects of running a business can be stressful, nothing has been more stressful for them than the period when their businesses were growing the fastest. And the owners react to a Reddit post from someone who has found that hiring employees has created more problems than it has solved. “Is this just what having employees is like?” the owner writes. “Please tell me I’m not the only one losing my mind.”

— Loren Feldman

Guests:

David C. Barnett helps people buy and sell businesses.

Jay Goltz is CEO of The Goltz Group.

Kate Morgan is CEO of Boston Human Capital Partners.

Producer:

Jess Thoubboron is founder of Blank Word.

Full Episode Transcript:

Loren Feldman:

Welcome, David, Kate, and Jay. It’s great to have all of you here. We’re now in the fourth quarter of what has been a year full of surprises, some of them better than others. And as the hits keep coming, I’d like to ask each of you how you’ve been affected, if at all, by some recent developments. So, for example, the U.S. government has shut down. I should say we’re recording this on Friday, October 3. As of now, the government has shut down. President Trump has announced a new round of tariffs, including on kitchen cabinets and furniture, and the President has also sent the military into Chicago as part of his crackdown on immigration. A couple of those things seem aimed right at you, Jay. Are you feeling any impact?

Jay Goltz:

[Sigh] First of all, it was in the paper today: Travel to Chicago, tourism, was at a record high last year. This whole thing is just a complete—calling Chicago a “hellhole” is just ridiculous. Not that there aren’t too many murders here, but— Anyway, no, that hasn’t affected me.

The tariffs, they keep moving all over—could have an effect on me. I’m, frankly, just kind of getting numb to the whole thing. You know, there’s intellectual and there’s emotional. Intellectually, it’s frustrating. Emotionally, you just have to—at least, I know, myself—dig in and just deal with it, because we’re in a difficult time right now. But I’m gonna get through it just like I have the other 10 times.

Loren Feldman:

I mean, I know you’ve been affected by tariffs previously. You import framing from Europe, and I guess furniture has been affected to some extent, depending on where it’s coming from. But now there’s an industry-specific tariff that I think is going to start at 10 percent, and then there’s 25 percent on kitchen cabinets, which I think, based on what you’ve told us, could affect you, because it’s part of the whole housing thing. People aren’t moving, so they’re not framing stuff as much. They’re not buying furniture as much. This doesn’t seem likely to help. Have you looked at your cost structure and thought about how much of that—

Jay Goltz:

Well, the number right now is 15 percent. Okay, so if I have to figure that out and build it in, I’ll do it. This is a whole new phenomenon. I’ve lived through recessions. I lived through September 11. The ’08 meltdown was horrible. This is a case of—and I know Lou Mosca has talked about this—at some point, you have to say to yourself, “I’m going to deal with what I can fix and just ride out the rest of it.”

Loren Feldman:

Well, let me stop you there, because this is something that you do have to deal with. I think the upholstered furniture—do you import a lot of upholstered furniture?

Jay Goltz:

Well, coincidentally, we import furniture, but the upholstered furniture, no, comes from North Carolina. I mean, I don’t—

Loren Feldman:

Oh. Well, that’s a break.

Jay Goltz:

Yeah, it’s complicated. I’ve got so many balls up in the air right now between the business being off. And I mean, it’s a question of: What dials can I turn? Okay, I can definitely adjust the pricing a little bit. But I’ve got my hands full with other stuff, like business is down. My big breakthrough was, I realized I really don’t need as much space as I have, and I’m subletting some of my buildings—and for big money, which isn’t a little fix.

This is a big fix. Like, I’m going to free up 20,000 feet of space, and so I’m going to make it back. So it’s a big picture thing of: Okay, if your cost of goods sold goes up a little bit, can I make it up somewhere else? And in my case, I’m going to get my rent expense down. That’s one thing I can do.

David Barnett:

Loren, I want to comment on your comment there. When Jay said he bought his upholstered furniture from North Carolina, you kind of said, “Oh, well, that’s good,” as though the tariffs wouldn’t affect it, but it will. Because it doesn’t matter where Jay buys his furniture. As soon as foreign competitors have the price increased by 10 or 15 percent, it means that domestic manufacturers are then free to increase their prices, too. And this is what was seen with aluminum and steel and all the other commodities that have had these sectoral tariffs. As soon as imported goods have the tariff applied, then the domestic producers are free to raise the prices, too.

Loren Feldman:

That is a great point, and it’s even more than 15 percent. The upholstered furniture is scheduled to go up to 30 percent now, as of January 1. So that is looming, although I think there may be some reason for Jay to hope that the domestic people won’t go all the way.

Jay Goltz:

What you said is true. It’s just in my particular case, we sell better stuff. I’m not selling Chinese sofas for $399, so I don’t think it’s going to affect me as much as it’s going to affect some of these people who sell the low-end stuff. But what you said is absolutely true. I just think I’ve got a little protection there. And a lot of the upholstered stuff we sell is custom, and that’s not coming from overseas. It’s a messed up time at the moment to be in business. No question.

Loren Feldman:

What about the military stuff in Chicago, Jay? I’ve seen video of people on the streets. You’re a retailer. Do you think it’s changing the vibe on the street at this point?

Jay Goltz:

It’s horrifying. And the stories are endless. People who have been here for 20-30 years getting scooped up. I don’t know that it’s affected business. I’m not downtown, but it’s definitely made everybody upset. Or not everybody, but many people are very upset about it. And the theater of it, the, “Oh, we’re only looking for criminals.” It’s certainly not true. It’s a horrendous situation, just a horrendous situation.

And at the same time, the fact is, I don’t have to be an economist to know this: If, quote-unquote, all of the people who were here who are undocumented left, it would force this country into a depression. Because they buy stuff, they rent apartments, they buy cars. You can’t take millions—whatever the number is at this point—out of a society and not have the GNP go down! It’s a mess, and I’m not an economist, and I’m not in a news show. All I can do is deal with my little microcosm of what I’m dealing with. And I really have to mentally tell myself that.

Loren Feldman:

Kate, obviously, with your business, you would not be affected directly by tariffs, for example. But are you seeing ripple effects from any of this?

Kate Morgan:

It’s so bizarre, because for the last three years, it has been a bloodbath in software. And I mean, we got hammered. Well, fast forward three years, and you have to remember that the majority of our clients are VC-backed startups, and so when we saw the layoffs from big tech in 2022, that was where the ripple effect happened. Everybody went into vanity layoffs. They were just doing whatever they could to hold on to their working capital. And the VCs were brutal. They were saying, “You have to figure out how you’re going to get to product-market fit. We’re not giving you any more money. Blah, blah, blah.” A lot of startups collapsed.

Well, now we’re seeing all these VCs, they sat on their money for three years, and their LPs are like, “Hey, we gave you this money, and we’re all talking about AI. When are you going to start investing?” And so we are actually seeing a huge increase that we haven’t seen in three years. Like, I actually feel pretty confident. I just hired a person. I was thinking about hiring a second person, but we decided to kind of hold off. But yeah, it’s very weird. I do see when we look at the overarching concern with immigration, a lot of software engineers, they come over for their Masters, and then they stay here. And there’s quite a bit of confusion on how they’re going to process this. And of course, there was some talk about having a $100,000 fee to process an H1B [visa]. That’s not going to go anywhere.

Loren Feldman:

That’s not going to happen?

Kate Morgan:

No.

Jay Goltz:

Don’t you think in some cases, the companies will, in fact, pay the 100 grand and tell the employee, “All right, here’s the deal. We’re gonna pay you less for five years and we’re gonna”—don’t you think somebody’s gonna do that?

Kate Morgan:

No, no, it’s just too complicated.

Loren Feldman:

Wait, what are you saying? Are you saying, Kate, that companies won’t pay that fee?

Kate Morgan:

Well, it doesn’t apply right now. And they may want to try to apply it to H1B lottery approvals going forward, but it’s going to be heavily litigated, and it may never go into effect.

Jay Goltz:

I’ll tell you one thing that’s been interesting. I can’t think of one person who’s quit in the last year. I mean, this job-hugging thing is real. I think that people are afraid to leave the job. And I usually have a very low turnover as it is, but it’s zero. I’ve got 110 employees: zero. I mean, that’s interesting. Usually, it would have been a couple of people.

Kate Morgan:

Yeah, I would agree. But now, again, we’re starting to see people picking their heads up and looking around, just because, again, for our industry, everybody’s just so hunkered down for the past three years, they’re kind of itching to do something new. And we’re doing it with lower salaries than they’re currently at for equity.

Loren Feldman:

Your clients are able to hire people with lower salaries than they have been in recent times, but they’re giving up more equity?

Kate Morgan:

Yeah, yeah. I’m working with a really early-stage startup right now. The founders had previously some really big successes. And I’m talking to a candidate for them who was making over $300k with his bonus. And I’m talking to him about a $200k salary with substantial equity. But you know, he’s feeling good. He’s really interested in it.

Loren Feldman:

Dave, how about you? You’re in Canada, so it’s unlikely, you would think, that you’d be directly affected by the U.S. government shutting down, but that means the SBA is shut down and not making loans for acquisitions. I know you have clients here. Is that affecting you?

David Barnett:

Well, not yet. I mean, it’s just today, right? I mean, it’s just brand new. And honestly, there’s all kinds of reasons why deal closings get delayed by days or weeks anyway. The last time this happened, it didn’t really start to have a serious impact until it had dragged on for quite some time. And I’m thinking of the time back during the lockdowns in 2020 when the SBA basically stopped processing new loans in favor of doing all the Covid-relief programs that they were managing. And so things got delayed by a little while.

So it’s really going to come down to, I think, how long it lasts, if it’s going to create a serious backlog. I know that one of the things I saw here in the local news was for travelers: Would there be increasing lineups at ports of entry for people trying to cross the border and things of that nature? And again, we’ll have to see if people are going to show up to their jobs, wondering if they’ll get paid eventually, I guess.

Jay Goltz:

What about being in Canada? I know Canadians who refuse to come to America now, given the circumstances. Florida, I think, has gotten hurt a lot, that a lot of Canadians go to Florida in the winter, and from what I’m told, it’s cut back dramatically. Have you seen that, being a Canadian?

David Barnett:

Yeah, I mean, I know plenty of people who used to spend their whole winter down there who are not going this year. The tourism season in Canada has been absolutely gangbusters. So many people who would normally have traveled to other places are staying here, and we’re seeing it in the data that I see in the news. I mean, I’m not directly involved with tourism, but the people that I know who are are saying they’re having a really great time in the headlines.

But then, I was at a conference yesterday and today where somebody was sharing that certain categories of, call it discretionary spending, like restaurants, bars, etc., where amongst their clients, they were seeing more and more trouble, which kind of speaks to an overall decline in economic activity anyway. And I think it’s easy to attach a lot of what we see to the headlines, the political news, what is happening with the President and all these kinds of things. But I think the economy on both sides was starting to slow down before the year started, and we’re slowly starting to see that unfold.

Jay Goltz:

It’s always a mixed bag, but the one piece I would put into every discussion at this point is the Baby Boomer thing. The fact is, every single day, 10,000 Baby Boomers are retiring, and that’s affected a lot of stuff. And in picture framing, for instance, it sounds silly, but the fact is, people eventually stop framing pictures because they’re downsizing and they don’t have any space to put the stuff. The framing industry peaked in 2000, and as people get older, they stop spending money on a lot of stuff.

Kate Morgan:

I was just watching something on the news that Gen Z, they’re not dating as much because the cost to go out to have dinner is just so expensive. So, yeah, it’s just kind of fascinating.

Jay Goltz:

They’re not drinking either, from what I’ve read.

Kate Morgan:

They do not drink, which, actually, I really appreciate my team being kind of alcohol-free. It’s making my budget go a lot farther.

Loren Feldman:

Jay, talking about all of that, I’m curious, have you rethought your advertising or marketing budget? Are you still spending money the way you were previously?

Jay Goltz:

No, I’ve cut back. We’re still doing the online stuff, the social media, which is beyond me, but just the same old. You know, I’ve got three framing locations. I decided, “You know what? I’m gonna go back on the radio.” It worked years ago. I put, I don’t know, 30,000 or 40,000 bucks into it—

Loren Feldman:

This year?

Jay Goltz:

Yeah, and now attribution is always a problem, but I am in a unique business in that you’re in my computer. So it’s not like you’re just coming in, buying something, and leaving. So when you walk in with framing, we know whether you’ve been there before, because if you’re not in the computer, we say, “Oh, you’re not in our computer. Is this your first time here?” “Yes.” So then we say, “Oh, where did you hear about us?”

And you know, there’s only several buckets. One is, “My friend sent me in.” Okay, that one’s pretty clean and accurate. Drive by, the internet, social media. The fact of the matter is, almost nobody said, “Oh, I heard it on the radio,” which kind of just—when I say almost nobody, I mean, after three months, three people, or something. And now the problem is, maybe they’ve driven by it 100 times, and the radio ad pushed them over the edge. And they said, “Oh, I drove by.”

So it’s not perfect, but when you spend that kind of money, I’d like to get 10 people who said that, and they didn’t. So I’m done with that. I’m not doing any traditional advertising. I used to do ads in magazines. I used to do direct mail. I’m basically counting on my location, counting on my internet site, counting on social media. Though, even the social media thing’s a big question mark, like extremely hard to find attribution with that. So it’s a very different world than it was 20 years ago. So at the moment, I pretty much cut back my advertising budget.

Loren Feldman:

David, are you doing anything different?

David Barnett:

I’m making more of an attempt to be live in front of people. I mean, that’s where I was this morning. I was at that conference of lenders and talking with them about the things we do and how we help clients and everything. And over the past—well, actually, since August, I’ve been to four different conferences. Two of them are down in the States, and just trying to get out in front of people, sort of access different channels of having people meet me.

I try to get onto podcasts and things as a guest, to meet new audiences, and talk about this kind of stuff and LinkedIn, of course. But I think, really, this year, the thing I’ve done differently is try to get into more events where I’m out shaking hands and being one of the very few people who have business cards anymore to hand to people. [Laughter]

Jay Goltz:

Ugh. That is a sore subject for me. I meet these people, and I think, “Seriously? You can’t print them? Really?” And they go, “Oh, no one uses them.” Really? No one’s using business cards anymore? I’m just fascinated—for $30.

Kate Morgan:

Jay, you’re dating yourself.

Jay Goltz:

So my point is, I’m not the only one who’s still alive, who’s still doing business. Even if I’m 80-percent wrong, 20 percent of the people would like to have a business card. So for that 20 percent—even if it’s 10 percent—really? You can’t print some business cards for $40? Sorry, I’m not giving up on that one.

Kate Morgan:

I just use my phone and connect with them on LinkedIn.

Jay Goltz:

I’m sure you do, but like I said, I’m not 107. There’s still plenty of 69-year-olds still in business. So until we’re all dead—I’ll send a notice when I’m dead. You can then stop printing business cards. But until then, like, maybe do it for another 5-10 years?

David Barnett:

The problem I have—because I’ll meet people who have these fancy QR things on their phone, and they’ll say, “Scan this.” And I scan it, and it’ll create a new contact in my phone. And then I think to myself: How will I ever find this person? There’s a thousand people in there. And on my business card, on the front side, it’s got your contact details, but I put the LinkedIn QR code on the back side. And so if people are more digital, I just flip it over. And I say, “Well, scan this for my LinkedIn.”

But what I always do with business cards when I collect them is, I might make little notes on them. And that evening, when I get back to the hotel room, I go through them. I sort them, I maybe send emails to people, or follow-ups. And I find that it’s much easier for me to organize myself and try to do something with those connections if I have those little cards that I can sort out.

Jay Goltz:

And the real question is: And why wouldn’t they give you a card? Even if 90 percent of people don’t. Like, you got a card, you stick it on your desk, you look at it for a couple weeks: “Oh yeah, that’s that guy. I’ve got to call him.” Like, why wouldn’t you do that? is my question. I mean, it doesn’t make any sense.

Loren Feldman:

Dave, I don’t think you know how happy you are making Jay this morning. I hope you appreciate that. And if you just tell him now that you love fax machines, too. [Laughter]

Jay Goltz:

All right, I’m off of fax. I never was on. He’s exaggerating, but no, the business cards, for sure.

Loren Feldman:

Back to 2025.

Jay Goltz:

Are we still in 2025? I’m already in ‘26. That’s how advanced I am. [Laughter]

Loren Feldman:

It’s gonna go on a little bit longer. Dave, you mentioned that you were at this conference of lenders. What was the mood like there? What were people talking about?

David Barnett:

It was interesting. There were a lot of, you know, sort of veterans there, and a lot of younger people there. And a lot of the talk was from veterans telling the younger people about what it’s going to be like as we get into a downturn. A lot of people in the room had not been through a full business cycle, and so they had a lot of different speakers who came in. There was an economist from Equifax that came in to talk about the data they’re collecting through the credit reporting that those guys do with credit reports and whatnot. There were some people from the bankruptcy and receivership industry talking about some of the stuff that they were doing. I was there to talk about equipment evaluation and calculating goodwill in small businesses for transactions and lending.

And there were a lot of stories shared about problems and things that these different lenders were seeing pop up in their accounts. So it was very interesting, and I learned a new term. So amongst this group of people, they have a term: a “business tourist.” What a business tourist is, is somebody who is not a business person but has somehow ended up owning a business—like the dentist who buys the pizzeria. And this is sort of the canary in the coal mine amongst their business files. These particular kinds of owners are the ones who are maybe having the most trouble right now.

Jay Goltz:

Well, I have a new term that I just came up with for these people who I get emails from literally every single day. I get two or three, and I’m calling them “stupid asses.” [Laughter] This is what they do. They send you an email that says—they all say the same thing—“We can lend you money as low as 1 percent a month, blah, blah blah.” And then they just sign it “John,” and then it’ll say some name underneath it, business loaning, blah, blah blah. But the email address doesn’t match that, and I don’t know why, but almost every single time their email doesn’t even match the name of the company they sign off on. And I’m thinking: Why would you call?

First of all, there’s no phone number. There never is. But why would you even email back to these people? They’re like marketing companies or something. But I don’t understand why almost never does the email match what the signature is, and they must send out 8 million of these a day. And I don’t know, did anybody respond? Somebody must respond, but I get literally two or three a day.

David Barnett:

Wow.

Kate Morgan:

Yeah, same here.

Jay Goltz:

Do you have an explanation why the email doesn’t match the name? I thought maybe because they’re marketing.

Kate Morgan:

It’s probably lead-gen companies.

David Barnett:

That’s what I think, yeah.

Loren Feldman:

All right, so David and Kate, you guys are fairly new to this podcast, although you’ve been around most of this year, but I haven’t done with you what I’ve done with pretty much everybody else—certainly with Jay—which is—

Jay Goltz:

Torture them? [Laughter]

Loren Feldman:

Yeah, exactly, torture them by asking you to talk about the biggest mistakes you’ve made in business. And I want to give you the same opportunity. So Kate, maybe starting with you, would you be willing to share with us what your biggest mistake has been?

Kate Morgan:

Yeah, I know you’re probably expecting me to say something like a bad investment or a disastrous hire, or some sort of strategy that’s gone off the rails. But honestly, my biggest mistake was how I handled my own mental health. When I launched my business, my company was growing at an incredible rate, and I was four years in and scaling super fast. I treated myself kind of like an unlimited resource. So when I got hit with a potential lawsuit, it really rocked me. And I remember, like, what do we do when we have a problem? Well, at least for me, I called my father for support, and his response was, “Well, that’s why you get paid the big bucks.” Not exactly comforting.

Jay Goltz:

It’s funny you say that because my father called me once. I was having a real bad day. And he said, “How are things going?” I said, “Oh, you know what? I just had to fire a guy. He’s got two kids. I feel bad.” And he just said, “Well, you know, people want a job, but they don’t want to work.” It was like a throwaway line, and that was the last time I talked to him about business. So I know that feeling of, you were looking for some great wisdom, and it was really out of his wheelhouse. And I, in hindsight, recognize that now, but it was a disappointing day. But I totally feel your pain on that one.

Kate Morgan:

I appreciate it. Well, I can tell you, the stress and anxiety at that time was pretty crushing. I went to a doctor who was very quick—too quick, I think—to ply me with pharmaceuticals. Of course, hoping for a quick fix, I jumped at it. After all, he’s a doctor. And when you’re under mental duress like that, I mean, it was sort of like taking Tylenol for a broken leg. So it didn’t fix me. It wasn’t like I was all Benzoed up or something like that. But it dulled me. My drive wanes. But worse, my creativity vanished. And for me, creativity is what I believe separates business owners from entrepreneurs.

Jay Goltz:

So wait, here’s the interesting part for me, because I totally identify with everything you’re saying. My question is, it doesn’t sound to me like you had—you’ve tried your father, but we’re all freaks. The fact that our fathers—we think should know better than us. It’s not the case. The question is, did you not have another business person you knew who was a little bit of a mentor, who you could call up, and who would say to you, “Hey, this is what happens in business”?

I didn’t. And as a result, I was stressed out, just like you were. And I also went to the doctor, except this was 40 years ago, before the whole thing with everybody’s taking medication for stuff. He gave me muscle relaxants because I said I had horrible pains in my stomach, and the very next day, I coincidentally read that stress causes terrible stomach—and that’s exactly what it was. And he didn’t know to tell me that. I figured out it was stress. So did you not have anybody you could call to walk you off the ledge?

Kate Morgan:

I eventually got there, because I did eventually join EO, which was super helpful. But I was in that fog for two years. And that first year, my revenue dropped 10 percent. The next, another 11 percent. And I think we can all say numbers always tell a story, and it was really screaming for change. And so I ditched the meds. I rebuilt on mindfulness, holistic practices, less wine, and dropped caffeine like 100 percent.

Loren Feldman:

Did you figure out those steps all on your own, Kate?

Kate Morgan:

Yeah, it was, I mean, it was a lot of self-reflection, because I was like, “Why am I dropping so much revenue?” There was no reason, aside from me just not feeling it. So I really had to pick myself up by the bootstraps. I will say that my forum from EO really helped make me feel a little bit more grounded to be able to push forward.

Jay Goltz:

Were you working out at all?

Kate Morgan:

Yeah. Oh yeah, I’m a big runner.

Jay Goltz:

I’ve got to tell you, you just described why I do this podcast. Because I feel bad for all the entrepreneurs out there who are on their own, who are stressed out, who are trying to figure this out. And I had nobody to go to, and you had nobody to go to. And I did join groups, and that helped. But people need somebody to talk to, like to help them understand, “Hey, this is what we signed up for. But there’s ways of fixing this.” I will tell you—I wouldn’t have told you this 20 years ago—I truly believe working out is a critical piece of this, that I feel much better when I work out, and I can handle it better. And I wasn’t. I was just stressed out all day long.

And I feel bad for all those people in the world who are on their own trying to figure this out, because in other quote-unquote professions—whether you’re an accountant, a lawyer—you’ve got people who are older than you, who are going to help you. You’re in business for yourself. You’re by yourself. And that’s why I do this podcast. And thank you for being on this podcast. Thank you, both of you, because I believe—and Loren, thank you—I believe we’re doing good for people who are out there trying to figure out how to navigate this, because it’s not easy, but it is fixable.

Kate Morgan:

Yeah, Jay, you’re so spot on. So I can tell you, I modeled my business after a company I worked for that was wildly successful. The two founders did amazing before the dotcom/telecom implosion and then 9/11. But when that company crashed, when all that went down, the two founders eventually drank and drugged themselves to death.

David Barnett:

Wow.

Loren Feldman:

But you know what’s interesting? I mean, that’s awful, obviously. But what I find interesting about your story, Kate, and yours, Jay, is that the stress hit you at a time when your business was growing dramatically.

Jay Goltz:

Like crazy. 30 percent.

Loren Feldman:

And that’s what everybody thinks they want. And you know, it’s just so interesting that that kind of success can produce that kind of stress.

Kate Morgan:

Well, if you think about it, only 4 percent of companies get over a million dollars, on average. That’s it, 4 percent. So when you’re getting over two, two and a half, 3 million, you can kind of feel like you’re a little bit at the end of your abilities. And you have to figure out how to structure things.

And even when I got out of that fog, I brought in my business coach. And that following year, we grew 27 percent. So I think you really have to, as Jay was saying, surround yourself with people so that you can feel a little bit more grounded, have some guidance. Just have that hand on your back so you don’t feel so alone.

Jay Goltz:

I literally, and I’m telling you literally, was lying on the floor at home. I could not get up. And I always thought people who did that were exaggerating. I went to the hospital in an ambulance because my neighbor was a doctor, and he goes, “Oh, you better go to the hospital.” It was absolutely 100-percent stress.

I had a key guy working for me who I needed to fire. It was the first time I ever went through that. I was worn out. And it was 100 percent because of that, in hindsight. And I have never had anything—I have never had a back problem since. It was 100 percent stress brought on by not knowing how to deal with stuff. And it’s brutal. And I will tell you—I want to tell everyone this—I had a customer once tell me, “Jay, the bigger you get, the harder it gets.” Bullshit. Bullshit with a capital B. It is much easier when you start to figure out how to do this, and you can figure out how to do this. I’m not stressed. I haven’t been stressed out in, I don’t know, 20-30 years.

Loren Feldman:

You’re not thinking clearly, Jay.

Jay Goltz:

Yeah, it’s not that I don’t have some pressure now. Trust me, I do. But I am nothing like when I was 32, and I had three kids, and I was trying to get it to all work. I had to grow into it. And I tell people: If you’ve been in business three, four, or five years, you’re still a newbie. This takes a while to get the sea legs to deal with it, and if you stick at it, you will get there.

Kate Morgan:

Yeah, yeah.

Loren Feldman:

Thank you for sharing that, Kate. David, how about you?

David Barnett:

Yeah, I think that the biggest mistake I’ve made in business is not thinking about the career path of employees. So, when things started to grow for me—when you go from being sort of a solo person to adding that first helper—I had in my mind a certain role and qualifications that would be required. And I found someone to fill that. And the problem, the mistake I made, was I did not see the path forward for that person, because they had the ability to grow and develop and do more than what they were doing for me. And I think in failing to create that path for them, what I did is, I probably created a realization in them that if they were going to get ahead and earn more money and do more with their career that they were gonna have to leave. And that’s what happened.

And I realized later, “Hey, I could have had them do this and that, and this and that.” And I would have been paying them more, and then we could have grown more quickly, I think, and then added another person to sort of backfill them. And so, that, I think, is one of the mistakes that kind of set me back a little while. And then when I hired again, I was very much more cognizant of this aspect of business. Now we’re a team of five, and I think about it every year. When we do our annual planning, I think about how I can see people developing and growing, and how I might help them grow with me. Because it sucks to start off with someone new. It takes a long time for the new person to learn what they’re supposed to be doing and learn about your business and all that kind of stuff. All those stats about turnover being expensive are absolutely correct.

Jay Goltz:

So in your case, it’s also partially about—which is the same I’ve had—looking at your business model: So this person’s talented and good at it. Gee, I can charge more for that. Or we can start offering these services. When you say “career path,” that’s basically looking at your business model and going, “Wow, I can build a company around people who have this kind of talent.”

Because that’s exactly what I did. I didn’t wake up one day and say, “Hey, I think I’m going to get into the furniture business.” I hired someone for nothing. She was a $14-an-hour-or-something kid. She turned out to be extremely gifted at this thing, and I built a multimillion-dollar furniture store because I recognized she was talented. And I kept her around for 20-some years. That was one of the mistakes I didn’t make. You know, I made every other one.

Kate Morgan:

It’s hard, though, when you’re building a business. And because of the startups I work with, I ask them, “Your job description is going to be the pain point for today, but you need to start thinking about: What does success look like 12 to 18 months out for this person?” Because they have to be thinking about evolving that resource. So yeah, I think a lot of companies have challenges with that, particularly when we had just the Wild West of hiring. Nobody was thinking ahead. And I feel bad, because I think the younger generations kind of got hammered about how there was no loyalty—they were all about entitlement, they wanted raises, all this. They just wanted some inclination of where they were going to go.

Jay Goltz:

You just said it: It’s hard, but it’s doable. That’s the point. It is hard, but there’s no question, once you figure out what you’re doing, this is all doable.

Loren Feldman:

Well, are you sure about that, Jay? I can imagine a lot of business owners listening to this and thinking: I run a small business. This is what I do. I can’t be inventing all different kinds of things to try to keep my people happy. I run this kind of business. If it works for you, great. If not, then we’re going to have to move on. How hard was it for you to develop that path that you decided you wanted to develop?

Jay Goltz:

It gets back to knowing yourself. Do you have the mentality to grow with this? And some people don’t, and that’s okay. The smartest thing one guy once said to me—he was older than me. He was about 50-something. I was 30-something. He said, “Jay, everybody knows at some point in their life, they’ve got limitations. It usually hits you when you’re 50.” And I said to myself, as a 32-year-old, “That’s pathetic.” And then I hit 50, and I realized he’s right. I don’t have the mentality to build a $100 million company. I just don’t, and it’s okay. And it comes down to knowing yourself.

David Barnett:

My answer is that—and this is what I tell people who want to buy a business. I warn them that all businesses are on the path to obsolescence, because the world around us is changing all the time. And the way business was done in any industry 15 years ago is not how it’s being done today. And so there has to be some kind of evolution and iteration happening all the time in every business to avoid falling behind the curve—unless you’re going to be someone who’s literally going to allow your business to slowly fade away over a decade or so and then just shut it down when you’re not making any money anymore.

You’ve got to have some degree of creativity in trying and experimenting with new things. And you know, in Jay’s example, he saw a door open with a pathway that led down the furniture road, and probably thought, “Hey, this aligns with the framing.” You know, people are decorating. And so it would make sense to me. And you know, once you owned the real estate, you then had some kind of commitment to be able to take advantage of the space you had.

Jay Goltz:

Boy, you are so smart. Really, that is truly the key to the whole thing, is that I was able to buy the right real estate. And that was why the whole thing started to work. I call it connected by design—a little double-meaning there. Very smart. Thanks for being on today. [Laughter] Really. No, that was really, that was really smart of you to figure that’s exactly what happened. I figured out: I’m in the home-furnishing industry. I could buy the building. And that’s what drove the whole thing.

Loren Feldman:

All right, we only have a couple of minutes left. As you guys know, I sometimes like to throw kind of a case study situation at you, drawn from a question that I’ve read on the small business subreddit. So I picked out one for today. It actually kind of relates to what you were just saying, Dave, about the mistake that you made. Let me read this to you. An owner writes:

“I don’t even know what to do anymore. We went from a small team of three to eight since April. And I thought hiring would solve problems, but really it just created new ones. Like now, instead of being stressed about delivering, I’m stressed about training people to do the work. We had this new guy just joining. Seems smart with a good portfolio, and spoke well during the interview. I put off a complete day to talk with him about everything that we do, tools we use, our process, file, organization. He’s proactive, asking questions and taking notes, which made me think, finally, a good candidate amongst them.

“Next day, he called me over to his desk, and he asked me something about where we keep docs, which I clearly had explained to him yesterday. Are you kidding me? It took him just a day to forget that, and it’s not just him, because someone who’s been here a month still sends email to the wrong person, and there’s many cases like that. My business partner says we need better documentation, but when I’m answering the same question on repeat, being behind on client work, and starting to get sharp with people who are just trying to learn, I know this is an investment and that after six months, they’ll be solid. But right now, this is very time consuming, and I’m not sure it’s worth it. Is this just what having employees is like? Please tell me I’m not the only one losing my mind.”

David Barnett:

Yeah, I can answer this. He’s investing in the wrong place. Because every business has systems. The problem with his business is that the systems are in his head, and he hasn’t properly documented how they do things. And he doesn’t have some kind of playbook or company wiki, or—you know, these things go by different names.

But you should be able to sit down with a new person and say: Here is the flow of how we handle a client file, or how we manufacture our widget, or whatever it is the business does. We go through these various steps. And here are the different people in our organization, and here are the job descriptions and the roles that they cover. And here are the tools that everybody uses. And this is your role, and this is the stuff you’re going to be doing. And here are the tools that we have established for doing those roles. And it’s all right here, because nobody can drink from the fire hose in one day and learn everything about a business and expect to have it top of mind.

There’s always going to be that need to refer. “But where did they say they did this? Where’d they say they did that?” And if, instead of spending a day trying to teach someone everything, you show them how to use your documentation so that they can find what they need on their own, or know what other people in the company are doing the same tasks, maybe they can go talk to their colleague instead of the boss, right? That’s what’s missing in this organization.

Kate Morgan:

Yeah, I would agree 100 percent. For my team, we are so well-documented. I love it because I have my own specific track that I train new employees in, but then I can push it off to everybody else, so I don’t have to deal with people. Because I’m not the most patient person.

Jay Goltz:

I think that is incredibly valuable and right. There’s another piece of this, I wonder, though, which is: In addition, did he check their references? Where did they come from? Maybe they were just fired from their third job because they can’t remember how to do it. I don’t know.

Loren Feldman:

It’s interesting to me that he said he thinks they’ll be solid in six months, which suggests that maybe he did hire the right person.

Jay Goltz:

Why does that make you think he hired the right person?

Loren Feldman:

He thinks they’re going to be good down the road.

Jay Goltz:

Maybe he’s wrong. I get it. I get it.

Loren Feldman:

He’s frustrated that they’re not picking it all up right away, as Dave said, despite not having the processes in place.

Jay Goltz:

But he emphasized that he spent the whole day with them. And my argument is: That’s part of the process. The other part is to find out: Why did they leave their last job? He didn’t mention they got great references. I didn’t hear that part of it. So I don’t know that that isn’t part of the problem.

David Barnett:

There’s two ways to learn a story, right? You either read it in a book, and you can refer to the book, or you have someone repeat the story to you several times. Or you watch the movie several times and you learn it through osmosis. And if you don’t have the proper documentation in place for someone to refer to, then the only option is education through osmosis and folklore. And that takes time, and he recognizes that. He’s saying: In six months’ time, this person will finally be able to regurgitate what I tell him after I tell it to him another 30 times. It just takes a lot of effort.

Kate Morgan:

And I was gonna say, Dave, in your business, I mean, you must see this. That was part of the value when I was looking to sell my company, was just how well documented it was, so they could just plug in new people without having to have me. And when I was at that point going to sell my company, I was only working on my business five hours a week because I had it so well-documented. But yeah, hiring, you have to have the right person as well.

Loren Feldman:

All right, my thanks to David Barnett, Kate Morgan, and Jay Goltz. As always, thank you guys for sharing. I really appreciate it.